![]()

![]()

1

The quality and design of streets have always been important issues for walking and more details on this are provided in the final chapter. Some specific street layouts are more popular with pedestrians than others. Narrow medieval streets, crooked lanes and numerous irregular squares made walking interesting and easy when only a few vehicles could access them because the streets were too narrow. However, historically these streets were mostly filthy and rich people hardly used them. This changed during the 19th century when main drains were constructed and most street areas could be converted into cleaner space.

The renaissance and baroque street layouts that developed during the 15th and 16th centuries changed all this. The streets became wide and straight and the squares large and more geometrical. But it was only in the 18th and even more so in the 19th century when the number of coaches and carriages increased and crossing a road as a pedestrian became more difficult and often dangerous that sidewalks were built to safeguard pedestrians and also to keep them away from busy carriageways. Unfortunately, relatively little is known about when the first sidewalks were built.1

The avenues of earlier centuries which were often used for marching changed largely into boulevards during the 19th century. These were streets for pleasurable walking on a scale previously unknown. Normally the wide central reservations of such streets were bordered by trees and used by pedestrians for strolling and mutual admiration. The central walkway also offered the best view of the newly constructed public and private buildings. Furthermore, boulevards had generous sidewalks with even more rows of trees. There was space for everybody from the students and workers on foot to the aristocrats on horseback and the ladies in carriages. In short, this mixing of the different classes had been unknown in previous centuries. Many boulevards were modeled on Paris; the new plan developed by Napoléon III and put into practice by the new prefect Georges-Eugéne Haussmann.2 The Haussmann Plan of Paris started in 18493 and was completed in 1898 (Carmona 2002, p. 149). It was the desired street layout for many cities, not only in Europe but also in the New World, in particular for capital cities such as Berlin and Vienna. Although the Haussmann Plan destroyed most of the previous city, it left the historic monuments intact. It was urban renewal on a scale and with a brutality only known following the large fires that plagued many cities. In a sense, the demolition matched the destruction that occurred during urban motorway building a century later, but maybe that is a lame comparison because the biggest assets of this plan were the creation of numerous boulevards, parks and gardens. What the effect was on walking and healthier living we do not really know but it did create the space for more wheeled traffic and later on for cars.

The majority of North American towns still had nothing like that. Residential and public buildings were constructed along a grid street layout. This was easy, cheap and did not involve sophisticated planning but not all North American cities were happy with this type of street plan and it is here where our story starts.

Innovative Street Layouts

Who actually had control over streets and alignments in most US cities was by no means clear. To facilitate improvement, street commissioners were appointed at the beginning of the 19th century, at least in the large east coast cities. However, they were often powerless if private owners subdivided land and designed streets to their own liking. Even by the turn of the 20th century, it was only Pennsylvania that had passed legislation requiring every municipality to have an overall plan for its streets and alleys. Its major city Philadelphia had already developed a tradition of regulated urban expansion and street planning since its foundation in 1682 (Reps 1965, pp. 161, 169). Altogether Philadelphia had a very sophisticated street network consisting of different street widths, with some of the streets being very narrow and paved with cobblestones. The Intra City Business Property Atlas by Franklin (1939) shows how varied the street widths were (and still are).

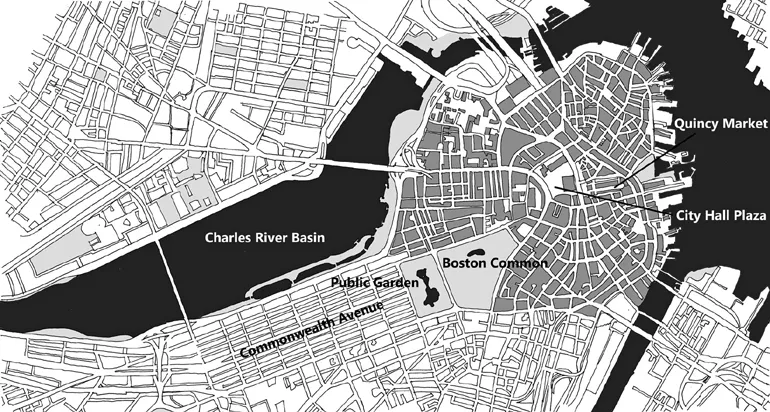

Boston (Massachusetts) also had a European street pattern, even more so than Philadelphia. Boston’s street network even as late as 1929 was reminiscent of a medieval city, except for Boston Common and the Public Garden (the parks close to the city center) (Capan map of Boston 1929). Jacobs (1995) describes how the street layout changed over a relatively short time period, mostly because of public redevelopment and road projects (pp. 264–265).

