- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reading and Learning Difficulties

About this book

First Published in 2005. All teachers recognise how crucial is the acquisition of good reading skills. This book will help teachers understand how pupils learn and will help them to meet those pupils' different needs through appropriate intervention. It includes: Clear explanation of different learning difficulties; Guidelines on types of assessment; Advice on how to select the best type of intervention and support. For teachers, TAs, Numeracy Co-ordinators and SENCOs.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

| 1 | Learning to read |

Learning to read and write is arguably the most complex task humans face. (Strickland 1999, p. xix)

It is clear that, for most children, the process of learning to read begins long before they enter school and receive instruction from teachers. Studies of preschool children indicate that if they live in a family environment where they observe adults or siblings using print materials and engaging in writing, they too will be motivated to engage in such activities. In literate home environments it is normal for stories to be read to children, and for them to be given books to own and explore. As a result, many quite young children begin to discover for themselves important concepts about reading and print (Adams 1990; Cunningham et al. 2000; Roberts 1999). Most young children will want to learn to read and write, and will soon begin to experiment with books and ‘pretend’ reading and writing. Their learning at this stage is mainly incidental, rather than the result of any formal or systematic teaching – although some wise parents intuitively engage their children in many types of informal teaching and learning interactions when reading and sharing books.

Researchers have referred to this early pre-reading stage as ‘emergent literacy’ (Burns, Griffin & Snow 1999; Foorman et al. 1997; Strickland 1990). Emergent literacy is defined by Sulzby (1991, p. 273) as, ‘The reading and writing behaviours of young children that precede and develop into conventional literacy’.

Emergent literacy

The period of emergent reading begins in the very early years of a child’s life and extends into the first years of schooling. For some children with learning difficulties, or with developmental delay, the emergent reading stage may even extend into the middle primary years. Fields and Spangler (2000, p. 104) have remarked that, ‘Schools would like it if all youngsters moved from emergent reading to independent reading during first grade, but it is totally unrealistic’.

The notion of emergent literacy, as a fairly natural developmental process, has largely replaced the earlier concept of ‘reading readiness’. The old notion of reading readiness implied that children could not begin to learn to read until their latent perceptual and cognitive abilities were mature enough to enable them to cope with the challenging task of reading (Cunningham et al. 2000). For many years the erroneous belief was held that a child must have a so-called ‘mental age’ of at least six years to be ready for reading. Such a belief has been discredited. The evidence is that many children learn to read in the preschool years (Adams, Treiman & Pressley 1998). A child’s readiness to learn to read has much more to do with his or her prior learning experiences and opportunities than with physiological or neurological maturation.

As part of the emergent stage, even very young children begin to understand that books contain stories and pictures, and they show interest in looking at and handling books. They come to realise that print on the page conveys meaning to those who can ‘read’ and that ‘readers’ can convert this print into spoken language. They may develop an awareness that a story begins at the ‘front’ of the book and that the reader processes the print from left to right across and down the page while reading a story. Through fairly frequent exposure to books and stories (and perhaps as a result of watching children’s educational television programs) some children begin to remember the shapes and names of letters of the alphabet, and may even begin to identify a few words. At the same time, they are learning to recognise commonly occurring signs, symbols and words encountered daily in their environment.

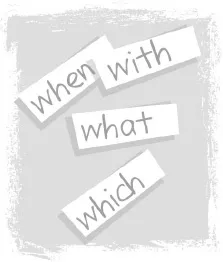

In terms of their auditory skills (phonological skills), many children are becoming aware that some spoken words rhyme and some words begin with the same sound. In their oral language they will often engage spontaneously in ‘word play’, creating rhymes or using alliteration. A few children will acquire a complete understanding that the words they say and hear can be ‘stretched out’ and said slowly so that each sound within the word can be heard (phonemic awareness). Many children, however, do not acquire phonemic awareness until specific teaching occurs when they enter kindergarten or school.

The pre-school children who are most advanced in their development, or who have had more direct guidance from someone as part of their exposure to books and print, begin to discover that there is a connection between the sounds in words and the symbols on the page of print (Barron 1994; Roberts 1999). In this respect, their early attempts to spell words as they pretend to write are extremely important. During the emergent spelling stage children attend more carefully to sounds within a word, and wonder how these sounds might be represented by letters.

Lyon (1998, p. 18) wrote:

The evidence suggests strongly that educators can foster reading development by providing kindergarten children with instruction that develops print concepts, familiarity with the purposes of reading and writing, age-appropriate vocabulary, language comprehension skills and familiarity with the language structure.

All this learning will, of course, be acquired more rapidly if an interested adult or sibling draws a child’s attention to words, letters, sounds, rhymes, directionality of print and the format of a book when a story is being read or when he or she experiments with writing (Cunningham 2000; Schumm & Schumm 1999). The positive interaction between a competent reader and a beginner is a crucial factor in determining just how much young children learn during the emergent reading stage.

To summarise, the experiences young children encounter during the emergent reading stage should, according to Schumm and Schumm (1999), result in the following acquisitions:

• Story awareness – recognising that a story typically has a beginning, middle and end; usually has characters, and that the events in the story occur in times and places.

• Book awareness – recognising the basic parts of a book (cover, title, pages); knowing where a reader begins to read a story; understanding page turning; and so on.

• Print awareness – understanding the difference between letters and words; recognising where text begins on the page; knowing the direction a reader’s eyes move when reading a line of print; gradually learning the names and common sounds (phonemes) associated with different letters.

• Phonological awareness – an understanding of words as separate units in speech (word concept); an ability to detect similarities and differences in speech sounds, and to detect alliteration and rhyme in speech; the ability to break spoken words down into separate sounds; the ability to blend sounds into words.

