eBook - ePub

Introducing Persons

Theories and Arguments in the Philosophy of the Mind

- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Stimulating introduction to the most central and interesting issues in the philosophy of mind. Topics covered include dualism versus the various forms of materialism, personal identity and survival, and the problem of other minds.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Introducing Persons by Peter Carruthers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Philosophy History & TheoryPART ONE:

MYSELF AND OTHERS

1 THE PROBLEM OF OTHER MINDS

i. The Problem

The problem of other minds consists in an argument purporting to show that we can have no knowledge of any other conscious states besides our own. Our task in this section will be to build up this argument in a number of different stages.

If the conclusion of the argument were correct, then I could not be said to know that the human beings around me are, in the strict sense, persons. Although I should see them walking and talking, laughing and crying, I should not be able to know that they have thoughts, have feelings, are amused or upset, and so on. All I should be able to know is that there are certain living organisms which physically resemble myself, which move around and behave in characteristic ways, and which are the source of complicated patterns of sound which I call ‘speech’.

(A) The Reality of the Problem

Many will be inclined to dismiss the problem out of hand. Since they are completely certain that other minds do exist, they will insist that there must be something wrong with an argument which makes our knowledge of them seem problematic. Either one of the premises must be false, or the argument itself must be invalid. But notice that there have been many periods throughout history when people would have been equally dismissive of any argument suggesting that we cannot have knowledge of the existence of God. They too would have insisted that since they were completely certain of God's existence (‘Everybody knows it!’) there must be something wrong with the argument somewhere. Yet many of us would now think that they were wrong.

The general point is that it is possible to be subjectively certain of a belief without actually having any adequate reason for holding it. One's certainty may have causes but no justification. For example, there may have been causal explanations of people's certainty about the existence of God, either of a sociological sort (‘People believe what others believe’) or of a psycho-analytical sort (‘People need to believe in a father-figure’ ). Similarly, our certainty about the existence of other minds may serve some biological or evolutionary function, without any of us really having adequate reason for believing in any conscious states besides our own. It is no good anyone beating the table shouting ‘But of course I know!’ If they think they know, then they should take up the challenge presented by the problem of other minds, and show us how they know.

It is no good complaining, either, that the whole attempt to raise a problem about the existence of other minds must be self-defeating, because of the use made of the terms ‘our’ and ‘we’ It is true that the use of these terms does strictly presuppose the existence of other minds besides my own. But then it is not really necessary that I should make use of them. The whole argument giving rise to the problem of other minds can be expressed in the first-person singular throughout. I can present this argument to myself, and you (if there really are any of you) can present it to yourselves. At no point does it need to be presupposed that there really are a plurality of us.

(B) A Preliminary Statement of the Problem

As a way into the problem of other minds, ask yourself the question ‘How do I know that what I see when I look at a red object is the same as what anyone else sees when they look at a red object?’ That is: how do I know that our experiences are the same? Perhaps what I see when I look at a red object is what you see when you look at a green object, and vice versa. The point is: we naturally assume that we call objects by the same names ( ‘red’, ‘green’, etc.) in virtue of having the same experiences when we look at those objects; but it could equally well be the case that we have different experiences, but the difference never emerges because we call those experiences by different names.

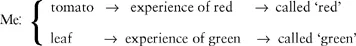

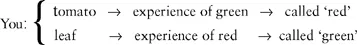

So how do you know that the situation is not as follows: what I see when I look at a red object (e.g. a tomato) is what you see when you look at a green one (e.g. a leaf) and vice versa; but because the experience I call ‘red’ is the experience you call ‘green’ , and vice versa, we always describe the colours of the objects in the same way. Diagrammatically:

Thus when I look at a red object I have an experience of red which I refer to as ‘red’; but when you look at a red object you have an experience of green, which you refer to as ‘red’ So we both say that the object is red.

