![]()

RESPONSES TO: ANDERSON, FUKUYAMA, AND SEVIG

Toward Multicultural Competencies for Pastoral/Spiritual Care Providers in Clinical Settings: Response to Anderson, Fukuyama, and Sevig

K. Samuel Lee, PhD

KEYWORDS. Multicultural chaplaincy, religion, spirituality

A “multicultural revolution” that challenges the traditional health care delivery system (Sue, Bingham, Porché-Burke, and Vasquez, 1999) has been taking place in the United States in recent decades. In response, a number of organizations related to health care delivery developed guidelines for multicultural competencies to better serve the increasingly diverse U.S. population (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2003; National Association of Social Workers, 2001; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). Various organizations of health care chaplaincy, too, have been responding by considering multicultural competencies for their organizations. The Association for Clinical Pastoral Education (ACPE) created the Multicultural Competencies Task Force in 2001, and the task force has been working on a proposal to include multicultural competencies in the ACPE’s training and operation manuals. The Journal of Supervision and Training in Ministry published a special symposium on the topic of multicultural pastoral practice in clinical settings (DeVelder, Lee, and Griesel, 2002). This issue of the Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy is another example of how organizations related to health care chaplaincy are responding to the multicultural revolution in the United States.

As a result of a multicultural revolution in the U.S. that encompasses increased religious diversity, many chaplains have seen the need to change the name of their departments from “pastoral care” to “spiritual care.” This is in recognition that “pastoral care” is distinctively Christian and excludes care provided by and for non-Christians. Despite the debate about the new terminology that will undoubtedly continue (e.g., Miller, Lawrence, and Powell, 2003), the need to study “spirituality” in the psychological practices has been widely recognized and has resulted in many publications by psychologists since the 1990s. Such a change is expected to impact the fields of pastoral care, pastoral theology, and the ways seminary professors conceive of these traditional fields.

Elena Cohen (1999) of the Center for Child Health and Mental Health Policy enumerates the reasons for multicultural competencies in health care practices. They are (1) “to respond to current and projected demographic changes in the United States,” (2) “to eliminate long-standing disparities in the health status of people of diverse racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds,” (3) “to meet legislative, regulatory, and accreditation mandates,” and (4) “to gain a competitive edge in the market place.” In addition to Cohen’s rationale, pastoral or spiritual care providers must cultivate theological understanding that is born out of their religious tradition because what sets pastoral or spiritual practice apart from other clinical and psychological practices is that very theological identity. Adoption of multicultural competencies that promote attitudinal-cognitive-behavioral learning must be complemented by theological rationale to serve pastoral practitioners adequately in the long run.

Considering a theological foundation in multicultural pastoral practice portends enormous challenge. It does so because constructs used in theology and psychology are categorically distinct, although they may share common features. For example, when a psychologist (e.g., Steinberg, 1986) considers the meaning of love between couples, he sees a triangle of love that consists of passion, intimacy, and commitment and evolves through the life span. When a feminist pastoral theologian (Miller-McLemore, at press) considers the meaning of love between couples, she sees two sides of a coin held in tension between mutuality and self-giving. Also consider Fukuyama and Sevig’s comparing of spiritual and multicultural values. I wonder whether we can really “compare” the so-called spiritual values of “grace, intimacy, creativity” to the so-called multicultural values of “commitment and humor”? Such comparison, in my opinion, results in unnecessary and unfruitful syncretism of psychology and theology that ignores the distinctiveness and integrity of both disciplines.

Undoubtedly, much work must be done to explain the interplay between psychology and theology. To that end, Joann Wolski Conn (1985) examines the differential underlying premises, though somewhat reductionistically, of theology and psychology by contrasting Christian spirituality and psychological maturity. She shows various ways that theology and psychology may (or may not) come together. She proposes that both theology and psychology must learn from each other to more fully construct human experience.

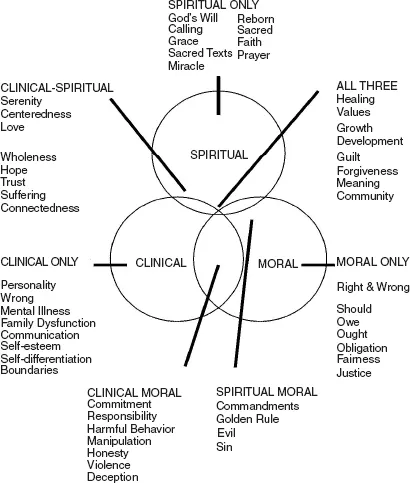

In a more specific way, William Doherty (1999) recognizes that there are “three domains of language and meaning” in clinical practice, including the domains of “the clinical world of mental health, the moral realm of obligations, and the spiritual realm of transcendent meaning.” He compares these three domains to Don Browning’s (1987) “ultimate metaphors (theology), obligation (ethics), and psychology,” which Browning considers to be categorically distinct. These domains overlap each other but must remain distinct “for purposes of clarity” as well as their own integrity. Perhaps more helpful than Fukuyama and Sevig’s comparison of spiritual and multicultural values, Doherty’s model presents three domains of language and meaning as described in Figure 1.

