![]()

A definitive moment in the history of the moving image was the discovery, in 1824, by the Englishman Peter Roget that, if a series of drawings of an object were made, with each one showing the object in a slightly different position, and then the drawings were viewed in rapid succession, the illusion of a moving object was created. Roget had discovered what we now call ‘the persistence of vision’, the property whereby the brain retains the image of an object for a finite time even after the object has been removed from the field of vision. Experimentation showed that, for the average person, this time is about a quarter of a second, therefore if the eye is presented with more than four images per second, the successive objects begin to merge into one another. As the rate increases, the perception of motion becomes progressively smoother, until, a t about 24 drawings per second, the illusion is complete.

It is intriguing to consider that, had the chance evolution of the human eye not included this property, then today we would be living in a world without cinemas, TV sets or computer screens and the evolution of our society would have taken an entirely different course!

Early Cinematography

With the discovery of the photographic process in the 1840s, experimentation with a series of still photographs, in place of Roget’s drawings, soon demonstrated the feasibility, in principle, of simulating real-life motion on film. During the next fifty years, various inventors experimented with a variety of ingenious contraptions as they strove to find a way of converting feasibility into practice. Among these, for example, was the technique of placing a series of posed photographs on a turning paddle wheel which was viewed through an eyehole - a technique which found a use in many ‘What the butler saw’ machines in amusement arcades.

Thomas Edison (Figure 1.1) is generally credited with inventing the machine on which the movie camera was later based. Edison’s invention - the Kinetoscope, patented in 1891 - used the sprocket system which was to become the standard means of transporting film through the movie camera’s gate.

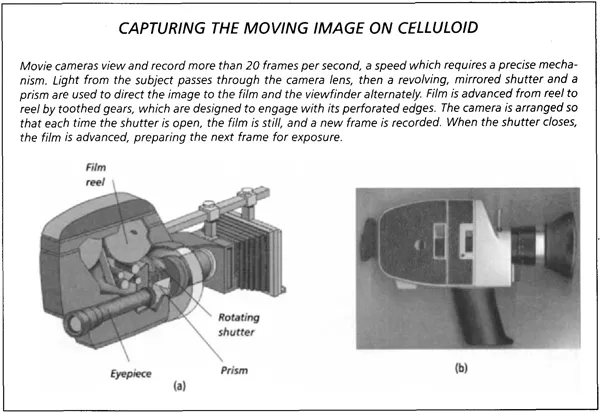

After several years of development, the movie camera (Figure 1.2), and the projector which was based on the same sprocket and gate mechanism, were ready for production of the first commercial silent films in the United States in 1908 (Figure 1.3). The earliest film-making activities were based on the east coast, but by 1915 Hollywood on the west coast was already emerging as film capital of the new industry and, by 1927, the Warner Brothers Hollywood studio released the first major talking film - The Jazz Singer, starring Al Jolson - to an enthusiastic public.

Figure 1.2 (a) Exploded view shows the basic mechanism of the movie camera based on Edison’s 1891 invention, (b) A scan of the home movie camera which I bought in Vermont in 1969 and which still uses the same basic mechanism

Figure 1.3 Scene from an early silent movie

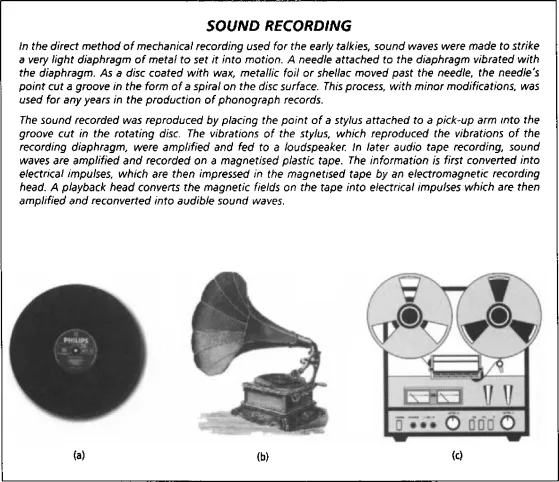

The process of recording sound on magnetic tape (Figure 1.4) was as yet unknown and the early sound films used a process known as Vitaphone, in which speech and music were recorded on large discs which were then synchronized with the action on the screen, sadly displacing the many piano players who had made their living by providing an imaginative musical accompaniment to the silent films.

Figure 1.4 (a) An old 78 rpm disc, now consigned to the museum; (b) an early phonograph and (c) a tape deck

As film audiences grew, the movie makers turned their attention to methods of filming and projecting in colour and, by 1933, the Technicolor process had been perfected as a commercially viable three-colour system. Becky Sharp was the first film produced in Technicolor, in 1935, being quickly followed by others, including one of film’s all-time classics, The Wizard of Oz, just as war was breaking out in Europe.

While others developed the techniques which used real-life actors to portray the characters in a movie, Walt Disney pioneered the animated feature-length film, using a technique which derived directly from Roget’s work nearly a hundred years earlier. Using an early form of storyboarding and more than 400,000 hand-drawn images he produced Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (Figure 1.5), based on Grimm’s fairy tale, in 1937. As we shall see later, computer animation owes much to the techniques developed by the Disney Studios over the last sixty years.

