- 470 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The MPEG Handbook

About this book

A complete, professional 'bible' on all aspects of audio and video compression using MPEG technology, including the MPEG-4 standard and, in this second edition, H-264. The clarity of explanation and depth of technical detail combine to make this book an essential and definitive reference work.

THE MPEG HANDBOOK is both a theoretical and practical treatment of the subject. Fundamental knowledge is provided alongside practical guidance on how to avoid pitfalls and poor quality. The often-neglected issues of reconstructing the signal timebase at the decoder and of synchronizing the signals in a multiplex are treated fully here.

Previously titled MPEG-2, the book is frequently revised to cover the latest applications of the technology.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction to compression

1.1 What is MPEG?

MPEG is actually an acronym for the Moving Pictures Experts Group which was formed by the ISO (International Standards Organization) to set standards for audio and video compression and transmission.

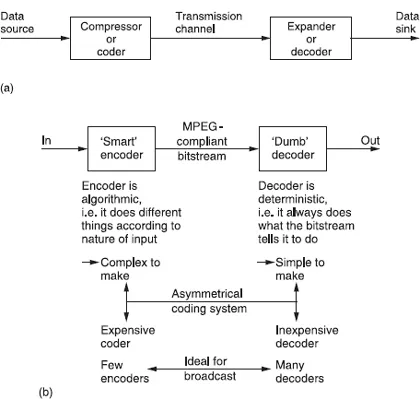

Compression is summarized in Figure 1.1. It will be seen in (a) that the data rate is reduced at source by the compressor. The compressed data are then passed through a communication channel and returned to the original rate by the expander. The ratio between the source data rate and the channel data rate is called the compression factor. The term coding gain is also used. Sometimes a compressor and expander in series are referred to as a compander. The compressor may equally well be referred to as a coder and the expander a decoder in which case the tandem pair may be called a codec.

Where the encoder is more complex than the decoder, the system is said to be asymmetrical. Figure 1.1(b) shows that MPEG works in this way. The encoder needs to be algorithmic or adaptive whereas the decoder is ‘dumb’ and carries out fixed actions. This is advantageous in applications such as broadcasting where the number of expensive complex encoders is small but the number of simple inexpensive decoders is large. In point-to-point applications the advantage of asymmetrical coding is not so great.

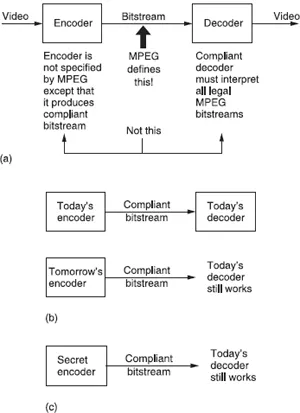

The approach of the ISO to standardization in MPEG is novel because it is not the encoder which is standardized. Figure 1.2(a) shows that instead the way in which a decoder shall interpret the bitstream is defined. A decoder which can successfully interpret the bitstream is said to be compliant. Figure 1.2(b) shows that the advantage of standardizing the decoder is that over time encoding algorithms can improve yet compliant decoders will continue to function with them.

Figure 1.1 In (a) a compression system consists of compressor or coder, a transmission channel and a matching expander or decoder. The combination of coder and decoder is known as a codec. (b) MPEG is asymmetrical since the encoder is much more complex than the decoder.

It should be noted that a compliant decoder must correctly be able to interpret every allowable bitstream, whereas an encoder which produces a restricted subset of the possible codes can still be compliant.

The MPEG standards give very little information regarding the structure and operation of the encoder. Provided the bitstream is compliant, any coder construction will meet the standard, although some designs will give better picture quality than others. Encoder construction is not revealed in the bitstream and manufacturers can supply encoders using algorithms which are proprietary and their details do not need to be published. A useful result is that there can be competition between different encoder designs which means that better designs can evolve. The user will have greater choice because different levels of cost and complexity can exist in a range of coders yet a compliant decoder will operate with them all.

MPEG is, however, much more than a compression scheme as it also standardizes the protocol and syntax under which it is possible to combine or multiplex audio data with video data to produce a digital equivalent of a television program. Many such programs can be combined in a single multiplex and MPEG defines the way in which such multiplexes can be created and transported. The definitions include the metadata which decoders require to demultiplex correctly and which users will need to locate programs of interest.