If Browning and Doherty are correct in assuming that the three domains described in Figure 1 are categorically distinct, what are the implications for developing multicultural competencies in pastoral or spiritual practice in clinical settings? I propose that three domains of language and meaning be seriously considered: theological, ethical, and clinical. Because most multicultural competency guidelines address the ethical and clinical domains, I shall limit myself in providing some examples of what I consider the essential theological issues.

In cultivating multicultural chaplains who are theologically grounded, we need to consider the call to serve the culturally different (cf. Jonah in Nineveh, the Good Samaritan story, Jesus’ ministry with the Syro-Phoenician woman or the woman at Jacob’s Well). The traditional religious understanding of the call, in my opinion, is better than Fukuyama and Sevig’s term such as “passion.” Theological consideration should also include the chaplain’s ability to engage in multicultural hermeneutics of texts that are considered authoritative within his or her religious tradition. This recognizes that often the multicultural context in which the chaplain finds himself or herself shapes how the text is to be read. For example, in considering that the event of Exodus is not exclusively for the slave Jews in Egypt, Brueggemann (1998) considers the meaning of “Exodus in the plural” in the Hebrew scripture. Brueggemann illustrates how a multiculturally competent biblical scholar should read the Hebrew scripture to be inclusive of God’s salvation. If, however, the chaplain is lost within his or her own ethnocentric theological perspective or worldview and cannot consider the local context (Schreiter, 1985) of patients, his or her hermeneutics may result in dogmatic imposition, cultural imperialism, or cultural violence. The ability to engage in interreligious dialogue is another component that should be included in the theological consideration of multicultural competencies. All in all, the basic theological foundation of multicultural competencies must show how who we are theologically shapes what we do as pastoral or spiritual care providers in clinical settings.

FIGURE 1. Three Domains of Language and Meaning

Note: Figure 1 adapted from: Dougherty, p. 185.

The cultural and religious diversity addressed by Fukuyama and Sevig and by Anderson in this volume clearly points to the urgency to develop multicultural competencies to better serve the culturally diverse clientele. Consequently, their emphasis is naturally placed on the chaplain-in-practice who is faced with the culturally different client. Multicultural competencies, however, must be reflected in all aspects of health care chaplaincy, not only in service delivery but also in recruitment and teaching of chaplains-to-be as well as in the ways training centers do their business. This point has been widely advocated (Sue et al., 1999; also see Sue et al., 1998).

A glimpse of cultural diversity among chaplain trainees can be seen in a snapshot survey of CPE students done by the ACPE during the summer of 2002. There were 2,050 CPE students during the summer of 2002, out of which 528 students returned the survey. My analyses of the data showed a tremendous range of diversity among them. Students were evenly divided by sex (52.3% female and 47.7% male). Students’ ages ranged from 22 to 65 years. At least 48 denominations were represented, including Judaism and Buddhism. Twelve persons reported some physical and mental handicapping conditions. Out of 112 ethnic minority students, 5.5 percent were African American, 0.6 percent described themselves as Asian American, 2.1 percent were Hispanic American, 0.8 percent reported being Native American, and 9.7 percent were international students. International students came from Australia, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, China, Columbia, India, England, Ethiopia, Germany, Haiti, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Korea, Mexico, Myanmar, Netherlands, Nigeria, Norway, Palestine, Peru, Philippines, South Africa, Taiwan, Tanzania, Uganda, Uruguay, Venezuela, Vietnam, and Zambia.

The cultural diversity that CPE students bring to their training sites is mind-boggling. In view of this diversity of chaplains-to-be, one cannot help but ask: Who is training this diverse group of chaplains-to-be today? This is a poignant question when we consider that today’s health care chaplaincy organizations predominantly consist of European American chaplains. Multicultural competency guidelines, therefore, must address how clinical centers can become multiculturally transformed and how they can help their predominantly European American chaplain trainers become more multiculturally competent. Such consideration points to the necessity to include in these guidelines how the training centers can recruit more culturally different chaplains so that the centers may more closely reflect the one-third of the U.S. population that are non-white European Americans. Clearly, we have a long way to go, but it is a worthwhile journey to take because, in becoming multicultural, we will all learn a lot more about who we are and who we can become.

AUTHOR NOTE

K. Samuel Lee is Visiting Assistant Professor of Pastoral Care and Counseling at Yale University Divinity School. His research interests focus on multicultural pastoral care, counseling, and pastoral theology. He has written numerous articles on multicultural theological education and multicultural competencies in clinical pastoral practice, and has contributed articles on the Korean American Church. He is an ordained minister in the United Methodist Church. From 1995 to 2002 he served as the Associate Dean and Assistant Professor of Pastoral Care and Theology at Wesley Theological Seminary. He is currently the Steering Committee Chairperson of the Society for Pastoral Theology and a member of the Multicultural Competencies Task Force of the Association of Clinical Pastoral Education. He received his MDiv from Yale University and PhD in counseling psychology from Arizona State University.

