![]()

1 | Communication difficulties |

Identifying the specific nature of a communication problem

Speech and language is one of the most difficult areas of the curriculum to assess. This is because it depends very much on the situation, the individual child, their background and experience. It is often hard to know what you should be looking for and how far from ‘normal’ the child’s speech is.

Verbal communication involves two main components:

Speech, the mechanical aspect of communication, is the physical ability to produce the sounds, words and phrases. Articulation is the term used for the motor process of speech production. It is the accurate and precise movement and coordination of the organs of articulation (e.g. tongue, jaw, teeth, lips) to produce sounds. Phonology is the organisation of those speech sounds to form words and phrases.

Language is the understanding of concepts and the way sound patterns, words and phrases relate to one another to carry meaning and information. The acquisition of vocabulary and grammatical structure are part of the process of language development.

There are many influences on the child’s developing expressive (output) and receptive (understanding) skills. These may enhance or suppress the development of speech and language, depending on the quality of the child’s sensory and physical functions. The development of communication relies on the child’s ability to take in sensory information, to process that information and to become competent at using the organs and muscles that are necessary to produce speech. It is also dependent on the range of stimulation provided and the experiences offered in the formative years prior to school entry. The developing child may experience difficulties in one or more areas of communication and even a short-term problem, such as an ear infection, may influence the way that a child perceives certain sounds as they are learning them.

A preschool child may have inaccurate articulation or ‘babyish’ language structure and other developmental milestones may have been delayed (e.g. crawling, sitting, walking …). At school entry, some of these immaturities may persist.

In many cases, children with poor communication skills at preschool or school entry will rapidly show improvements when placed in the structured environment of a nursery or reception class. The influences of their peer group, the need to communicate and the wealth of everyday language activities all provide motivation and stimulation for the development of speech and language.

In some cases, however, the difficulties may persist. There could be specific reasons for the delay in developing speech and language skills and these will need to be monitored and investigated (see Chapter 8 – Specific speech and language disorders).

Action

If the child does not make the expected progress within the first few weeks, or if there appears to be a more severe difficulty which is making it hard for the child to participate fully in the class activities and/or social or play situations, then the child’s speech should be investigated further.

1. Discuss your concerns with the parent (they may be equally concerned or may not have noticed a problem, but their input is vital and a legal requirement).

2. Check whether the child’s hearing has been tested.

3. Check if there has been any previous involvement with a speech and language therapist (this information is not always passed on by parents at school entry).

4. Discuss your concerns with other involved members of staff, including the special educational needs coordinator (SENCO) and the head teacher.

5. Following observation, the SENCO may decide to place the child at School Action level of the special educational needs (SEN) register and draw up an Individual Education Plan (IEP). This will indicate areas needing specific observation, strategies for helping the child and details of any in-class support or differentiation that may be required.

Once a problem has been identified, the teacher needs to initiate a process of observation and evaluation of the child’s communication skills so that a clearer picture of the specific areas of difficulty, progress or deterioration, environmental influences etc. can be monitored and assessed.

The SENCO, the class teacher or teaching assistant, can carry out observation. Results of observation should be used to inform the planning of a programme of support or intervention.

As a general approach, I would suggest:

• set aside specific times for observation;

• draw up a rota or list of children to be observed;

• choose a selection of activities for observation (interaction with another child, play house activities, structured play activities, sharing a book, participation during circle time or literacy hour class/group activity);

• observation sheets or a diary should be at hand for use during selected times and also for any impromptu moments when it might be important to jot down a relevant comment.

The whole range of activities that take place in the nursery/school classroom, playground or any other part of the school can provide opportunities for informal assessment and observation. Children need to be observed in a range of situations, in different social groupings (pairs, friendship groups, activity groups etc.) and curriculum areas (sharing books, sand and water play, areas set up for observation, e.g. fish tank, pets, display corner, science investigations, working out a practical number problem etc.). You may also find it valuable to observe the child interacting with a parent, brothers or sisters, as speech may be more spontaneous and relaxed in a familiar situation. This could be set up at school or could involve a home visit.

Communication is one of the areas where it is easy to make a ‘wrong’ or unfair assessment. Be aware that a shy child may take time to feel comfortable with a group of other children or with unfamiliar adults, that a child may revert to ‘baby’ talk when feeling insecure and that some children find it difficult to respond to direct questioning in an unfamiliar situation.