Figure 1.2 (a) MPEG defines the protocol of the bitstream between encoder and decoder. The decoder is defined by implication, the encoder is left very much to the designer. (b) This approach allows future encoders of better performance to remain compatible with existing decoders. (c) This approach also allows an encoder to produce a standard bitstream whilst its technical operation remains a commercial secret.

As with all video systems there is a requirement for synchronizing or genlocking and this is particularly complex when a multiplex is assembled from many signals which are not necessarily synchronized to one another.

1.2 Why compression is necessary

Compression, bit rate reduction, data reduction and source coding are all terms which mean basically the same thing in this context. In essence the same (or nearly the same) information is carried using a smaller quantity or rate of data. It should be pointed out that in audio compression traditionally means a process in which the dynamic range of the sound is reduced. In the context of MPEG the same word means that the bit rate is reduced, ideally leaving the dynamics of the signal unchanged. Provided the context is clear, the two meanings can co-exist without a great deal of confusion.

There are several reasons why compression techniques are popular:

| a | Compression extends the playing time of a given storage device. |

| b | Compression allows miniaturization. With fewer data to store, the same playing time is obtained with smaller hardware. This is useful in ENG (electronic news gathering) and consumer devices. |

| c | Tolerances can be relaxed. With fewer data to record, storage density can be reduced making equipment which is more resistant to adverse environments and which requires less maintenance. |

| d | In transmission systems, compression allows a reduction in bandwidth which will generally result in a reduction in cost. This may make possible a service which would be impracticable without it. |

| e | If a given bandwidth is available to an uncompressed signal, compression allows faster than real-time transmission in the same bandwidth. |

| f | If a given bandwidth is available, compression allows a better-quality signal in the same bandwidth. |

1.3 MPEG-1, 2, 4 and H.264 contrasted

The first compression standard for audio and video was MPEG-1.1,2 Although many applications have been found, MPEG-1 was basically designed to allow moving pictures and sound to be encoded into the bit rate of an audio Compact Disc. The resultant Video-CD was quite successful but has now been superseded by DVD. In order to meet the low bit requirement, MPEG-1 downsampled the images heavily as well as using picture rates of only 24–30 Hz and the resulting quality was moderate.

The subsequent MPEG-2 standard was considerably broader in scope and of wider appeal.3 For example, MPEG-2 supports interlace and HD whereas MPEG-1 did not. MPEG-2 has become very important because it has been chosen as the compression scheme for both DVB (digital video broadcasting) and DVD (digital video disk/digital versatile disk). Developments in standardizing scaleable and multi-resolution compression which would have become MPEG-3 were ready by the time MPEG-2 was ready to be standardized and so this work was incorporated into MPEG-2, and as a result there is no MPEG-3 standard.

MPEG-44 uses further coding tools with additional complexity to achieve higher compression factors than MPEG-2. In addition to more efficient coding of video, MPEG-4 moves closer to computer graphics applications. In the more complex Profiles, the MPEG-4 decoder effectively becomes a rendering processor and the compressed bitstream describes three-dimensional shapes and surface texture. It is to be expected that MPEG-4 will become as important to Internet and wireless delivery as MPEG-2 has become in DVD and DVB.

The MPEG-4 standard is extremely wide ranging and it is unlikely that a single decoder will ever be made that can handle every possibility. Many of the graphics applications of MPEG-4 are outside telecommunications requirements. In 2001 the ITU (International Telecommunications Union) Video Coding Experts Group (VCEG) joined with ISO MPEG to form the Joint Video Team (JVT). The resulting standard is variously known as AVC (advanced video coding), H.264 or MPEG-4 Part 10. This standard further refines the video coding aspects of MPEG-4, which were themselves refinements of MPEG-2, to produce a coding scheme having the same applications as MPEG-2 but with higher performance.

To avoid tedium, in cases where the term MPEG is used in this book without qualification, it can be taken to mean MPEG-1, 2, 4 or H.264. Where a specific standard is being contrasted it will be made clear.

