eBook - ePub

American Culture

An Anthology

- 440 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

American Culture

An Anthology

About this book

This second edition of American Culture includes contemporary events and provides an introduction to American civilization. Extracts are taken from diverse sources such as political addresses, articles, interviews, oral histories and advertisements.

Edited by academics who are highly experienced in the study and teaching of American Studies across a wide range of institutions, this book provides:

- texts that introduce aspects of American society in a historical perspective

- primary sources and images that can be used as the basis for illustration, analysis and discussion

- linking text which stresses themes rather than offering a simple chronological survey.

American Culture brings together primary texts from 1600 to the present day to present a comprehensive overview of, and introduction to, American culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access American Culture by Anders Breidlid, Fredrik Chr. Brøgger, Oyvind T. Gulliksen, Torbjorn Sirevag, Anders Breidlid,Fredrik Chr. Brøgger,Oyvind T. Gulliksen,Torbjorn Sirevag in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

American Indians

Introduction

1 Thomas Jefferson

“Confidential Message to Congress” (1803)

2 Tecumseh

“We All Belong to One Family” (1811)

3 Seattle

FROM “The Dead Are Not Powerless” (1854)

4 Helen Hunt Jackson

FROM A Century of Dishonor (1881)

5 US Congress

FROM The General Allotment Act (1887)

6 John Collier

“Full Indian Democracy” (1943)

7 Leslie Silko

“The Man to Send Rain Clouds” (1969)

8 Buffy Sainte-Marie

“My Country” (1971)

9 Studs Terkel

“Girl of the Golden West: Ramona Bennett” (1980)

10 Joy Harjo

“The Woman Hanging from the Thirteenth Floor Window” (1983)

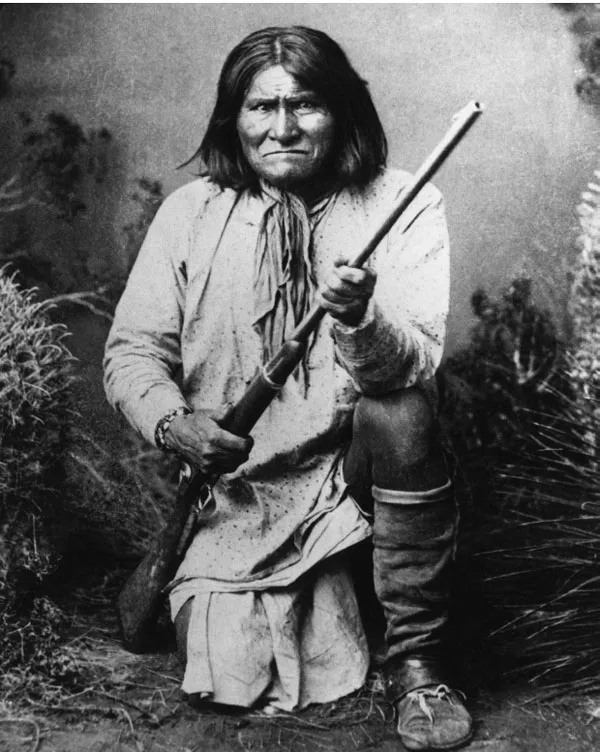

Figure 1 Portrait of Geronimo (1829–1900), American Apache chieftain, 1887 © Bettmann/CORBIS

Introduction

Although the socio-economic situation of the American Indians varies according to tribal and regional background, statistics clearly show that Indians across the nation, in cities as well as on reservations, are members of one of the most impoverished ethnic groups in the United States. In his address to a Senate sub-committee in March 1968 Robert Kennedy warned that “the first American is still the last American in terms of income, employment, health, and education. I believe his to be a national tragedy for all Americans – for we are in some ways responsible.”1

The dismal situation of the Indians is no new phenomenon. During the nineteenth century many liberal reformers rushed to defend the Indian cause. Already in his Notes on the State of Virginia (1785) Thomas Jefferson admitted that it is “very much to be lamented that we have suffered so many of the Indian tribes already to extinguish.”2 Yet, in The Declaration of Independence (1776) Jefferson had included a reference to “the merciless Indian savages.” Jefferson’s later views, as expressed in text 1, illustrate a common attitude of guilt, paternalism, and admiration for the Indian. His confidential message to Congress (1803) concerned funding for the Lewis and Clark expedition.

