- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

APL: Equal Opportunities for All?

About this book

Here, the authors explore practical ways of implementing APL for the benefit of individuals, employers and the community as a whole, showing how it can make a real contribution to equality of opportunity.

Chapters look at the particular needs of various sectors of the community, and how APL can be used to meet those needs. For ethnic communities, those whose first language is not English, and those who arrive in Britain with qualifications from overseas, the APL process can be a vital stage in the search for education, employment and equality of experience. People with disabilities find that APL can help break through barriers and offer new breadth of opportunity, whilst for women it can lead to greater recognition and improved career progression. Through the use of case studies and practical examples the authors offer detailed guidance on methods of implementation, staff development and continuing support to help tutors, managers and senior staff make effective use of APL.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

WHAT IS APL?

APL, or Accreditation of Prior Learning, is the process of identifying, assessing and accrediting a person’s competences, knowledge and skills, however they have been acquired. Where this concerns uncertificated learning it is known as the Assessment of Prior Experiential Learning (APEL) and is a subset of APL. It constitutes, essentially, a formal recognition of the fact that people learn many things and acquire many skills outside the formal structures of education and training.

The process that individuals go through for the purposes of APL is in itself of value in helping them to analyse and assess their previous experience, and develop a sense of individual worth and growth. It serves as an opportunity to explore learning and career needs and work out future directions. It may also lead to formal recognition of achievement in the form of National Qualifications, promotion for people who are already in work, acceptance on courses in higher education and sometimes credit towards other qualifications.

For employers APL offers the opportunity of recognising the skills and abilities of their employees for the purposes of promotion, identifying further training needs, and improving the utilisation of human resources.

For educational establishments, APL provides a means of matching provision much more closely to demand, and of attracting a broader spectrum of students who can start the educational process from the point most appropriate to them and achieve their aims by the most direct route.

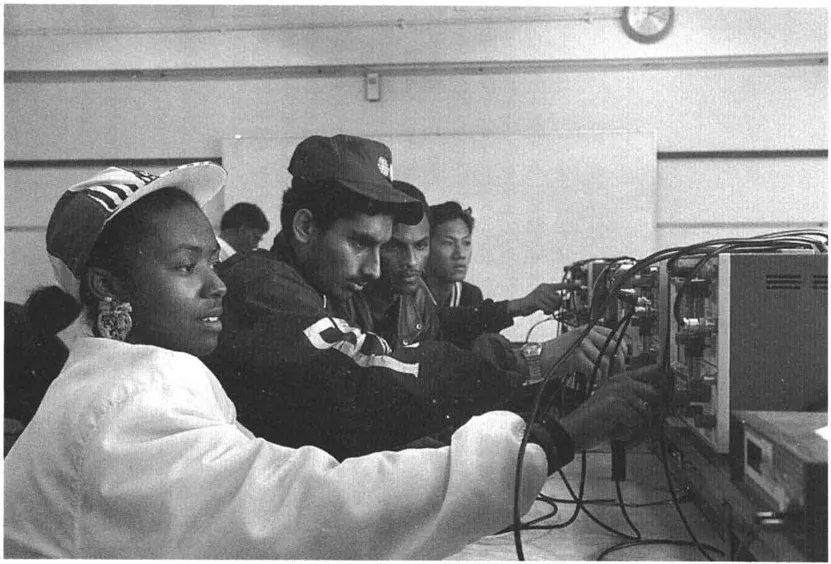

© Lenny Peters

Why Apl?

In the European context, with only one in three workers in Britain holding a vocational qualification compared to 64 per cent and 40 per cent of the workforce respectively in Germany and France, for example, the need for assessment and accreditation both for those in work and those seeking employment is pressing.

The government currently spends over £2 billion on education and training for adults, soon to become the responsibility of the Further Education Council. Nearly two million students study in further education colleges, about 80 per cent of them part time. The 1991 White Paper Education and Training for the 21st Century emphasises the importance of good quality education for adults ‘to help them improve their qualifications, update their skills and seek advancement in their present career or in a new career’. APL is an important means of attaining this goal

Apl for the whole community

It is the aim of this volume to demonstrate ways in which APL can be implemented in order to offer greater opportunities for self-realisation to individuals from all sectors of the community, to improve the service offered to those seeking education and training, and to increase the overall numbers of people with recognised qualifications. The prime objective of APL is to broaden the range of those participating, and increase recognition of the different types of experience people have to offer.

In order to do this, we shall be looking at the different sectors of the population in terms of what qualifications they have, what types of employment they are involved in, the levels and areas of unemployment and who is affected. We shall be questioning the lack of recognition of skills and experience in particular sections of the population, and looking at ways of improving assessment and accreditation of competence for them.

