![]()

Postural Control in Children: Implications for Pediatric Practice

Sarah L. Westcott

Patricia Burtner

Sarah L. Westcott is Adjunct Associate Professor at Drexel University, Programs in Rehabilitation Sciences, Philadelphia, PA, and a staff physical therapist at the Lake Washington School District, Redmond, WA, and Northwest Pediatric Therapies, Issaquah, WA. Patricia Burtner is Associate Professor at University of New Mexico, Occupational Therapy Programs, Albuquerque, NM.

Address correspondence to: Sarah L. Westcott, PT, PhD, 5019 218th Avenue NE, Redmond, WA 98053 (E-mail:

[email protected]).

SUMMARY. Based on a systems theory of motor control, reactive postural control (RPA) and anticipatory postural control (APA) in children are reviewed from several perspectives in order to develop an evidence-based intervention strategy for improving postural control in children with limitations in motor function. Research on development of postural control, postural control in children with specific motor disabilities, and interventions to improve postural control is analyzed. A strategy for intervention to improve postural control systems at the impairment and functional activity levels based on a systems theoretical perspective is presented. Suggestions for research to improve evidence for best practice are provided.

[Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <[email protected]> Website: <http://www.HaworthPress.com> © 2004 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.] KEYWORDS. Reactive postural adjustments, anticipatory postural adjustments, children, physical therapy, occupational therapy

INTRODUCTION

Movement is a core feature of our being human. Through movement, we care for ourselves and express our feelings and desires. We generally perform movements with ease and dexterity, yet the act of moving is incredibly complex and somewhat vulnerable as evidenced by the existence of movement disorders. Due to the complexity of movement generation and in an effort to understand the etiology of movement disorders, we have sought to find ways to break down the act of moving into components that we can measure, analyze, and apply to intervention. For instance, movement can be broken down into the components for generating and executing the “primary” or desired movement and the components for the background postural movement necessary to support that prime movement (Massion, 1992). Massion (1992) compares a motor act to an iceberg, with the goal oriented movement being the apparent ice and the postural related component of the movement being the hidden ice. Controversy exists as to whether postural and prime movements should be considered separately, however, recent studies have supported the existence of separate neural control mechanisms for postural and primary movements (Aruin, Shiratori, & Latash, 2001; Slijper, Latash, & Mordkoff, 2002). Postural movement has also been demonstrated to be a basic ability and critical link for producing coordinated movement (Katic, Bonacin, & Blazevic, 2001) and one that is lacking in many pediatric movement disorders (Westcott, 2001). Tests and measures have been created to examine postural control (Westcott, Richardson, & Lowes, 1997) and many prominent intervention methods emphasize the facilitation of postural control (Westcott, 2001).

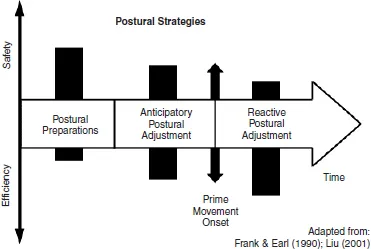

Postural control for movement involves the orientation of the body in space for stability as well as orientation to the task within the context of the environment (Massion, 1994). At times the body is controlled at rest (static equilibrium) and other times with movement (dynamic equilibrium). Postural control can be defined simply as the ability to control one’s center of mass (COM) over the base of support (BOS) (Horak, 1992). It can be broken down into several units as depicted in Figure 1. These units hypothetically vary in their safety vs. efficiency effect as characterized in Figure 1. Two of these units will be considered in detail in this paper, the control mechanisms for reacting to unexpected external postural perturbations, reactive postural adjustments (RPA), and those for anticipating internal postural perturbations related to production of voluntary movement, anticipatory postural adjustments (APA). An example of a RPA is the response that occurs to keep the body balanced when someone bumps into you. An APA example is the postural activity that precedes and links with a reach forward while standing so that you do not lose your balance and the movement is completed smoothly and accurately.

FIGURE 1. Components of postural strategies presented along a time and efficiency scale. Earlier postural preparations are safer but not as efficient in terms of producing coordinated movements. Anticipatory postural adjustments, occurring within 100 msec of the prime movement onset, are more efficient than postural preparations and assist in the coordination and safety of the prime movement activity. Reactive postural adjustments occur after the prime movement or in reaction to external perturbations, within 80-100 msec, and are very efficient in facilitating postural control. (Adapted from Frank & Earl, 1990; Liu, 2001)

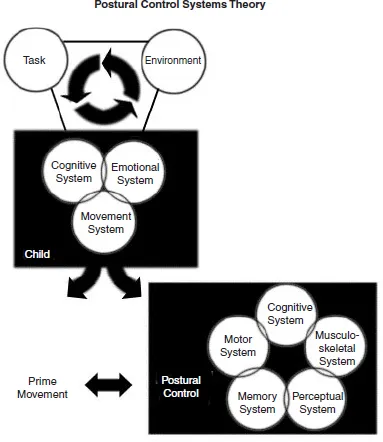

Applying a general systems theory of motor control, within both RPA and APA, there are several systems that coordinate to produce effective postural control (Bernstein, 1967; Horak, 1992). At least three systems, sensory, motor, and musculoskeletal, participate in coordinating postural activity. The sensory system cues the individual that there has been a perturbation and/or gives feedback for adjustments during slow movements and after movements in regard to how successful the postural activity generated has been. The motor system organizes and cues the appropriate activation of the muscles. The musculoskeletal system provides the framework on which we move and creates the forces to produce the postural muscle activity. The state of any of these systems affects the overall postural activity and in a sense may control the output. Other systems can also have an effect on the postural activity observed. For instance, the directions given to the individual, or the behavioral state and alertness of the individual may vary the postural activity (Burleigh & Horak, 1996; Burleigh, Horak, & Malouin, 1994; Nashner, 1982). Likewise the environment and task can cause the individual to vary postural activity (Thelan & Spencer, 1998). Figure 2, which depicts postural control from a systems theory perspective, provides the conceptual framework for this article.