We have texts related to encounters between settlers and Indians in New England from the 1630s, but these are most often reports written by settlers who described what they understood as the “superstitions,” “errors,” and “imperfections” of the Indians they met. Captivity stories became a well-known genre. Oral literature continued to exist on its own terms among Indian tribes. During the 1800s Indian oratory probably became the genre of Native American literature best known to the reading public. Speeches of Indian leaders contain impassioned pleas for a lost cause. The speech by Tecumseh in this chapter (text 2) was given in 1810, three years before he died in battle. It is an attempt to unite various tribes for the purpose of regaining land in the Ohio valley. Speeches by Tecumseh and Seattle do not only serve as documents of a tragic past; they are often referred to by conservationists of today. Seattle’s speech (text 3) was addressed to the governor of Washington Territory in 1854. Even if his speech has a complicated (perhaps even dubious) origin, it is still a strong defence of Indian traditions.

During the 1870s Indian tribes were no longer regarded as separate nations by the American government. Military conflicts between Indians and US cavalry came to a stop as Indians had to relinquish land to a growing number of new immigrants. How the West was won from the Indians was later turned into mythic proportions by the American film industry. To the Indians, however, it was the end of a way of life. Black Elk’s famous eye-witness report from what has often been called the Wounded Knee massacre of 1890 from Black Elk Speaks (1932) is often anthologized and therefore not used here.

In 1881 Helen Hunt Jackson published her famous study A Century of Dishonor, a book-length indictment of what she considered to be the government’s disastrous neglect of the Indians (see text 4). A few years later (1887) Congress passed the General Allotment Act, based on the idea that transforming Indians into independent farmers would improve their situation (text 5). Whatever benign effects the Act was expected to produce, it is now regarded as at best a dubious venture.

During the 1930s John Collier, a Commissioner of Indian Affairs who had experience of social work in urban centers, became the architect responsible for the Indian New Deal (1934), a major effort of the F. D. Roosevelt administration to improve the situation of the Indians. Deploring the disastrous effects of the Allotment Act, Collier and his crew worked indefatigably to reintroduce and strengthen the tribe as a possible center of Indian life, here reflected in a memorandum Collier wrote about the topic in 1943 (text 6).

Over the last few years Indian writers have focused on their own situation, no longer as colorful victims but as keepers of a valid tradition within American culture. Among other prominent spokesmen, Vine Deloria, Jr., a Standing Rock Sioux, has analyzed the conditions of Indians from the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890 to a new generation of activists a hundred years later. Several books on Indian history have been written and scholarly journals such as American Indian Quarterly are published.

In “My Country,” the renowned Indian folk-singer Buffy Sainte-Marie, born in Canada, gives artistic expression to the sentiments of many Indians about their plight during the early 1970s (text 8). She was able to use popular music as an arena for her Indian songs, both traditional ballads and her own lyrics. Less militant in tone, contemporary Native American literature, including such writers as N. Scott Momaday (House Made of Dawn, 1969) and Louise Erdrich (Love Medicine, 1984), has gained general recognition over the last decades. Thus Leslie Silko’s short story (text 7), set among Pueblo Indians of the southwest, captures the tension between two cultures and two religions, “resolved” in this story by what may be understood as a tacit compromise. Silko was born in 1948 on the Laguna Reservation in New Mexico.

Traditional Indian values, such as reverence for nature, strong tribal ties, and the importance of storytelling, have influenced non-Indian writers in the United States. The famous Chicago journalist Studs Terkel’s interview with an Indian woman in the state of Washington (text 9) sheds light on current perceptions of the Indians’ situation.

The conflict between the Indians’ determination to control their own land and rivers and the attempts of private enterprise to exploit the resources on that land is still a potential powder keg. Indians themselves are sometimes in disagreement about the issues of how natural resources on reservation land should be used. In some states where gambling is illegal, casinos pop up on Indian land, which does not belong to the state in which it is situated. Some reservations profit from the gambling business, but it is not at all certain whether this is a secure and beneficial income in the long run.

Sometimes media focus on reservation land tends to take attention away from the large percentage of Native Americans now living in western and Midwestern cities, such as Chicago and Minneapolis. The contrast between country and city life is a continuing factor in Indian culture. Joy Harjo, a Creek Indian poet and musician, reflects on the plight of an urban Indian woman, torn between her present scene and her dreams of a reservation past (text 10).

Relocation (of Indians to the cities) and termination (of reservations as a federal responsibility) have been key political terms since the 1950s. The federal relocation program for the Navajos (today’s largest Indian group) and the Hopi Indians is just a case in point. Politicians from states with a large Indian population, such as South Dakota, need to address Indian issues. Nixon was praised for giving a place of ancient nature worship back to Indians; Reagan was in favor of reducing or ending the situation which in his mind reduced Indians to wards of the federal government.

The growing number of American Indian Studies courses in higher education is a sign of vast improvement. Such programmes are inducive, not only to scholarly interests in the field, but to a wide and genuine community commitment.

Questions and Topics

- What do the speeches of Tecumseh and Seattle have in common and how do they differ? How would you describe typical features of Indian oratory?

