![]()

1

‘ALL THE ISLAND AND MANY OTHER ISLANDS ALSO’

THE ATLANTIS LEGEND

Plato’s story of Atlantis has the unenviable reputation of being the absurdest lie in all literature. One major problem has been the long eclipse which Plato’s reputation as a philosopher and political thinker suffered during the twentieth century. Some scholars have written about Plato in such vitriolic terms as to test the boundaries of the term ‘scholarship’. He has been damned for his assumed moral decadence, on the strength of what he wrote in the Symposium, even though he argued for legislation against homosexuality in the Laws; he has been condemned for the obscurity of his cosmology and for his totalitarian politics, his approach to state education sounding uncomfortably like the strategy behind the Hitler Youth.1 The adoption of the Atlantis allegory by the Nazis seriously damaged Plato’s reputation. Hitler admired Plato’s cyclical view of history involving periodic catastrophes and the return of the demi-gods, discussing it frequently with Hermann Rauschning, who observed, ‘Every German has one foot in Atlantis, where he seeks a better fatherland and a better patrimony. This double nature of the Germans [to live in both real and imaginary worlds] is especially noticeable in Hitler and provides the key to his magic socialism.’2 There is also a parallel, ‘alternative’ twentieth-century literature which has sometimes sought to establish the truth of Plato’s story by refuting what has been learnt through the natural sciences, and that too has alienated academics. Few scholars have been prepared to expose themselves to ridicule from their colleagues by discussing the matter, and it is symptomatic of the climate of opinion in the twentieth century that a young academic who saw a link between the Minoan civilization and Atlantis at the time of Evans’s Knossos excavation felt that he had to publish his ideas anonymously.3

The story which has produced such extremes of credulity and incredulity was written down for the first time that we can be certain of between 359 BC, when Plato returned to Athens from Sicily, and 351 BC, when he died at the age of 81. In a preamble he claimed the story had been handed down to his narrator, Critias, from a distinguished ancestor of Critias, the statesman Solon, who heard it in Egypt in about 590 BC. The Timaeus was written as a sequel to the Republic, and its opening pages show Socrates asking for a narrative to illustrate the ideal state in action.

Critias’ story about the war between Atlantis and the prehistoric Athenians is by no means the main part of the Timaeus, a seventy-five-page discourse on cosmology by the astronomer Timaeus. The discourse throws no light on Atlantis. At first sight it looks as if Plato realized the usefulness of the story only after completing the Republic, and slipped it into his next dialogue as an after-thought. It nevertheless reappears in the Critias (113C–121C), and the short account in the Timaeus (23D–25D) is really a trailer for that.4 The Timaeus version has one of the priests of Sais in Egypt lecturing Solon on the absence of any truly ancient traditions among the Greeks: ‘You remember but one deluge …’

23C ‘At one time, Solon, before the greatest destruction by water, what is now the Athenian state was the bravest in war and also supremely well organized in other respects. It is said that it possessed the finest works of art and the noblest polity of any nation under heaven of which we have heard tell.’

D On hearing this, Solon said that he marvelled, and with the utmost eagerness requested the priest to tell him in order and exactly all the facts about those citizens of old. The priest then said, ‘I will tell it, both for your sake and that of your city, and most of all for the sake of the Goddess who is both your patron and foster-mother and ours. Receiving the seed of you from Ge and Hephaestus, she founded your city first, a thousand years before ours,

E ‘of which the constitution is recorded in our sacred writings to be 8,000 years old. I will tell you in outline the laws of your citizens, who lived 9,000 years ago, and the noblest of their exploits: the full account we shall go through some other time, with the actual writings before us.

24A ‘To get a view of their laws, look at the laws here; for you will still find here many examples of those you had then. You see, first, how the priesthood is sharply separated off from the rest; next, the class of craftsmen, of which each sort works by itself without mixing with any other; then the class of shepherds, hunters and farmers.

B ‘The militia in particular, as no doubt you have noticed, is a class apart from all the others, compelled by law to devote itself exclusively to the work of training for war. A further feature is the character of their equipment with shields and spears; we were the first of the peoples of Asia to bear these weapons; it was the goddess who instructed us, just as she instructed you first of all the dwellers in your part of the world. Next, with regard to wisdom;

C ‘you see how much care our law has devoted from the very beginning to cosmology, by discovering all the effects which the divine causes produce upon human life, down to divination and the art of medicine which aims at health, and by its mastery also of all the subsidiary sciences. So when, at that time, the Goddess had furnished you, before all others, with this orderly and regular system, she established your city, choosing the spot where you were born since she perceived that its well-tempered climate would bring forth a harvest of men of supreme wisdom.