1.4 Some applications of compression

The applications of audio and video compression are limitless and the ISO has done well to provide standards which are appropriate to the wide range of possible compression products.

MPEG coding embraces video pictures from the tiny screen of a videophone to the high-definition images needed for electronic cinema. Audio coding stretches from speech-grade mono to multichannel surround sound.

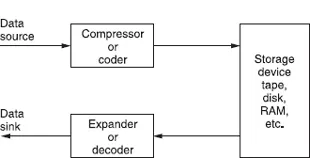

Figure 1.3 shows the use of a codec with a recorder. The playing time of the medium is extended in proportion to the compression factor. In the case of tapes, the access time is improved because the length of tape needed for a given recording is reduced and so it can be rewound more quickly. In the case of DVD (digital video disk aka digital versatile disk) the challenge was to store an entire movie on one 12 cm disk. The storage density available with today’s optical disk technology is such that consumer recording of conventional uncompressed video would be out of the question.

Figure 1.3 Compression can be used around a recording medium. The storage capacity may be increased or the access time reduced according to the application.

In communications, the cost of data links is often roughly proportional to the data rate and so there is simple economic pressure to use a high compression factor. However, it should be borne in mind that implementing the codec also has a cost which rises with compression factor and so a degree of compromise will be inevitable.

In the case of video-on-demand, technology exists to convey full bandwidth video to the home, but to do so for a single individual at the moment would be prohibitively expensive. Without compression, HDTV (high-definition television) requires too much bandwidth. With compression, HDTV can be transmitted to the home in a similar bandwidth to an existing analog SDTV channel. Compression does not make video-on-demand or HDTV possible; it makes them economically viable.

In workstations designed for the editing of audio and/or video, the source material is stored on hard disks for rapid access. Whilst top-grade systems may function without compression, many systems use compression to offset the high cost of disk storage. In some systems a compressed version of the top-grade material may also be stored for browsing purposes.

When a workstation is used for off-line editing, a high compression factor can be used and artifacts will be visible in the picture. This is of no consequence as the picture is only seen by the editor who uses it to make an EDL (edit decision list) which is no more than a list of actions and the timecodes at which they occur. The original uncompressed material is then conformed to the EDL to obtain a high-quality edited work. When on-line editing is being performed, the output of the workstation is the finished product and clearly a lower compression factor will have to be used. Perhaps it is in broadcasting where the use of compression will have its greatest impact. There is only one electromagnetic spectrum and pressure from other services such as cellular telephones makes efficient use of bandwidth mandatory. Analog television broadcasting is an old technology and makes very inefficient use of bandwidth. Its replacement by a compressed digital transmission is inevitable for the practical reason that the bandwidth is needed elsewhere.

Fortunately in broadcasting there is a mass market for decoders and these can be implemented as low-cost integrated circuits. Fewer encoders are needed and so it is less important if these are expensive. Whilst the cost of digital storage goes down year on year, the cost of the electromagnetic spectrum goes up. Consequently in the future the pressure to use compression in recording will ease whereas the pressure to use it in radio communications will increase.

1.5 Lossless and perceptive coding

Although there are many different coding techniques, all of them fall into one or other of these categories. In lossless coding, the data from the expander are identical bit-for-bit with the original source data. The so-called ‘stacker’ programs which increase the apparent capacity of disk drives in personal computers use lossless codecs. Clearly with computer programs the corruption of a single bit can be catastrophic. Lossless coding is generally restricted to compression factors of around 2:1.

It is important to appreciate that a lossless coder cannot guarantee a particular compression factor and the communications link or recorder used with it must be able to function with the variable output data rate. Source data which result in poor compression factors on a given codec are described as difficult. It should be pointed out that the difficulty is often a function of the codec. In other words data which one codec finds difficult may not be found difficult by another. Lossless codecs can be included in bit-error-rate testing schemes. It is also possible to cascade or concatenate lossless codecs without...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Introduction to compression

- Chapter 2 Fundamentals

- Chapter 3 Processing for compression

- Chapter 4 Audio compression

- Chapter 5 MPEG video compression

- Chapter 6 MPEG bitstreams

- Chapter 7 MPEG applications

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The MPEG Handbook by John Watkinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.