The following facts and figures are drawn from Social Trends, a publication of the Government Statistical Service (Central Statistical Office 1992), in order to give an indication of areas where APL can have a particularly useful function, as a preamble to examining in detail the equal opportunities implications.

Qualifications

Since the introduction of GCSEs in 1988 the proportion of pupils leaving school with no graded examination result has fallen to 9 per cent of boys and 7 per cent of girls. However, the proportion of 16- to 18-year-olds participating in education and training in the UK, at 69 per cent, is one of the lowest in the European Community, with only Italy and Spain coming off worse. Looking solely at 16 year olds, the UK had the lowest full-time participation rate (only 50 per cent) in 1988. So for a large proportion of young people, education ends at 16, at least temporarily, and they join the labour force, with few or no qualifications.

As far as the total population of working age is concerned, in 1992, 29 per cent of men and 36 per cent of women had no qualification at all. Figures for different ethnic groups show a greater proportion of both men and women from Pakistan and Bangladesh having no qualification, with the figure for men being 52 per cent and that for women 68 per cent.

Parents’ socio-economic group also has a significant bearing on the level of qualification of their children, with 54 per cent of the children of unskilled manual workers being unqualified, 47 per cent of the children of semi-skilled workers and 37 per cent of those of skilled manual workers. These figures give us a picture of a significant proportion of the adult population whose skills and experience are going unrecognised and who could benefit from APL as a means towards qualifications.

Immigrants and asylum seekers

In the last half of the 1980s about 47,000 people were accepted for settlement in the UK, of which nearly half came from Asia, and another 16 per cent from Africa. In addition, between 1989 and 1991 the number of applications for asylum increased dramatically, with 57,000 in 1991, or one per thousand of the population, compared to 22,000 in 1990 and 10,000 in 1989. These new arrivals to the country bring with them a wealth of experience and often high-level qualifications from their country of origin or another country. Recognition of their existing skills through APL, together with advice and counselling, is essential, if they are to reorientate themselves towards building a new life and career in this country.

Employment

The labour force is undergoing changes which have significant implications for education and training, and call for flexible approaches. Between 1971 and 1990 the number of women in the labour force rose by three million, while the number of men rose by only 300,000. This trend is projected to continue to the extent that by the turn of the century women will make up 45 per cent of the total civilian labour force. The increase in the number of women working outside the home is partly due to an increase in the availability of part-time jobs but also relates to demographic factors such as comparatively low birth rates and a rise in the average age at which women have children. Women in the Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities, however, show a different trend, with only 24 per cent involved in economic activity outside the home. Women in all socio-economic and ethnic groups tend to stay out of employment while their children are very young, with 57 per cent of all mothers of under 5-year-olds not working outside the home, whereas 72 per cent of women with no dependent children are in employment.

At the same time the number of young people in the labour force is falling and is projected to continue to fall by a further 800,000 by the year 2001. The changing age structure of the labour force presents recruitment problems for employers. Those employers who rely on young people as a significant source of employees face declining numbers until the mid-1990s. They therefore need to make better use of alternative recruitment sources, such as the unemployed, women returners to the labour market and older workers.

Part-time employment

Of those who worked part time in 1990, 86 per cent were women. Many people work part time because they want to. Only 6 per cent, in the 1990 figures, worked part time because they could not find a full-time job. However, part-time workers frequently experience fewer benefits from training and development programmes at work and have poorer chances of promotion. APL offers opportunities for part timers to gain recognition of their achievements and extend their skills.

People with disabilities

Among those who work part time by choice, 2 per cent do so because they are ill or disabled. Of the six and a quarter million disabled people in Britain nearly 200,000 are currently pupils in hospital schools, special schools or other public sector schools. These young people preparing to enter the labour force, and those who are already working full time or part time, or who are unemployed, may have skills and abilities which are not recognised by traditional qualifications. Discrimination through attitudes to disabled people or through environmental barriers may have hindered their access to education and training, yet they may have acquired valuable skills and experience. APEL has a role to play in ensuring that those skills are recognised.

Self-employment

Self-employment has increased dramatically over the last decade.

After changing little during the 1970s, the number of self-employed people increased by 57 per cent between 1981 and 1990, with almost half of them working in the construction sector or the distribution, catering and repairs sectors of the economy. Many people who are self-employed do not have formal qualifications, yet the skill and expertise they build up is considerable. APEL provides a means of quantifying and building on those skills.

After changing little during the 1970s, the number of self-employed people increased by 57 per cent between 1981 and 1990, with almost half of them working in the construction sector or the distribution, catering and repairs sectors of the economy. Many people who are self-employed do not have formal qualifications, yet the skill and expertise they build up is considerable. APEL provides a means of quantifying and building on those skills.