D ‘So it was that the Goddess, being herself both a lover of war and a lover of wisdom, chose the spot which was likely to bring forth men most like herself, and made this her first settlement. That is why you lived under the rule of such laws as these – yes, and laws still better – and you surpassed all men in every virtue, as became those who were the offspring and nurslings of gods. Truly, many and great are the achievements of your city, which are a marvel to men as they are here recorded; but there is one which stands out above all in heroic valour.

E ‘Our records relate how once your city stopped a mighty army as it insolently advanced to attack the whole of Europe, and Asia as well, from a distant base in the Atlantic Ocean. In those far-off days the ocean was navigable; for in front of the mouth which your countrymen tell me you call “the pillars of Heracles” there was an island larger than Libya and Asia together; and it was possible for the travellers of that time to cross from it to the other islands, and from the islands to the whole of the opposite continent which encircles the outer ocean.

25A ‘The sea that we have here, lying within the mouth just mentioned, is evidently a basin with a narrow entrance; what lies beyond is a real ocean, and the land surrounding it may rightly be called, in the fullest and truest sense, a continent. In this island of Atlantis there existed a confederation of kings, of great and marvellous power, which held sway over all the island, and over many other islands also and parts of the continent; and, moreover, of the lands here within the Straits they ruled over Libya as far as Egypt, and over Europe as far as Tuscany.

B ‘So this host, being all gathered together, made an attempt on one occasion to enslave by a single onslaught both your country and ours and the whole of the territory within the straits. It was then, Solon, that the manhood of your city showed itself conspicuous for valour and energy in the sight of all the world.

C ‘She took the lead in daring and military skill. Acting partly as leader of the Greeks, and partly standing alone by herself when deserted by all others, after encountering the deadliest perils, she defeated the invaders and set up her trophy. Those who were not as yet enslaved she saved from slavery; all the rest of us who dwell within the limits set up by Heracles she ungrudgingly set free.

D ‘But afterwards there occurred portentous earthquakes and floods, and in one terrible day and night of storm the whole body of your warriors was swallowed up by the earth, and Atlantis likewise was swallowed up by the sea and vanished; the ocean at that spot to this day cannot be navigated or explored, owing to the great depth of shoal mud which the island created as it subsided.’

The more detailed Critias breaks off at the moment where Zeus is about to pass judgement on the mortals. Since that moment in the 350s BC, the story of Atlantis has hovered between fable and folk tale, taken as history by some, acknowledged as allegory by others. Today some take it literally, others see it as didactic novella; in the ancient world too opinion was divided. Is the story true? If so, where was Atlantis? The longer version mentions ‘the extremity of the island near the Pillars of Heracles’ (Crit. 114B) and ‘the war between the dwellers beyond the pillars of Heracles [Atlanteans] and all that dwelt within them’ (Crit. 108E). The shorter version is clearer still: ‘in front of the mouth which [Greeks] call the pillars of Heracles, there was an island larger than Libya and Asia together’ (Tim. 24E). Plato is evidently describing an island-continent out in the Atlantic Ocean, just west of the Straits of Gibraltar. There are nevertheless possibilities other than the obvious one. Although Plato may have placed Atlantis far to the west in an ocean whose immensity was in his time only just being recognized, the original of his story, the Atlantis described by Egyptian priests 250 years earlier, was smaller and nearer to home. The term ‘Atlantic’ is misleading; as late as the first century BC, Diodorus (3. 38) was using it for the Indian Ocean, so it may be wiser to translate it less precisely as ‘outer’ or ‘distant’ ocean. We cannot assume ancient authors meant the same as us by either ‘pillars of Heracles’ or ‘Atlantic’.

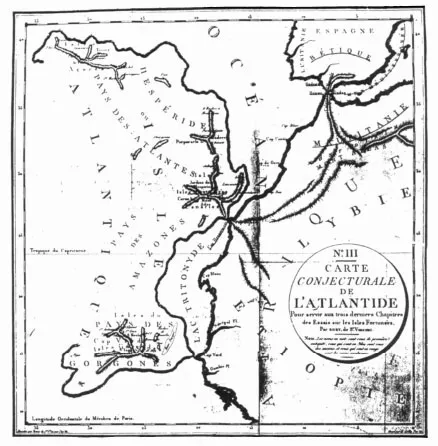

Figure 1.1 | A conventional ‘Atlantic’ Atlantis: Bory de St Vincent’s map (1803) |

Both place names and geographical perceptions shift with time, and the world of fourth-century Athens was already larger than the world of the Egyptian priests of 600 BC. To the Egyptians, a huge island in the ocean to the west could have been Sicily or even Crete. To th...