![]()

PART I: OVERVIEW

In recent years, a substantial quantity of research has been conducted in the area of consumer behavior in tourism. While results varied greatly, most studies determined that motivation played a major role in determining tourists’ behavior. Accordingly, motivation determines not only if consumers will engage in a tourism activity or not, but also when, where, and what type of tourism they will pursue.

In Chapter 1, Hudson summarizes some of the most popular theories that have been proposed for describing how consumers’ motivation affects their tourism behavior and actions. Among the theories discussed in detail are Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, Murray's Classification Scheme, Dann's Tourism Motivator, Crompton's Nine Motives, and Plog's Tourism Motivation Model. All of these models focus on the needs and motivations of individuals and the influence these needs have on their tourism behavior.

Findings based on surveys conducted by Perreault and the Gallup Organization which questioned the travel behavior of thousands of people, support the long-held belief that travelers can be divided into numerous categories, based on their reason and motivation to travel.

In addition to travel motivation, Hudson also discusses the traveler's destination choice process. Under this category fall theories such as those of Muller, Um, and Crompton, Woodside and Lysonski, and Mansfeld. Finally, Hudson presents some comprehensive models of consumer behavior in tourism. Models such as Wahab, Crampon, and Rothfield's, Mayo and Jarvi's, and Moutinho try to analyze the effects that the individual, environmental, and situational factors have on tourists’ behavior and choice.

The chapter concludes with the observation that while extensive research has been conducted on why, where, and when individuals travel, there still is a lack of understanding of why some consumers do not travel. Hudson contends that the subject of nonusers in tourism is a relatively unexplored area partly because of the difficulty of properly researching it.

![]()

Chapter 1

Consumer Behavior Related to Tourism

Simon Hudson

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of the chapter the reader should:

• Understand the importance of consumer behavior within tourism marketing

• Have a broad grasp of the part played by motivational factors in tourism behavior

• Understand why tourism researchers have tried to explain tourist behavior by developing typologies of tourist roles

• Be familiar with various studies that have attempted to understand the destination choice process

• Have a general understanding of the usefulness and limitations of consumer behavior models developed over the years

MOTIVATION OF TOURISTS

Many authors see motivation as a major determinant of the tourist's behavior. Central to most content theories of motivation is the concept of need. Needs are seen as the force that arouses motivated behavior and it is assumed that, to understand human motivation, it is necessary to discover what needs people have and how they can be fulfilled. Maslow in 1943 was the first to attempt to do this with his needs hierarchy theory, now the best known of all motivation theories (see Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1. Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

Physiological needs | Hunger, thirst, sex, sleep, air, etc. |

Safety needs | Freedom from threat or danger |

Love (social) needs | Feeling of belonging, affection, and friendship |

Esteem needs | Self-respect, achievement, self-confidence, reputation, recognition, prestige |

Needs for self-actualization | Self-fulfillment, realizing one's potential |

Source: Maslow, 1943.

Maslow's theory was originally developed in the context of his work in the field of clinical psychology, but has become widely influential in many applied areas such as industrial and organizational psychology, counseling, marketing, and tourism. One of the main reasons for the popularity of Maslow's hierarchy of needs is probably its simplicity. Maslow argues that if none of the needs in the hierarchy were satisfied, then the lowest needs, the physiological ones, would dominate behavior. If these were satisfied, however, they would no longer motivate, and the individual would move up to the next level in the hierarchy, safety needs. Once these were satisfied, the individual would move up to the next level, continuing to work up the hierarchy as the needs at each level were satisfied.

Maslow's theory has received little clear or consistent support from research evidence. Some of Maslow's propositions are totally rejected, while others receive mixed and questionable support. Witt and Wright (1992) criticize the theory for not including several important needs, perhaps because they do not fit conveniently into Maslow's hierarchical framework. Such needs are dominance, abasement, play, and aggression. They prefer Murray's (1938) classification scheme, suggesting that from the point of view of tourist motivation it provides a much more comprehensive list of human needs that could influence tourist behavior. Murray listed a total of fourteen physiological and thirty psychological needs, from which it is possible to identify factors that could influence a potential tourist to prefer or avoid a particular holiday. However, due to its complexity, Murray's work is not as easy to apply as Maslow's hierarchy, and has therefore not been adopted by tourism researchers.