• Environmental print awareness – recognising signs, symbols and words that occur frequently in their environment (for example, street signs, product labels in stores or on television, name tags, logos).

Moving beyond the emergent stage

Much more will be said about print awareness and phonological awareness later but at this point it is essential to dispel a possible misconception. It must not be assumed that because many pre-school children in supportive family environments learn so much about reading without any systematic teaching, they will also become proficient readers without direct instruction in school. Such a notion, according to Foorman et al. (1997 p. 246), is ‘blatantly wrong’. While some children learn to read and write with remarkable ease even before commencing school, for the vast majority of children, proficient reading skills will not emerge naturally out of their oral and aural language experiences. In general, children do not learn to read by osmosis, they learn by being taught the necessary skills and strategies to identify words and make meaning from text (Adams, Treiman & Pressley 1998; Graves, Juel & Graves 1998; Lyon 1998; Turner 1995). They also require abundant opportunities to practise everything they learn.

Many children will not make a smooth transition from the emergent reading stage to independence in reading without a great deal of skilled teaching. This is particularly the case with children who come to school lacking awareness of stories, books, print and phonemes. Nicholson (1999) has summarised much of the research indicating that, if used alone, informal exposure to books and print will not ensure that all children acquire the knowledge and skills to become competent readers. Pre-school and early school exposure to books, and an opportunity to experiment with writing creates a very necessary, but not sufficient, condition to pave the way for independence in reading. High-quality instruction is also required.

The importance of phonological awareness

Children’s success in beginning reading is very highly correlated with their level of phonological awareness (Torgesen 2000; Tunmer & Chapman 1999). Phonological awareness is the general term used to describe an individual’s understanding of the sound features of language. It includes an awareness that language utterances are made up of individual words, that words themselves are made up of one or more syllables, and that a syllable is made up of separate units of sound (phonemes). The language children hear everyday is perceived mainly as a continuous flow of speech, not as a sequence of word-units separated by breaks, as in printed language. Young children do not necessarily understand that ‘words’ exist as units in their own right (McGuinness 1998). Asking some children to ‘look at the first word in the sentence’ can be a totally meaningless instruction if word concept is not established. For this reason, one very important aspect of a young child’s early development in phonological awareness is the acquisition of ‘word concept’ (Adams, Treiman & Pressley 1998). Until a child appreciates that a word is a unit of speech there is little relevance in attempting to talk to the child about ‘sounds within the word’ or to attempt to teach any basic sound-to-letter correspondences. Children do not seem to benefit much from instruction in letter–sound correspondences until they possess an adequate level of phonological awareness (Castle 1999).

Phonemic awareness is the specific term referring to that aspect of phonological awareness involving the recognition that a spoken word is made up of a sequence of individual sounds. Phonemic awareness has nothing to do directly with print; it is the metalinguistic ability that enables an individual to identify sounds within words. Children need to be trained from the start to become aware of the individual phonemes in words because this understanding makes it very much easier for them to learn to read. Without phonemic awareness children will not be able to identify and discriminate among the various speech sounds – an essential first step in learning phonics (Rubin 2000). Snow, Burns and Griffin (1998, p. 52) describe the situation clearly:

Because phonemes are the units of sound that are represented by the letters of the alphabet, an awareness of phonemes is the key to understanding the logic of the alphabetic principle and thus to the learnability of phonics and spelling.

Lack of phonemic awareness seems to be the start of a vicious cycle (Pressley 1998). Deficiencies in phonemic awareness undermine a child’s ability to learn how to decode words. Poor decoding skill results in slow and frustrating encounters with print. This, in turn, undermines the successful reading and comprehending of a wide range of text. The result is children who do not enjoy reading, have little inclination to persevere and, when compared with their peers, engage in much less practice.

Phonological skills and practice in reading are considered to share a reciprocal relationship. Success in beginning to read appears to depend on having already acquired some degree of phonemic awareness; then, as a child reads more material and encounters many new words, so facility in decoding and phonemic awareness increases (Moustafa 2000; Perfetti et al. 1987). Children who read very little miss out on this opportunity to improve.

Phonemic awareness in young children has proved to be a more potent predictor of later reading success than measures of intelligence, vocabulary or listening comprehension (Castle 1999). Lack of phonemic awareness has also been identified as a probable causal factor in many cases of reading disability (Stanovich 2000; Torgesen 2000). This issue is discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.

Phonemic awareness develops most naturally from the many and varied oral and aural language interactions that occur in the family and in the preschool or early school environment. In particular, children may well have acquired phonemic awareness without specific instruction if they have had many stories read to them, have listened to and recited rhymes, played games such as ‘I spy’ and attempted to spell words while pretending to write. Other children may have been less fortunate and will require direct teaching in order to establish this core concept (Nicholson 1999; Pressley 1998). Children from restricted language backgrounds are most at risk of failing to discover the phonological characteristics of their language.

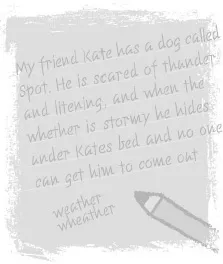

Examples of phonemic skill

The various aspects of phonemic awareness usually thought by researchers and educators to be important for reading development are:

• recognising rhyme (bat, fat, sat, hat, mice, dice, rice, price);

• identifying the initial sound in a word (house = /h/; tree = /tr/);

• being aware of al...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Preface

- 1 Learning to read

- 2 The reading process

- 3 Learning difficulties

- 4 General teaching approaches

- 5 Specific teaching methods and strategies

- 6 Teaching the basics: phonemic awareness, phonic skills and sight vocabulary

- 7 Assessment

- 8 Intervention and support

- Appendices

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Reading and Learning Difficulties by Peter Westwood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.