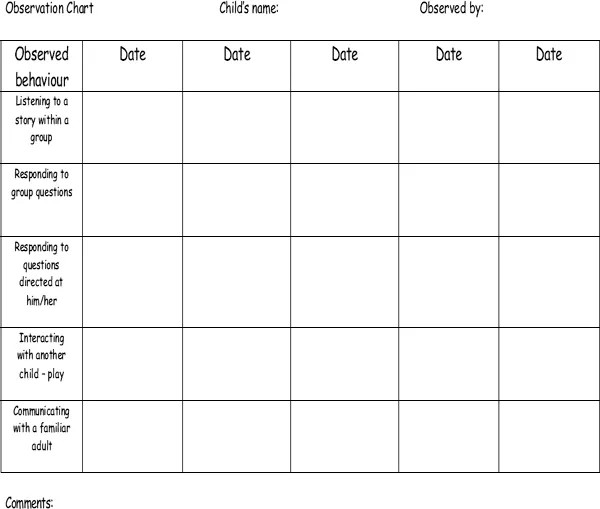

You may choose to use the observation chart and articulation record provided (Figure 1.1), or use one of your own devising. I would suggest that you include the following areas to give a thorough and broad investigation:

General abilities

• Group participation

• Social interaction with peers

• Listening and responding to stories

• Describing and relating real and imaginary events

• Giving and responding to instructions

• Asking and answering questions

• Communication with family members

Specific abilities

• Articulation/phonology (details of wrongly articulated sounds, whether initial, medial, final, vowel/consonant, consistent or random substitutions etc.) – see Chapter 3

• Difficulty repeating/learning new sounds or words

• Imitation of tongue movements

• Use of vocabulary

• Sentence formation (specify any immature or incorrect structures)

• Ability to communicate needs

• Reluctance to communicate

• Use of any alternative means of communication, i.e. pointing, gesture, signing, taking an adult to show them etc.

Figure 1.1 Observation chart. © Gill Thompson (2003) Supporting Communication Disorders, David Fulton Publishers.

When a profile of the child’s communication abilities has been achieved, it will be necessary to establish whether this is a problem that can be dealt with in school, with the support of the parents or whether it is going to necessitate a referral to a speech and language therapist.

If the child has significant communication difficulties which are preventing full participation in class activities and improvement has not been apparent in spite of support and encouragement in the classroom, then it will be advisable to seek a professional opinion.

Guidance for referral to speech and language therapy

Action

Once a referral is made and an outside professional becomes involved, the child needs to be placed at School Action Plus of the SEN register. This indicates that advice has been sought from an outside agency and that the therapist is contributing to the IEP.

The following are of note regarding the referral process.

• The parents will need to be informed and their cooperation should be sought (this is not always forthcoming but if it is, it can make all the difference).

• I have found that the best way to make a referral is to ask the child’s parents/carers to speak to their general practitioner (GP) and request that the child has a hearing test and is seen by the speech and language therapist. It is also possible for the school or parents to refer directly. Whichever referral route you choose, it is helpful to send information regarding your concerns and the nature of the support already provided at school. Copies of any assessments you have done and a brief summary of the child’s difficulties give a clearer picture to the therapist in the initial stages of referral.

• There are usually waiting lists, so be prepared to provide a programme of support at school while you wait for the child to be seen (see suggestions for general activities – Chapter 4).

• When the child is given an appointment, contact the speech and language therapist and introduce yourself (letter or phone) and explain that you would like advice on how to work with the child at school and some suggestions for support. Parental permission will need to be given before the speech and language therapist can disclose this type of information. It is a good idea to start this link early so that the therapist can get permission from the parents when they take the child to the initial visit.

• Offer to send the therapist details of your own observations and support work so that it is clear what has been done already.

• Suggest a home/clinic/school book so that any weekly work can be supported at school and incorporated into the IEP/weekly planning.

The child is likely to be seen for a block of approximately six weeks and then given a break. Make sure that you have information for making your own programme of work at school once the therapy period is completed. A decision should be made as to whether the class teacher or the SENCO will liaise directly with the therapist and be the school contact. This avoids any misunderstandings and creates a good channel for communication.

Speech and language therapy is generally the responsibility of the NHS (National Health Service) and children with identified needs will be seen by the speech and language service provided by the local NHS Trust.

In the SEN Toolkit (DfES 2001a) the following recommendations are made:

Wherever possible, therapy for children attending school should be carried out collaboratively within the school context. In some cases, children may need regular and continuing help from a speech therapist, either individually or in a group. In other cases, it may be appropriate for staff at the child’s school to deliver a regular and discrete programme of intervention...