![]()

Part 1

Your English Language Learner

Tony Erben University of Tampa

with

Bárbara C. Cruz Stephen J. Thornton University of South Florida

![]()

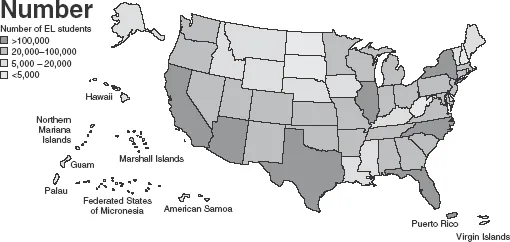

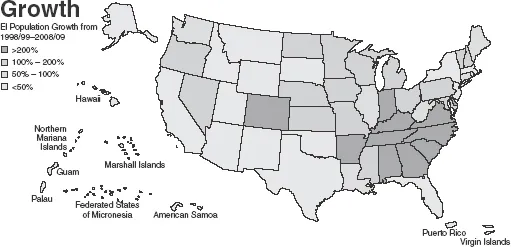

English language learners (ELLs) represent the fastest-growing group at all levels of schooling in the United States. (We will use the term “English language learner” throughout the book, mostly because of its widespread use and acceptance, although the term “English learner” is increasingly being used.) The U.S. Census Bureau (2010a) reports that between the years of 1980 and 2007 the percentage of non-English language speakers in the United States increased by 140 percent. (Figure 1.1 shows the number of ELLs in the United States and Figure 1.2 shows the growth.) As a result, the number of ELLs in the nation's schools has more than doubled (National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition, 2006). In several states, including Texas, California, New Mexico, Florida, Arizona, North Carolina, and New York, the percentage of ELLs within school districts ranges anywhere between 10 and 50 percent of the school population. In sum, there are over 10 million ELLs in U.S. schools today. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2010b), one out of five children aged 5 to 17 years old speaks a language other than English at home. Although many of these children and adolescents are heritage language learners (those exposed to a language other than English at home) and are proficient in English, many others are recent immigrants with barely a working knowledge of the language, let alone a command of academic English. Meeting their needs can be particularly challenging for all teachers given the often text-dependent nature of content areas. The language of the curriculum is often abstract and includes complex concepts requiring critical reading and thinking skills. Additionally, many ELLs do not have a working knowledge of American culture that is necessary for understanding key social studies concepts or that can serve as a schema for new learning.

But let's now look at these ELLs. Who are they and how do they come to be in our classrooms?

ELL or, sometimes, English learner, is the term used for any student in an American school setting whose native language is not English. Their English ability lies anywhere on a continuum from knowing only a few words to being able to get by using everyday English. But they still need to acquire academic English so that they can succeed educationally at school. All students enrolled in an American school, including ELLs, have the right to an equitable and quality education.

FIGURE 1.1. The number of English language (EL) learners in the United States.

Source: National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition, 2011.

FIGURE 1.2. The growth of the English language (EL) learner population in the United States between 1998/1999 and 2008/2009.

Source: National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition, 2011.

Traditionally, many ELLs were placed in stand-alone English to speakers of other languages (ESOL) classes and learned English until they were deemed capable of following the regular curriculum in English in a mainstream classroom.

However, with the introduction of federal and state legislation such as the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, Proposition 227 in California, and other English-only legislation in other states, many school systems started requiring that ELLs receive their English instruction through their curriculum content classes rather than through stand-alone ESOL classes.1 This “mainstreaming” approach has become the most frequently used method of language instruction for ELL students in U.S. schools. Mainstreaming involves placing ELLs in content-area classrooms where the curriculum is delivered in English; typically, curricula and instruction are not modified in these classrooms for non-native English speakers (Carrasquillo & Rodriguez, 2002). According to Meltzer and Hamann (2005), placement of ELLs in mainstream classes occurs for a number of reasons, including assumptions by non-educators about what ELLs need, the scarcity of ESOL-trained teachers relative to demand, the growth of ELL populations, the dispersal of ELLs into more districts across the country, and restrictions in a growing number of states regarding the time ELLs can stay in ESOL programs. ELL specialists (e.g., Coady et al., 2003) predict that, unless these conditions change, ELLs will spend their time in school with: (1) teachers inadequately trained to work with ELLs; (2) teachers who do not see meeting the needs of their ELLs as a priority; and (3) curricula and classroom practices that are not designed to target ELLs’ needs. As we shall see, of all possible instructional options to help ELLs learn English, placing an ELL in a mainstreamed English-medium classroom where no accommodations are made by the teacher is the least effective approach. It may even be detrimental to the educational progress of ELLs.