- In Collier’s opinion, how can Indian democracy be achieved? What are his arguments? Why were Americans reluctant to recognize the tribe as a legal entity?

- What does Silko’s short story tell you about the relationship between Indian religion and Catholicism? What causes the priest’s conflict and how is it resolved?

- What does Terkel’s text reveal about social and educational conditions for Indians? How does the Indian woman in the interview regard the past, present, and future of American Indians?

- What dilemma of Indian life does the woman in Harjo’s poem represent? What is the difference between being “set free” and climbing “back up to claim herself”?

1 Quoted in Helle H. Høyrup and Inger N. Madsen, Red Indians: The First Americans (Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1974), p. 5.

2 Thomas Jefferson, Query XI: Aborigines, Original Condition and Origin,” Notes on the State of Virginia, excerpted in The Heath Anthology of American Literature, Vol.1 (Lexington, Mass.: D.C. Heath and Co., 1990), p. 970.

Suggestions for further reading

Brown, Dee, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1970).

Hurtado, Albert L. and Peter Iverson, eds., Major Problems in American Indian History (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1994).

Lurie, Nancy Oestreich, Wisconsin Indians (Madison, Wis.: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, revised edn, 2002).

Sanders, Thomas E. and Walter W. Peek, eds., Literature of the American Indian (Columbus,Ohio: Glencoe Press, 1973).

Turner, Frederick, ed., The Portable North American Indian Reader (New York: Penguin, 1977).

1 Thomas Jefferson

Gentlemen of the Senate, and of the House of Representatives:

As the continuance of the act for establishing trading houses with the Indian tribes will be under the consideration of the legislature at its present session, I think it my duty to communicate the views which have guided me in the execution of that act, in order that you may decide on the policy of continuing it, in the present or any other form, or discontinue it altogether, if that shall, on the whole, seem most for the public good.

The Indian tribes residing within the limits of the United States have, for a considerable time, been growing more and more uneasy at the constant diminution of the territory they occupy, although effected by their own voluntary sales. And the policy has long been gaining strength with them of refusing absolutely all further sale, on any conditions; insomuch that, at this time, it hazards their friendship, and excites dangerous jealousies and perturbations in their minds to make any overture for the purchase of the smallest portions of their land.

A very few tribes only are not yet obstinately in these dispositions. In order, peaceably, to counteract this policy of theirs, and to provide an extension of territory which the rapid increase of our numbers will call for, two measures are deemed expedient. First, to encourage them to abandon hunting, to apply to the raising stock, to agriculture, and domestic manufacture, and thereby prove to themselves that less land and labor will maintain them in this better than in their former mode of living. The extensive forests necessary in the hunting life, will then become useless, and they will see advantage in exchanging them for the means of improving their farms, and of increasing their domestic comforts. Second, to multiply trading houses among them, and place within their reach those things which will contribute more to their domestic comfort than the possession of extensive, but uncultivated wilds. Experience and reflection will develop to them the wisdom of exchanging what they can spare and we want, for what we can spare and they want. In leading them to agriculture, to manufactures, and civilization; in bringing together their and our settlements, and in preparing them ultimately to participate in the benefits of our governments, I trust and believe we are acting for their greatest good.

At these trading houses we have pursued the principles of the act of Congress which directs that the commerce shall be carried on liberally, and requires only that the capital stock shall not be diminished. We, consequently, undersell private traders, foreign and domestic, drive them from the competition; and, thus, with the goodwill of the Indians, rid ourselves of a description of men who are constantly endeavoring to excite in the Indian mind suspicions, fears, and irritations toward us. A letter now enclosed shows the effect of our competition on the operations of the traders, while the Indians, perceiving the advantage of purchasing from us, are soliciting, generally, our establishment of trading houses among them. In one quarter this is particularly interesting.

The legislature, reflecting on the late occurrences on the Mississippi, must be sensible how desirable it is to possess a respectable breadth of country on that river, from our southern limit to the Illinois, at least, so that we may present as firm a front on that as on our eastern border. We possess what is below the Yazoo, and can probably acquire a certain breadth from the Illinois and Wabash to the Ohio; but, between the Ohio and Yazoo, the country all belongs to the Chickasaws, the most friendly tribe within our limits, but the most decided against the alienation of lands. The portion of their country most important for us is exactly that which they do not inhabit. Their settlements are not on the Mississippi but in the interior country. They have lately shown a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. American Indians

- 2. Immigration

- 3. African Americans

- 4. Women’s Studies

- 5. Government and Politics

- 6. Economy, Enterprise, Class

- 7. Geography, Regions, and the Environment

- 8. Art, Film, Music, and Popular Culture

- 9. Religion

- 10. Education

- 11. Language and the Media

- 12. Foreign Affairs

- 13. Ideology: Dominant Beliefs and Values