Figure 1.5 Snow White - a Disney classic

Television

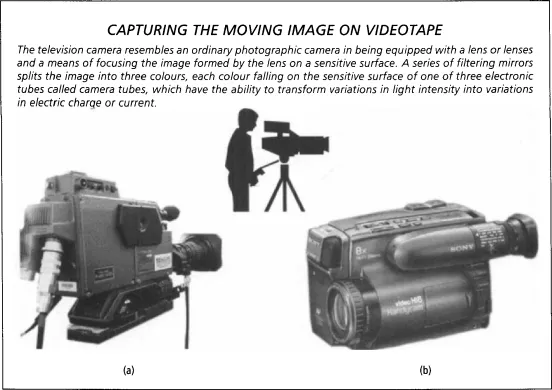

The first experimental television took place in England in 1927, but it was not until the late 1940s that television began to challenge the popularity of the cinema. Unlike the movie camera, the TV camera builds up an image of a scene by sweeping a beam of electrons across the screen of camera tube (Figure 1.6). The scanning of a single image is called a field, and the horizontal and vertical scan rates are normally synchronous with the local power-line frequency. Because the world is generally divided into 50 Hz and 60 Hz electrical power frequencies, television systems use either 50 field or 60 field image-scanning rates. The television broadcasting standards now in use include 525 lines, 60 fields in North America, Japan, and other US-oriented countries, and 625 lines, 50 fields in Europe, Australia, most of Asia, Africa, and a few South American countries.

Figure 1.6 (a) A TV camera, (b) The Sony camcorder – employing a CCD detection system – which I use for recording the usual family events

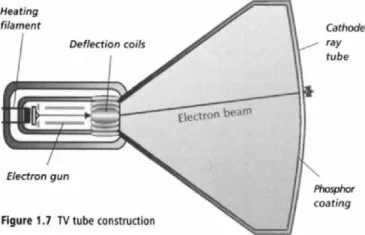

The advantage of scanning with an electron beam (Figure 1.7) is that the beam can be moved with great speed and can scan an entire picture in a small fraction of a second. The European PAL (Phase Alternate Line) system uses the 625 horizontal line standard, i.e. to build up a complete ‘frame’ the beam scans the image 625 times as it moves from the top to the bottom, and continues to do this at a frequency of 25 frames per second. The number of picture elements in each line is determined by the frequency channels allocated to television (about 330 elements per line). The result is an image that consists of about 206,000 individual elements for the entire frame.

Figure 1.7 TV tube construction

The television signal is a complex electromagnetic wave of voltage or current variation composed of the following parts: (1) a series of fluctuations corresponding to the fluctuations in light intensity ot the picture elements being scanned; (2) a series of synchronizing pulses that lock the receiver to the same scanning rate as the transmitter; (3) an additional series of so-called blanking pulses; and (4) a frequency-modulated (FM) signal carrying the sound that accompanies the image. The first three of these elements make up the video signal. Colour television is made possible by transmitting, in addition to the brightness, or luminance, signal required for reproducing the picture in black and white, a signal called the chrominance signal, which carries the colour information.

Whereas the luminance signal indicates the brightness of successive picture elements, the chrominance signal specifies the hue and saturation of the same elements. Both signals are obtained from suitable combinations of three video signals, which are delivered by the colour television camera, each corresponding to the intensity variations in the picture viewed separately through appropriate red, green, and blue filters. The combined luminance and chrominance signals are transmitted in the same manner as a simple luminance signal is transmitted by a monochrome television transmitter.

Like the picture projected on to the cinema screen, the picture which appears on the domestic television screen depends upon the persistence of vision. As the three colour video signals are recovered from the luminance and chrominance signals and generate the picture’s red, blue, and green components by exciting the phosphor coatings on the screen’s inner surface, what the eye sees is not three fast moving dots, varying in brightness, but a natural full-frame colour image.

To prevent the flicker which can occur with a frame rate of thirty frames per second, ‘interlacing’ is used to send every alternate horizontal scan line 60 times a second. This means that every 1/60th of a second, the entire screen is scanned with 312½ lines (called a field), then the alternate 312½ lines are scanned, completing one frame, reducing flicker without doubling transmission rate or bandwidth.

Although computer monitors operate by the same principles as the television receiver, they are normally non-interlaced as the frame rate can be increased to sixty frames per second or more since increased bandwidth is not a problem in this case.

Emergence of the VCR and the Camcorder

Virtually all early television was live – with original programming being televised at precisely the time that it was produced – not by choice, but because no satisfactory recording method except photographic film was available. It was possible to make a record of a show – a film shot from the screen of a studio monitor, called a kinescope recording – but, because kinescope recordings were expensive and of poor quality, almost from the inception of television broadcasting electronics engineers searched for a way to record television images on magnetic tape.

The techniques which were developed to record images on videotape were similar to those used to record sound. The first magnetic video tape recorders (VTRs) (Figure 1.8), appeared in the early 1950s, with various alternative designs evolving through the 1960s a...