But have the thousands of curriculum content teachers across the United States, who now hold the collective lion's share of responsibility in providing English language instruction to ELLs, had adequate preservice or in-service education for the task? Are they able to modify, adapt, and make the appropriate pedagogical accommodations within their lessons for this special group of students? Affirmative answers to these questions are essential if ELLs are to make academic progress commensurate with grade-level expectations. It is also important that teachers feel competent and effective in their professional duties.

The aim of Part 1 of this book is to provide an overview of the linguistic mechanics of second language development. Specifically, as teachers you will learn what to expect in the language abilities of ELLs as their proficiency in English develops over time. Although the rate of language development among ELLs depends on the particular instructional and social circumstances of each ELL, general patterns and expectations will be discussed. We will also outline the learning outcomes teachers might expect in what ELLs typically accomplish in differing ESOL programs as well as the importance of maintaining first language development. Because school systems differ across the United States in the ways in which they try to deal with ELL populations, we describe the pedagogical pros and cons of an array of ESOL programs. We also clarify terminology used in the field. In addition, Part 1 profiles various ELL populations that enter U.S. schools (e.g. refugees vs. migrants, special needs) and shares how teachers can make instruction more culturally responsive. Finally, we survey what teachers can expect from the cultural practices that ELLs bring to the classroom and ways in which both school systems and teachers can enhance home–school communication links.

![]()

1.2

The Process of English Language Learning and What to Expect

It is generally accepted that anybody who endeavors to learn a second language will go through specific stages of language development. According to some second language acquisition theorists (e.g., Krashen, 1981; Pienemann, 2007;), the way in which language is produced under natural time constraints is very regular and systematic. Pienemann's (1989, 2007) work has centered on one subsystem of language, namely morphosyntactic structures, that is, a given language's linguistic units such as words, parts of speech, or intonation. It gives us an interesting glimpse into how an ELL's language may progress (Table 1.1). Just as a baby needs to learn to crawl before it can walk, so too a second language learner will produce language structures only in a predetermined psychological order of complexity. What this means is that an ELL might utter “homework do” before being able to utter “tonight I homework do” before ultimately being able to produce a target-like structure such as “I will do my homework tonight.” Of course, within terms of communicative effectiveness, the first example is as successful as the last example. The main difference is that one is less English-like than the other.

Researchers such as Pienemann (1989, 2007) and Krashen (1981) assert that there is an immutable language acquisition order and, regardless of what the teacher tries to teach to the ELL in terms of English skills, the learner will acquire new language structures only when he or she is cognitively and psychologically ready to do so. Even still, teachers can very much affect the rate of language development and acquisition by providing what is known as an “acquisition-rich” classroom. Ellis (2005), among others, provides useful research generalizations that constitute a broad basis for “evidence-based practice.” Rather than repeat them verbatim, here we synthesize them into five principles for creating effective second language learning environments. They are presented and summarized below.

TABLE 1.1 Generalized patterns of ESOL development stages

Stage | Main features | Example |

1 | Single words; formulas | My name is ___________.

How are you? |

2 | Subject–verb object word order; plural marking | I see school

I buy books |

3 | “Do”-fronting; adverb preposing; negation + verb | Do you understand me?

Yesterday I go to school.

She no coming today. |

4 | Pseudo-inversion; yes/no inversion; verb + to + verb | Where is my purse?

Have you a car?

I want to go. |

5 | 3rd person –s; do-2nd position | He works in a factory.

He did not understand. |

6 | Question-tag; adverb–verb phrase | He's Polish, isn't he?

I can always go. |

Source: Pienemann (1988).

ESOL, English to speakers of other languages.

Principle 1: Give ELLs Many Opportunities to Read, to Write, to Listen to, and to Discuss Oral and Written English Texts Expressed in a Variety of Ways

Camilla had only recently arrived at the school. She was a good student and was making steady progress. She had learned some English in Argentina and used every opportunity to learn new words at school. Just before Thanksgiving her civics teacher commenced a new unit of work on the executive branch of the federal government. During the introductory lesson, the teacher projected a photo of the president sitting to the right of his advisory cabinet on the whiteboard. She began questioning the students about the members of the executive branch. One of her first questions was directed to Camilla. The teacher asked, “Camilla, tell me what you see on the right hand side of the cabinet.” Camilla answered, “I see books and pencils.”

Of course the teacher was referring not to the cabinet which is next to the whiteboard, but to the cabinet projected on to the whiteboard. Though a simple mistake, the example above is illustrative of the fact that Camilla has yet to develop academic literacy.

Meltzer (2001) defined academic literacy as the ability of a person to “use reading, writing, speaking, listening and thinking to learn what they want/need to learn AND [to] communicate/demonstrate that learning to others who need/want to know” (p. 16). The definitio...