Other attempts to explain tourist motivation have identified with Maslow's needs hierarchy. Mill and Morrison (1985), for example, see travel as a need or want satisfier, and show how Maslow's hierarchy ties in with travel motivations and the travel literature. Similarly, Dann's (1977) tourism motivators can be linked to Maslow's list of needs. He argued that there are basically two factors in a decision to travel, the push factors and the pull factors. The push factors are those that make you want to travel and the pull factors are those that affect where you travel. In his appraisal of tourism motivation, Dann proposed seven categories of travel motivation:

1. Travel as a response to what is lacking yet desired. We live in an anomic society and this, according to Dann, fosters a need in people for social interaction that is missing from the home environment.

2. Destination pull in response to motivational push, already discussed.

3. Motivation as a fantasy.

4. Motivation as a classified purpose, such as visiting friends and relatives or study.

5. Motivational typologies, which will be studied in depth later in this chapter.

6. Motivation and tourist experiences.

7. Motivation as auto-definition and meaning, suggesting that the way tourists define their situations will provide a greater understanding of tourist motivation than simply observing their behavior.

Crompton (1979) agreed with Dann, as far as the idea of push and pull motives was concerned. He identified nine motives, seven classified as sociopsychological or push motives and two classified as cultural or pull motives. The push motives were escape from a perceived mundane environment, exploration and evaluation of self, relaxation, prestige, regression; enhancement of kinship relationships, and facilitation of social interaction. The pull motives were novelty and education. Crompton identified these motives from a series of in-depth interviews with a group of people and found that the push motives were difficult to uncover. He pointed out that people may be reluctant to give the real reasons for travel if those reasons are deeply personal or intimate.

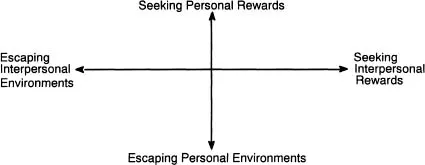

Mannel and Iso-Ahola (1987) identify two main types of push and pull factors, personal and interpersonal. They suggest that people are motivated to travel to leave behind the personal or interpersonal problems of their environment and to obtain compensating personal or interpersonal rewards. The personal rewards are mainly self-determination, sense of competence, challenge, learning, exploration, and relaxation. The interpersonal rewards arise from social interaction (see Figure 1.2).

Krippendorf (1987), in an enlightening book on tourism, sees a thread running through all these theories of tourism motivation. First, travel is motivated by “going away from” rather than “going toward” something; second, travelers’ motives and behavior are markedly self-oriented. The author classifies these theories into eight explanations of travel: recuperation and regeneration, compensation and social integration, escape, communication, freedom and self-determination, self-realization, happiness, and travel broadening the mind.

FIGURE 1.2. The Escaping and Seeking Dimensions of Leisure Motivation

Source:Mannel and Iso-Ahola, 1987.

The tourist motivation model proposed by Plog (1974) has been one of the most widely cited. According to Plog, travelers may be classified along two dimensions: allocentrism/psychocentrism and energy. Travelers who are more allocentric are thought to prefer exotic destinations, unstructured vacations rather than packaged tours, and more involvement with local cultures. Psychocentrics, on the other hand, are thought to prefer familiar destinations, packaged tours, and “touristy” areas. Later, Plog added energy, which describes the level of activity desired by the tourist; high-energy travelers prefer high levels of activity while low-energy travelers prefer fewer activities.

Plog's findings evolved from syndicated research for airline companies that were interested in converting nonflyers into flyers (recently the airlines have taken to giving a free experimental flight to nonflyers!). He found that the majority of the population were neither allocentric nor psychocentric, but “midcentric"—somewhere in the middle. It has been argued, however, that Plog's theory is difficult to apply as tourists will travel with different motivations on different occasions (Gilbert, 1991). There are many holidaymakers who will take a winter skiing break in an allocentric destination, but will then take their main holiday in a psycho-centric destination.

Smith (1990) has also criticized the model. Using data from seven nations, he tested the model's basic hypothesis as well as its applicability to other countries. He concluded that his test of the allocentric/psychocen-tric model failed to support the hypothesized association between personality types and destination preferences. He even criticized tourism researchers for relying on untested hypotheses for explanations about how the tourist system works.

TYPOLOGIES OF TOURISTS

Besides Plog, other tourism researchers have tried to explain tourist recreational behavior by developing typologies of tourist roles. Most are based on empirical data obtained from questionnaires and/or personal interviews. One of the first—Cohen (1972)-—proposed four classifications of tourists: (1) the organized mass tourist, highly dependent on the “environmental bubble,” purchasing all-inclusive tours or package holidays; (2) the individual mass to...