![]()

1

Introduction

Published in 1989, Blueprint for a Green Economy (henceforth BGE) presented, for the first time, practical policy measures for “greening” modern economies and putting them on a path to sustainable development.

BGE had one over-arching theme. Making economies more sustainable requires urgent progress in three key policy areas: valuing the environment, accounting for the environment, and creating incentives for environmental improvement. Today, with the threat of global warming, the decline in major ecosystems and their services, and fears over energy security, achieving these goals is even more vital. In fact, they are essential to economic welfare and the well-being of current and future generations. Chapter 2 discusses in more detail some of the key global environmental trends and initiatives that have occurred over the past 20 years, and explains why they make the main messages of BGE even more relevant today. Here, in this introductory chapter, we provide a brief summary of the key theme and messages of BGE.

Nature as capital

One of the important contributions of BGE was to argue that the natural environment should be viewed as a form of capital asset, or natural capital. Although we were not the first economists to adopt this perspective,1 BGE sought to demonstrate that efficient management of an economy’s natural resource and environmental endowment is essential to achieving the overall goal of sustainable development.

BGE maintained that it is important not to restrict the concept of natural capital just to those natural resources, such as minerals, fossil fuels, forests, agricultural land and fisheries, that supply the raw material and energy inputs to our economies. Nor should we consider the capacity of the natural environment to assimilate waste and pollution the only valuable “service” that it performs. Instead, natural capital is much broader, encompassing the whole range of goods and services that the environment provides. Many have long been considered beneficial to humans, such as nature-based recreation, eco-tourism, fishing and hunting, wildlife viewing, and enjoyment of nature’s beauty. However, a wide range of environmental benefits also arise through the natural functioning of ecosystems, which are distinct systems of living organisms and communities interacting with their physical environment. Examples of such ecosystem goods and services include water supply and its regulation, climate maintenance, nutrient cycling, enhanced biological productivity and, ultimately, overall life support.

Today, the term “natural capital” is frequently employed to define an economy’s environment and natural resource endowment – including ecosystems.2 Humans depend on and use this natural capital for a whole range of important benefits, including health and sustenance. For all these reasons, our natural wealth is extremely valuable. But unlike skills, education, machines, tools and other types of human and physical capital, we do not have to manufacture and accumulate our endowment of natural assets. Nature has provided this endowment and its benefits to us as part of humankind’s common heritage; we have not had to create these assets ourselves.

Yet perhaps because this capital has been endowed to us, we humans have tended to view it as limitless, abundant and always available for our use. The result is that present-day economies have often ended up overexploiting natural capital in the pursuit of economic development, growth and progress. The unfortunate result is that generations today are leaving too little for future generations to use and benefit from. Over the long term, the consequence is to undermine economic growth and human well-being.

Sustainable development

The crucial relationship between the management of natural capital and “sustaining” economic development was an important theme in BGE. By the late 1980s, the concept of sustainable development had become popular, and one could pick and choose from many interpretations. As noted at the beginning of BGE:

Definitions of sustainable development abound. There is some truth in the criticism that it has come to mean whatever suits the particular advocacy of the individual concerned. This is not surprising. It is difficult to be against “sustainable development.” It sounds like something we should all approve of, like “motherhood and apple pie.”3

Yet, by the late 1980s, there was also an emerging consensus definition of sustainable development, which was put forward by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) – often referred to as the “Brundtland Commission” after its chairperson, former Norwegian prime minister Gro Harlem Brundtland. The WCED defined sustainable development as:

Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.4

As explained in Chapter 3, the Brundtland Commission’s definition especially appeals to economists as it is consistent with a capital approach to sustainable development. That is, it is the total stock of capital employed by the economic system, including natural capital, that determines the full range of economic opportunities, and thus well-being, available to both present and future generations. Society must decide how best to use its total capital stock today to increase current economic activities and welfare, and how much it needs to save or even accumulate for tomorrow and, ultimately, for the well-being of future generations.

However, it is not simply the aggregate stock of capital in the economy that may matter but also its composition. In particular, an important issue is whether present generations are running down one type of capital to meet today’s needs and accumulate other forms of wealth, and whether this change in the composition of capital will make future generations worse or better off.5

In particular, there is concern that current economic development may be leading to rapid accumulation of physical and human capital, but at the expense of excessive depletion and degradation of natural capital. By depleting the world’s stock of natural wealth irreversibly, development today could have detrimental implications for the well-being of future generations. That is, today’s pattern of economic development could very well be highly “unsustainable.”

