![]()

CHAPTER 1

Carnegie and Frick

The two most important individuals involved in the Homestead Strike were undoubtedly Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick. It was these two individuals, more than anyone else, who set in motion the tragic events at Homestead. To fully comprehend what happened at Homestead, it is essential to understand a few things about both Carnegie and Frick. The first is that while both saw themselves as “self-made men,” or individuals who achieved great wealth and power through nothing but their own intelligence and hard work, the truth is more complicated. Both Frick and Carnegie got their start using money and connections provided by their families or mentors. Both men consistently resorted to questionable tactics and unethical behavior to ensure high rates of return on their investments. Once established, they organized or joined industry organizations and supported special interest legislation that effectively prevented new competitors from competing with their businesses, effectively stymieing other would-be “self-made men.”

Andrew Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland, on November 25, 1835, to William and Margaret Carnegie. William Carnegie was a weaver who worked out of the family’s house, and he was a Chartist, supporting a political philosophy that advocated universal male suffrage and annual parliamentary elections, demands that were radical for the time. William was not the only radical in Andrew’s family; Margaret’s father could always be counted on to appear at local town meetings and heckle his conservative political opponents. Her brother, Tom Morrison, pressed the workers of Dunfermline to walk off the job in solidarity with the miners in nearby Clackmannan County after the latter went out on strike.1 During the 1840s, Carnegie’s father and uncles led strikes as technological advances and worsening economic conditions made providing for their families impossible. In other words, from a very young age, Andrew Carnegie was continually exposed to a radical, pro-labor politics that was at great variance with the actions he later took as an adult.

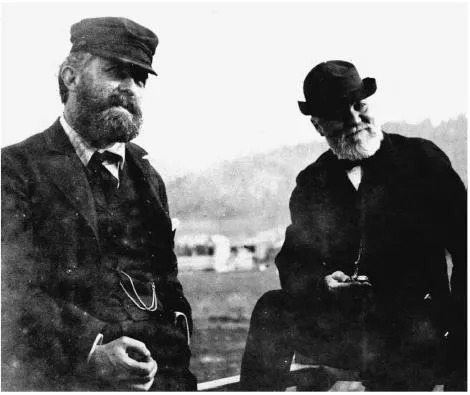

Figure 1.1 Henry Clay Frick (left) and Andrew Carnegie (right) were two of America’s leading industrialists and the two men most responsible for the violence at Homestead in July 1892.

Courtesy of The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives.

One reason for their radicalism was the fact that the late 1840s were lean times in Scotland. Called the “Hungry Forties,” work for men such as William evaporated; between 1840 and 1850, the number of handloom weavers declined from approximately 85,000 to about 25,000 a drop of almost 70 percent. The massive unemployment sparked food riots all over Scotland, and the Carnegie family’s modest circumstances worsened.2 Margaret was forced to sell vegetables and sweetmeats or take in piecework to supplement the family’s meager income. As a result, William Carnegie decided to move his family to the United States, but poverty forced him to accept a loan from one of Margaret’s childhood friends in order to purchase the tickets. In May 1848, when Andrew was 13, the Carnegies crossed the Atlantic and began their lives in the “New World.”

The Carnegies settled in Allegheny County, where Margaret’s sisters lived. Like many recent immigrants, the Carnegies were poor; the name of their neighborhood—Barefoot Square—was a testament to the deprivations they suffered. William initially tried to manufacture and sell his weaving, but he was unable to compete with the cheap, mass-produced goods pouring out of America’s expanding factories. Worse, William’s income did not meet the family’s needs, so Margaret again took in piecework binding shoes. Eventually, her income exceeded William’s, which only demoralized the proud Scot. Years later, Andrew reflected on these events and, implicitly blaming his father for being unable to adapt to the changing economic climate, said, “My father did not recognize the impending revolution and was struggling under the old system.”3

Andrew Carnegie first worked in a factory that manufactured bobbins (cylinders on which yarn, thread, or wire is wound), where he was paid $1.20 for a 72-hour week. It was not long before factory owner, John Hay, approached Carnegie to draft some letters; apparently, Hay had poor handwriting and was so impressed with Carnegie’s penmanship that he paid the teenager to draft the invoices sent to the factory’s customers. Seeing an opportunity, Carnegie took evening classes in accounting during the winter of 1849 and used what he learned to increase his skills (and income). That spring, Carnegie’s uncle found the boy a position as a messenger for the Ohio Telegraph Company, which paid more than double what Carnegie had earned in the bobbin factory. This was the first instance of a family member or well-placed acquaintance securing a lucrative position or investment opportunity for Carnegie, and it became an essential ingredient in his early success.

Carnegie was soon promoted to telegraph operator and, by 18, was working for the Pennsylvania Railroad Company’s manager (and future president), Thomas A. Scott, as secretary/telegraph operator.

In this position, Carnegie wielded considerable power, often acting in his boss’ name without Scott’s prior approval. Fortunately, Carnegie’s brash behavior almost always worked out well for him, a fact that quickly endeared him to Scott. This early success reinforced his belief that he was smarter than many of his contemporaries, a feeling that, by middle age, hardened into arrogance and contributed to an implicit belief that the rules did not apply to him.