In order to get yourself into the feel of what is going on here, stare intently at a brightly coloured object, immersing yourself in its colour, and ask: ‘How do I know that any other person has this?’, referring not to the colour of the object itself, but to your immediate experience of the colour. Does it not seem that it would only be possible for you to know that another person has this sort of experience if you could look into their minds, thus in some sense having, or being aware of, their experience? But this is logically impossible. I cannot be aware of your experiences, because anything which I am immediately aware of is, by definition, my own experience. Even if two Siamese twins feel pain in exactly the same place (the place where they join) they do not feel one another's pain. On the contrary, each feels their own. So it appears impossible that I should ever know whether or not anyone else has the sort of experience which I have when I look at a red object.

(A remark here about telepathy, or ‘mind-reading’ If such a thing can occur, then there would be a sense in which it is possible to have awareness of the thoughts, if not the experiences, of another person. For I might then be able to know what you are thinking, while you are thinking it, without having to ask you, or otherwise infer it from your behaviour. All the same I should not be able to have the sort of immediate awareness of your act of thinking which you have yourself. What would happen might be this: I suddenly think ‘That person is thinking such-and-such’, and find that I generally get it right. Or perhaps a thought pops into my mind unbidden, accompanied by the belief that my act of thinking this thought is somehow caused by your act of thinking an exactly similar thought; and again I generally get it right. But either way, telepathy can only provide me with knowledge of other people's thoughts if I have some independent way of checking my inituitive, telepathically induced, beliefs. So telepathy, even if it occurs, cannot provide a solution to the problem of other minds. For it is only if I have some other way of discovering what other people are thinking, that I could ever discover that my telepathic beliefs about their thoughts are generally correct.)

It begins to seem that I cannot know exactly what sorts of experiences other people have. But now: how do I know that they have any experiences at all? How do I know, when they utter the word ‘red’ on being confronted with a red object, that there is really any intervening experience? And how do I know, when other people cry and scream when they are injured, that there is any intervening pain? For why cannot the light entering their eyes, or the injury, just bring about those sorts of behaviour directly? The point is: all that I ever see, or have direct knowledge of, are other people's circumstances and behaviour. I can observe the input (injury), and observe the output (crying). But what entitles me to infer that there exists any intervening conscious experience? It would seem that the inference cannot be a valid one. For as everyone admits, there is always the possibility of pretence. Since it is possible to writhe and scream (and even have a genuine injury) without actually feeling any pain, the inference from the former to the latter cannot be valid.

As expounded thus far, the argument giving rise to the problem of other minds might be summarised as follows:

(1) It is impossible to have direct awareness of the mental states of another human being.

(C1) So our knowledge of such states (if it exists) must be based upon inference from observable physical states.

(2) Because of the ever-present possibility of pretence, no such inference can ever be valid.

(C2) So (from (C1) and (2)) it cannot be reasonable to believe in the mental states of other human beings.

Premiss (1) appears to be obviously true. I surely cannot experience another person's experiences. I cannot, as it were, ‘look into’ their minds. I can only, in that sense, ‘look into’ my own, by introspection. Premiss (2) also appears true. No matter what behaviour a human being exhibits, there are possible worlds in which they exhibit such behaviour without possessing any conscious experiences. So everything appears to turn on the validity of the two steps, to (C1) and to (C2).

(C) Perceptual Knowledge

The validity of the move to (C1) might certainly be challenged. For it depends upon the suppressed premiss that there are only two modes of knowledge, namely immediate awareness and inference. But this is false. There is a third mode of knowledge, namely observation (or perception). Thus when there is a tomato on the plate in front of me, I obviously do not have the kind of immediate awareness of it which I have of my pains, when I have them; for the tomato is not itself an experience of mine. But then neither do I have to infer that the tomato is there on the basis of anything else. Rather I observe that it is there: I see it. Now we do in fact very often say such things as ‘I saw that she was in pain, so I called the doctor.’ So perhaps our knowledge of the existence of other minds is not knowledge by inference, nor knowledge by immediate awareness, but knowledge by perception.