The economy–environment tradeoff

Compared to previous approaches to environmental policy, BGE offered a different perspective on the key economy–environment tradeoff underlying development. For example, as the book noted:

In the 1970s it was familiar for the debate about environmental policy to be couched in terms of economic growth versus the environment. The basic idea was that one could have economic growth – measured by rising real per capita incomes – or one could have improved environmental quality. Any mix of the two involved a tradeoff – more environmental quality meant less economic growth, and vice versa.6

BGE argued instead that, although there must be some “tradeoffs” between narrowly construed economic growth and environmental quality, it is incorrect to suggest that all environmental policy choices amount to a fundamental “economic growth versus the environment” tradeoff. To the contrary, as suggested by BGE:

There will be situations in which growth involves the sacrifice of environmental quality, and where conservation of the environment means forgoing economic growth. But sustainable development attempts to shift the focus to the opportunities for income and employment opportunities from conservation, and to ensuring that any tradeoff decision reflects the full value of the environment.7

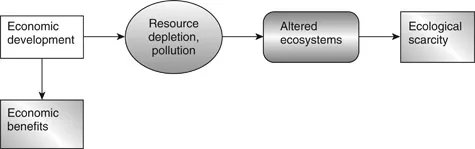

The true economy–environment tradeoff, then, is in how one achieves economic development and enhanced human well-being. Natural resource depletion, pollution and ecological degradation arise through a fundamental tradeoff in our use of the environment. This tradeoff can be depicted in a simple diagram (see Box 1.1). Economic development cannot proceed without exploiting natural resources for raw material and energy inputs or using the environment to assimilate pollution and other waste by-products. On the positive side, economic development also leads to the increased production and consumption of human-made goods and services. As these goods and services contribute to overall human welfare, they can be considered the “economic benefits” of development. However, the exploitation and use of

BOX 1.1 The Economy–Environment Tradeoff

As economic development proceeds, it generates many economic benefits through the production and consumption of commodities. However, development also leads to natural resource depletion, pollution and the alteration of ecosystems. The latter can lead to ecological scarcity, i.e. the relative decline in beneficial ecosystem goods and services. Thus, the fundamental economy–environment tradeoff is between the economic benefits arising from development and any resulting environmental and welfare impacts arising from natural resource depletion, pollution and ecological degradation.

the natural environment by humans for raw materials, energy and waste assimilation also leads to the alteration of ecosystems. The disruption and destruction of ecosystems affect, in turn, their various contributions to human welfare, such as the use of aesthetic landscapes for recreation, the maintenance of beneficial species, the control of erosion, protection against floods or storms, and so forth. The loss of these “ecological benefits,” or ecosystem goods and services, as the consequence of economic development can be considered increasing ecological scarcity.8

The economy–environment tradeoff depicted in Box 1.1 also amounts to a choice between accumulating versus depreciating two different types of capital. The first type is what BGE called “man-made capital,” which consists of human and physical capital, or “the stock of all man-made things such as roads and factories, computers, and human intelligence.”9 The second type of asset is an economy’s endowment of natural capital. The choice between increased economic benefits and increased pollution, natural resource depletion and ecological scarcity is therefore really about a tradeoff between these two different assets. On the one hand, we are creating economic wealth in the form of human-made capital; on the other, we are sacrificing our available “natural wealth” to do so.10

Environmental valuation

Simply because an economy–environment tradeoff exists does not mean that it should be eliminated. In fact, it is technologically infeasible for modern economies to produce and consume commodities without generating some pollution, depleting natural resources and altering ecosystems. Even if we aimed for “zero growth” in today’s economies, they would still lead to considerable environmental impacts.

As BGE maintained, not only must we be aware that such a fundamental economy–environment tradeoff exists but also that attaining sustainable economic development requires that we value fully any environmental impacts arising from our development choices:

If there is to be a trade-off, society must choose on the basis of a full understanding of the choice in question. That means the economic value of the environmental cost, if one is to be incurred, must be understood. … Rational trade-offs mean valuing the environment properly. … There must be informed choice, not choice based on the presumption that the environment is a free good.11

BGE placed great importance on correcting the “undervaluation” of the environment, because it lies at the heart of why present-day economic development is inherently unsustainable. As David Pearce suggested in his summary of BGE:

Valuation is essential if we are to “trade-off” forms of capital. … but careful inspection of the values of natural capital (i.e. looking at what environmental assets do for us) will show that the trade-off has been biased in favour of either “consuming” the proceeds (i.e. not reinvesting at all) or investing too readily in man-made assets. Very simply, if the “true” value of the environment were known, we would not degrade it as much.12

Thus, a key message of BGE was that: “By at least trying to put money values on some aspects of environmental quality we are underlining the fact that environmental services are not free.”13

Box 1.2 contains an excerpt from BGE that explains why ignoring environmental values undermines both sustainable development and economic policy. As this passage concludes, not only must the various “services” of natural capital be valued correctly, but these correct values must be integrated into economic policy.

Over the past 20 years since BGE, economic methodologies and approaches for environmental valuation have improved substantially, and...