Soon, Scott was including Carnegie in his investments (the first of which Carnegie financed with a loan from Scott), and by 1858, Carnegie was earning an annual dividend of $5,000 per year.4 Success bred more success as Carnegie consistently reinvested his gains into railroad-related industries. In the spring of 1861, Scott (who was now serving as Assistant Secretary of War) appointed the 26-year-old Carnegie as superintendent of the military railways and the federal government’s eastern telegraph lines, a lucrative position that gave Carnegie multiple opportunities to increase his personal wealth. In other words, Carnegie’s early success had far more to do with being in the right place at the right time than in any personal qualities.

Thomas A. Scott (1823–1881)

Thomas Alexander Scott was a wealthy and politically influential industrialist. Scott was born in Fort Loudoun, a small town in Central Pennsylvania. In 1850, he accepted a position as a station agent with the Pennsylvania Railroad and rose quickly through the company’s ranks; within a decade, he was the company’s vice president. Briefly serving as the Union Pacific Railroad’s president in the early 1870s, Scott became president of the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1874 and was largely responsible for its growth into one of the nation’s leading railroads.

Scott’s wealth and power made him influential in the state’s nascent Republican Party. In the early months of the Civil War, Pennsylvania’s first Republican governor, Andrew G. Curtin (1861–1867) commissioned Scott a colonel and, shortly thereafter, Abraham Lincoln appointed Scott Assistant Secretary of War. Drawing on his professional experience, Scott eventually coordinated and supervised the federal government’s railroads. Following the war, Scott played a prominent role in Reconstruction, the federal government’s process of readmitting the former Confederate states back into the Union.

In large measure, Scott’s success was due to the fact that he was aggressive, ruthless, manipulative, and willing to operate in ethical gray areas in search of greater profit. For instance, Scott and Pennsylvania Railroad president J. Edgar Thomson participated in a price-fixing cartel with the managements of Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and Ohio and Mississippi Railroad (among others) that ensured fat profits by limiting competition. Scott manipulated the media by promising newspapers additional advertising in exchange for favorable coverage, and he was not above offering influential journalists and government officials “gifts” in exchange for favorable treatment. During the Civil War, Congress investigated Scott for price-gouging the government; the investigation turned up evidence that Scott favored the Pennsylvania Railroad when it came to directing federal government rail traffic in order to raise the company’s profits. All of these were methods that Carnegie later employed in building his steel empire.

Another method of ensuring a healthy bottom line was for Thomson, Scott, and Carnegie to invest their private money in an idea or product for which their other businesses (in this case, the Pennsylvania Railroad) would be an enthusiastic customer. One good example was Theodore T. Woodruff’s improved design for sleeping cars, a train car whose seats could be converted into beds so that passengers could sleep during long trips. In the late 1850s, Thomson and Scott ordered four of Woodruffs sleeping cars for use on the Pennsylvania Railroad. This was good news for Woodruff, but he lacked the funds to actually build the cars at the time (he had only a single demonstration model). Thomson and Scott offered capital in exchange for shares in Woodruff’s company; since they had committed the Pennsylvania Railroad to buying Woodruffs sleeper cars, their investment was guaranteed to be a good one. Scott encouraged his protégé to invest in the company as well, which Carnegie did by taking a loan from a local bank. There is nothing illegal about this sort of “can’t lose” investment, but it does demonstrate that Carnegie’s rise to wealth had less to do with intelligence and hard work than ready access to capital and the good fortune of knowing people (such as Scott and Thomson) whose own wealth gave them the means to ensure a decent return on their investments.

However, it was in the growing demand for iron products that Carnegie saw his future success. The Civil War stimulated intense demand for military equipment (cannons, shells, armor plating, rifles, etc.) that was largely made of iron, driving up the price per ton. A self-described pacifist, Carnegie did not have to serve in the Union Army because he paid a poor Irish immigrant $850 to volunteer as a substitute; this left Carnegie free to exploit the vast opportunities for wealth created by the war. In 1864, Carnegie formed the first of multiple iron-related companies in the hopes of capitalizing on the boom, which he did; during this period, he bragged to a former coworker, “I’m rich; I’m rich,” and by 1868, his business interests included bridge-building, railroads, petroleum, telegraphy, and finance, which brought him a combined return of over $56,000 per year.5 Just as before, Carnegie kept investing his wealth into his companies, using the capital to improve technology, a hallmark of his approach to business throughout his life.

By the early 1870s, Carnegie began rethinking the sprawling and diverse nature of his empire. He decided to consolidate, or, as he later put it in his autobiography, “put all good eggs in one basket.”6 Undoubtedly, this new approach was encouraged by the fact that he, Thomas Scott, and J. Edgar Thomson (president of the Pennsylvania Railroad) were voted off the Union Pacific’s board of directors under a cloud of scandal. Thus, in autumn of 1872, he formed Carnegie, McCandless & Company, establishing a steel plant just outside of Pittsburgh in Braddock’s Field. The depression triggered by the Panic of 1873 caused the firm some financial difficulties, and it was reorganized in 1874 as the Edgar Thomson Steel Company, which quickly became both the country’s leading rail producer and America’s most technologically advanced steel mill. While many companies failed due to the depression, Carnegie’s firm continued to expand during this period, taking advantage of cheap wages to enlarge its production facilities. Growth was slow at first, but by the late 1870s, Carnegie had elbowed his way into the influential Bessemer Steel Asso...