Figure 1.1

Street map of Boston

Possibly the most interesting street plan in North America was developed by J, E. Oglethorpe for Savannah. The settlement was founded in 1733, about 60 years later than Charleston (1670). Oglethorpe and his colonists settled about 16 miles inland from the coast, on the Savannah River (Wilson 2012, pp. 101–102). Although the street layout is a grid, the high number of squares changes the street appearance and these squares form their own wider ‘green’ grid. It made walking from square to square an enjoyment in nearly all seasons (for more details see ‘Savannah’ in Chapter 14).4

Another street plan, which was quite widely imitated, was that of Washington, DC. Pierre Charles L’Enfant, a self-made engineer, designed the city at the end of the 18th century (1791). The main avenues were extremely wide and bordered with trees (160–400ft/52.5–131m) and they had plenty of space for walking (Reps 1965, pp. 250–251). L’Enfant was of French origin and his ideas were influenced by the designs of Paris and Versailles, though he had also studied street plans of other European cities (ibid, p. 247). Several other towns, for instance Buffalo, Detroit, Indianapolis, Madison (ibid, p. 325), were strongly influenced by Washington’s street plan (see Figure 13.12: map of Washington DC).

Daniel H. Burnham and Edward H. Bennett introduced a Plan of Chicago to the public in 1909; again it showed some similarities to the Haussmann Plan of Paris. It consisted primarily of wide boulevards, diagonal roads, and large squares and parks (Hines 1974, pp. 328–329). A remarkable street hierarchy was suggested and it already included elements of traffic division. Through traffic was to be separated from residential traffic. The boulevards, the widest being 572ft (188m),5 had been designed by Frederick Law Olmsted’s firm6 (Condit 1973, pp. 32, 73). The Chicago Plan stimulated similar improvements in other cities, for example Minneapolis (Heckscher and Robinson 1977, p. 22).

From the middle of the 19th century, a new movement had derived largely from English landscape gardening. The main characteristic in terms of street design was the heavily curved street, which was in total contrast to the conventional street block. Such designs were first applied for walkways through cemeteries and later parks. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux became well known for the design of Central Park in New York (1858). Olmsted had visited Birkenhead Park near Liverpool after the first people’s park had opened to the public in 1847. Olmsted (1852) admitted that nothing like that was known in the United States (pp. 78–79). It has been argued that Olmsted had copied Birkenhead Park with its separate footpaths and a carriageway drive when designing Central Park in New York, but the footpaths and street design in Central Park are not really comparable with Birkenhead.

He also influenced street planning in some suburban housing developments. One of the best known is Riverside, Illinois, near Chicago (1869). The street layout of Riverside includes some large green areas and a variety of street widths (Reps 1965, pp. 344–345).

Another of his plans was for a workers’ town commissioned by the Apollo Iron and Steel Company of Pennsylvania. It was named Vandergrift and is located about 30 miles northeast of Pittsburgh. Vandergrift was the second ‘New Town’ for workers around a factory in the United States.7 The first plots for sale were available in the town in 1896 (Vandergrift Centennial Committee 1996, p. 25).

Vandergrift was built in the large bend of the river Kiskiminetas. Olmsted’s town plan fitted beautifully into this bend. As the river so is the street network; all the streets are curved. Vandergrift’s streets were paved with yellow bricks, all had sidewalks and trees were planted along most streets. It had tree-lined greens and its own park (today called Kennedy Park). In addition, a green belt went through the town and although it was not a garden city, it came close to it.

Figure 1.2

Olmsted’s original plan of Vandergrift

Even so, it was not really a town for the working class, only the skilled and well-paid workers and the business owners could afford the prices for both the plot and the construction of a house (ibid, p. 25). The unskilled and low-paid laborers lived near Vandergrift, for example in Vandergrift Heights, which had developed at about the same time as Vandergrift. But Vandergrift Heights was not a workers’ paradise, there was no street plan and the streets were unpaved; sidewalks, if they existed at all, were made out of boards, all the luxuries of Vandergrift were missing and the plots and houses were small and without bathrooms (ibid, p. 43).

The son of Frederick Law Olmsted was even more prolific than his father. He designed Forest Hills G...