REFERENCES

American Psychological Association. (2003). Guidelines on multicultural education, training, research, practice, and organizational change for psychologists. American Psychologist, 58(5), 377-402. Also available at http://www.apa.org/pi/multiculturalguidelines.pdf.

Browning, D. (1987). Religious thought and the modern psychologies. Philadelphia Fortress Press.

Brueggemann, W. (1998). “Exodus” in the plural (Amos 9:7). In Brueggemann, W., & Stroup, G. (Eds.) Many voices one God: Being faithful in a pluralistic world, (pp. 15-34). Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

Cohen, E. (1999). Policy brief 1: National Center for Cultural Competency, winter 1999, Georgetown University Child Development Center, pp. 2-7.

Conn, J.W. (1985). Spirituality and personal maturity. In Wicks, R., Parsons, R., & Capps, D. (Eds.) Clinical handbook of pastoral counseling volume 1 expanded edition, (pp. 37-57). NY: Integration Books.

DeVelder, J. Lee, K.S., & Griesel, A. (Eds.) (2002). Symposium: Multiculturality in the student-supervisor/teacher relationship. Journal of Supervision and Training in Ministry. 22.

Doherty, W. (1999). Morality and spirituality in therapy. In Walsh, F. (Ed.) Spiritual resources in family therapy (pp. 179-192). NY: Guilford Press.

Miller, R., Lawrence, R., & Powell, R. (2003). Guest editorial. Journal of Pastoral Care and Counseling, 57(2), 111-116.

Miller-McLemore, B. (2003 at press). Sloppy mutuality: Love and justice for children and adults. In Anderson, H., Miller-McLemore, B., Foley, E., & Schreiter, R. (Eds.), Mutuality Matters: The Promise and Peril of Democratic Families. Chicago: Sheed&Ward.

National Association of Social Workers. (2001). NASW standards for cultural competency in social work practice (brochure). NASW Press.

Schreiter, R. (1997). Constructing local theologies. NY: Orbis Books.

Sternberg R. (1986). A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review, 93, 119-135.

Sue, D.W., Bingham, R. P, Porché-Burke, L., & Vasquez, M. (1999). The diversification of psychology: A multicultural revolution. American Psychologist, 54(12), 1061-1069.

Sue, D.W., Carter, R.T., Casas, J. M., Fouad, N.A., Ivey, A.E., Jensen, M., LaFromboise, T., Manese, J.E., Ponterotto, J.G., & Vazquez-Nutall, E. (1998). Multicultural counseling competencies: Individual and organizational development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (March, 2001). National standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health care: Final report.

K. Samuel Lee, PhD, is Visiting Professor of Pastoral Care and Counseling, Yale Divinity School, New Haven, CT (E-mail:

[email protected]).

[Haworth co-indexing entry note]: “Toward Multicultural Competencies for Pastoral/Spiritual Care Providers in Clinical Settings: Response to Anderson, Fukuyama, and Sevig.” Lee, K. Samuel. Co-published simultaneously in

Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy (The Haworth Pastoral Press, an imprint of The Haworth Press, Inc.) Vol. 13, No. 2, 2004, pp. 43-50; and:

Ministry in the Spiritual and Cultural Diversity of Health Care: Increasing the Competency of Chaplains (ed: Robert G. Anderson, and Mary A. Fukuyama) The Haworth Pastoral Press, an imprint ofThe Haworth Press, Inc., 2004, pp. 43-50. Single or multiple copies of this article are available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service [1-800-HAWORTH, 9:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. (EST). E-mail address:

[email protected]].

![]()

Forging Spiritual and Cultural Competency in Spiritual Care-Givers: A Response to Fukuyama and Sevig and Anderson

Marsha Wiggins Frame, PhD

KEYWORDS. Multicultural chaplaincy, religion, spirituality

In their articles, Anderson and then Fukuyama and Sevig make convincing cases for the need for health care chaplains to become competent in spiritual and cultural diversity. As a United Methodist clergywoman for nearly 30 years, and as a counselor educator for the past 10 years, I applaud the intersection of spiritual and cultural diversity with pastoral care.

Anderson’s five dimensions of spiritual and cultural competency are a useful beginning for the journey toward chaplains being equipped to provide pastoral care to a variety of persons from a wide range of religious, spiritual, and cultural contexts. The cases he provides illustrate well the complex web in which chaplains often find themselves.

Fukuyama and Sevig are accurate when they speak of spirituality and religion being embedded in culture, and in their careful descriptions of cultural diversity and delineation of the distinctions between religion and spirituality. The themes in their article parallel closely my own work (Frame, 2003). In response to Anderson’s steps and Fukuyama and Sevig’s key points on the journey, I offer specific strategies and tools that may assist chaplains in acquiring spiritual and cultural competency.

SELF-AWARENESS

One of the strengths of clinical pastoral education (CPE) is experiential learning with its ...