Unemployment

The number of unemployed (using the claimant count) rose above two million in 1991 with unemployment rates being highest among the young, particularly those under 20. The Labour Force Survey, which is a household survey, gives an estimate a quarter higher than the claimant count, part of which would be accounted for by the fact that most married women stop signing on after one year of unemployment, because their entitlement to benefit comes to an end if their husband is working or claiming.

Some factors that influence unemployment duration are race, disability, age and previous occupation. Unemployment rates are higher among other ethnic groups than among white people, particularly for Pakistani and Bangladeshi men and women and West Indian men, although the rate of unemployment is also falling more rapidly for those groups. According to Colin Barnes, research worker for the British Council of Organisations of Disabled People ‘they (disabled people) are three times more likely to be out of work than their non-disabled counterparts, and three times more likely to be out of work for long periods’ (Barnes 1992). The length of unemployment for all groups also increases with age, with 28 per cent of unemployed men aged between 50 and 59 having been unemployed for more than three years. Looking at previous occupation, in 1990, 41 per cent of unemployed people had previously been employed in manual occupations. There is also an apparent mismatch between the skills of unemployed people and those required by employers, coupled with problems in how unemployed people obtain information about jobs and apply for them. APL clearly has an important role to play in assessing the skills of unemployed people, accrediting them and enabling them to build on those skills as a means of entering an appropriate and satisfying occupation.

In terms of social trends, then, we are looking at a substantial level of unemployment, particularly amongst young people, certain ethnic groups and women. At the same time employers are having to rethink recruiting targets and prepare to take on a workforce of a different nature, including more older people and more women. Other important groups to consider in terms of skills and training are part-time workers (predominantly women), people with disabilities, self-employed people, and new arrivals to the country.

EQUALITY OF OPPORTUNITY

In the subsequent chapters of this book, we are going to focus on some of the groups mentioned above, to examine in greater detail how APEL can be implemented for the benefit of individuals, employers and the community as a whole. We will first of all look at issues relating to equality of opportunity. Legislation to prevent discrimination on racial grounds has been on the statute book for some time, as well as legislation aimed against discrimination against women, although many would question the effectiveness of such legislation. A bill has been proposed to prohibit discrimination against disabled people but has not yet become law. Many organisations have equal opportunities policies and many employers call themselves ‘equal opportunity employers’.

Certainly not many educational establishments or companies would admit to any kind of discrimination in their recruitment methods. Yet the statistics clearly indicate that sections of the population are at a disadvantage, both in employment terms and in relation to education and training.

In Chapter 2 we will look at the aims of some of these policies, and how they are put into practice. We will examine the equal opportunities policies and statements of bodies such as the National Council for Vocational Qualifications (NCVQ) and City and Guilds and at how practical implementation of policies can be provided for, on the grounds that the point at which a policy has a genuine effect is when the resources are made available to put practical procedures into place. We will suggest that APL is one practical procedure which can contribute enormously to the real implementation of equality of opportunity. Finally we will give a brief outline of the APL process and look at some of the implications for access to higher education within the context of Credit Accumulation and Transfer Schemes (CATS).

The different ethnic communities

In Chapter 3 we will look at some of the different ethnic communities in Britain, with the aim of highlighting what particular education and training needs are not being met and what role APL could play in meeting them. We will look first at the Afro-Caribbean communities and what factors have led to them being disadvantaged in the education system, such as the failure to acknowledge the validity of their different cultural background, and to recognise the complex language situation of people of Caribbean heritage. We will then look at some of the communities where other languages are spoken, what difficulties members of those communities experience in the education system and the job market, what areas of work they are involved in and what talents and skills are going unrecognised or being under utilised.

Recognition of qualifications from overseas

The first stage for many new arrivals, whether they have come to this country specifically for education or training or whether they have come to build a new life, is to establish the status of the qualifications they already have. The recognition of equivalences between qualifications can save precious time and money spent on repeating studies already started or completed elsewhere. Even partial recognition can give valuable credits towards full accreditation. Chapter 4 will outline ways in which recognition of overseas quali...

Table of contents

- Cover page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword to Apl: Equal Opportunities for All?

- Foreword to the series

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Equality of opportunity and the Apl process

- Chapter 3: Apl and the Experience of Different Ethnic Communities in Britain

- Chapter 4: Recognition of qualifications and experience from overseas

- Chapter 5: Apl and Speakers of Other Languages and Dialects

- Chapter 6: People with disabilities

- Chapter 7: Apl and Women

- Chapter 8: Issues of class

- Chapter 9: Conclusion

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access APL: Equal Opportunities for All? by Cecilia McKelvey,Helen Peters in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.