Now I think it might be acceptable to say that we sometimes know of other people's mental states by observation, if there were no problem of other minds, or if we had somehow solved that problem. It will be possible to perceive that someone is in pain if, but only if, one already knows on other grounds the sorts of behaviour which generally have pains as their cause. For although we do not, in ordinary life, normally infer —deduce, reason out — that someone is in pain on the basis of their behaviour, our claim to observe that they are suffering will only be justified given a particular background of empirical assumptions, amongst which will be the claim that behaviour of that sort is regularly correlated with pain.

The general point is that what you perceive is partly a function of what you have reason to believe. As it is sometimes said: perception is theory-laden. Thus if you know yourself to be on a Hollywood film-set then you will perceive, not buildings, but artificial frontages of buildings; even though your experiences may be indistinguishable from the experiences you would be having if you were standing in front of real buildings. Similarly an engineer might truly say ‘I saw that the bridge was in danger of collapsing’, where an ordinary person could only say ‘I saw that the bridge was sagging in the middle’

Consider this example: two people are standing in front of a building. The one reasonably (but falsely) believes themself to be on a Hollywood set. The other knows this to be a genuine building, with a back as well as a front. Now although there may be a sense in which both undergo the same experiences, it is surely clear that only one of them perceives a building. The other merely perceives the front of a building. Similarly then: consider two people observing a third who is obviously injured, and is writhing and screaming. Only one of them knows that this sort of behaviour is regularly correlated with pain. Then only one of them will perceive that the person is in pain. The other will merely perceive the behaviour.

Thus it will only be possible to perceive the mental states of other persons if we already possess a certain amount of background knowledge: for example that injury followed by screaming is regularly correlated with pain. But now, how are we supposed to have discovered that these correlations exist? We discovered that a falling barometer is regularly correlated with rain, by observing that when the barometer falls it often rains soon afterwards. But this required us to have independent access to the states of the two kinds: one can observe the rain independently of observing the falling barometer. But as we noted above we do not, and cannot, have any direct access to the mental states of other persons, independently of our access to their behaviour.

I conclude that we can only perceive the mental states of other persons if we can know such general truths as that writhing and screaming are regularly correlated with pain. But since these general truths cannot themselves be known on the basis of perception, it cannot be perception of the mental states of others which provides the solution to the problem of other minds. The argument as far as (C1) has thus been sustained: if we have knowledge of the mental states of others, it must ultimately be based upon inference from observable physical states.

(D) Knowledge by Analogy

The move from (C1) and (2) to (C2) is also invalid as it stands. From the fact that no description of someone's behaviour can ever validly entail a description of their mental state, it does not follow that the one cannot provide good reason to believe the other. There are two possibilities here. Firstly, such arguments may contain a suppressed premiss. For instance if we put together a description of someone's behaviour with the claim that behaviour of that sort is regularly correlated with pain, then these do now entail that the person in question is (very likely) in pain. But this is where we were a moment ago: how could we ever have discovered that there are general correlations between certain kinds of behaviour and certain kinds of mental state? For we never have direct access to other people's conscious states.

It might be replied that there is at least one case in which I have direct access to both behavioural and mental states, and that is my own. So can I not discover the empirical correlations in my own case first, and then reason outwards to the case of other people? This would be a form of inductive (as opposed to deductive) argument. This now gives us our second possibility: although an argument from descriptions of behaviour to descriptions of mental states may not be deductively valid, it may nevertheless be a reasonable inductive step, founded upon my knowledge of the correlations which exist in my own case.

So the proposal before us is this: I first of all discover in my own case that when I am physically injured this often causes me pain, which in turn causes me to cry out. I then reason inductively that since other people, too, can be injured, and since when they are they generally display similar behaviour to myself, that there is very likely a similar intervening cause. Namely: a pain. But ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part One: Myself and Others

- Part Two: Immaterial Persons

- Part Three: States of Mind

- Part Four: Material Persons

- Retrospect

- Bibliography of Collected Papers

- Glossary

- Index