The purpose of this paper is to summarize research on postural control (RPA and APA) in children and to present intervention strategies based on our summary. First, we review research on development of RPA and APA. Next we analyze the available research on RPA and APA in children with and without motor disabilities. Then, based on our research, we discuss the evidence for interventions to improve postural control and present an intervention strategy for children with motor disabilities. We have taken the liberty to make suggestions that potentially follow from the research, but also may overstep the specific research evidence. We have done this deliberately to generate discussion and encourage further research.

DEVELOPMENT OF RPA AND APA

Incorporating research from the fields of neuroscience and biomechanics, our understanding of the development of postural control is based on the development of neural and musculoskeletal systems. Three processes critical to underlying postural mechanisms have been identified as: (1) motor processes: the emergence of neuromuscular response synergies which maintain stability of the neck, trunk and legs, (2) sensory processes: the development of visual, vestibular and somatosensory systems, as well as the maturation of central sensory strategies organizing outputs from these senses for body and limb orientation, and (3) musculoskeletal components: changes in structural and soft tissue morphology, muscle strength development, and range of motion which includes the biomechanical linkage of body segments for movement (Shumway-Cook & Woollacott, 2001). These systems develop in a non-linear fashion at different rates. Postural control in the child emerges when development of each system reaches the threshold necessary to support the specific motor behavior (Thelan, 1986). Thus, knowledge of the development of each system is important for determining which system may be rate limiting. Through identification of the system(s) that are rate limiting, the therapist is able to formulate an intervention plan specific to the needs of the individual child. Table 1 A-D details the developmental progression for each system for RPA and APA.

FIGURE 2. Postural control components based on a systems theory of motor control. The task, environment and child represent systems affecting movement. Within the child, the movement system can be divided into the control components for the prime movement and postural control. Within postural control, the sensory, motor and musculoskeletal systems work in concert with other systems to produce efficient and safe postures and recovery of postures. These three systems have been examined to some extent in children with and without disabilities. (Adapted from Horak, 1991; Liu, 2001)

In the research summarized in Table 1, a common paradigm used to determine the RPA is to place the child on a moveable platform and translate the platform in anterior or posterior directions to produce external perturbations (Nashner, 1976) (see Figure 3). The child can be supine, prone, sitting or standing on the platform. Typically electromyographic (EMG) recordings are used to determine the muscle coordination patterns used and kinematics are recorded to analyze specific body movements. The center of pressure (COP) or center of gravity (COG) position changes of an individual can also be recorded from force plates to document RPA during any type of external perturbation or APA during any type of voluntary movement (Liu, 2001) (see Figure 4). RPA changes due to sensory input differences have been examined using a sensory organization test consisting of six conditions which systematically alter the visual and somatosensory input to determine if a person over-relies on or has decreased registration of a particular sensory input to maintain balance (Horak, Shumway-Cook, & Black, 1988) (see Figure 5). Readers are encouraged to refer to the studies referenced throughout this paper to fully understand the methods.

TABLE 1A. Typical Development of Postural Control: Musculoskeletal System (Mattiello & Woollacott, 1997; Shumway-Cook & Woollacott, 2001; Woollacott & Shumway-Cook, 1994)

Components | Age of maturation to adult-like capacity |

Force production (Breniere & Bril, 1998; Lin, Brown, & Walsh, 1994; Roncesvalles & Jensen, 1993; Roncesvalles, Woollacott, & Jensen, 2001; Schloon, O’Brien, Scholten & Prechtl, 1976; Sundermier, Woollacott, Roncesvalles & Jensen, 2001) | 2 months–force generation against gravity in neck muscles when tilted in prone and supine 6 months (pre-pull-to-stand infants)–force generation adequate to sustain body weight Under 1 year age–low force production capability is a constraint for sitting and standing 9 months-10 years (developing through life)–overall torque production to recover balance after sudden perturbation increases; peak torque at the ankle and hip increased as distance and time to complete COP readjustments decreased; newly standing and walking infants have smaller torque values than older children who are able to skip and gallop Postural capacity to control balance with leg muscles may not be complete until 4-5 years of walking experience |

Range of Motion | Developing through the teen years; Should not be a constraint until elderly |

Body Geometry (Jensen & Bothner, in press; McCollum & Leen, 1989; Woollacott, Roseblad, & von Hofsten, 1988) | Different ages–changes rapidly during growth spurts dependent on gender and hormonal development Infants–increased body mass in head, arms, and trunk segments as compared to older children and adults 12-15 months–increased upper body mass results in faster sway during perturbed stance 4-9 years–kinematics of body sway similar to adults 12-15 years through adults–gradual decrease in sway velocities |

To summarize, for RPA, there appear to be innate patterns of muscle coordination organized for head control, sitting balance and standing balance. There also appear to be periods in development where infants and children become more disorganized and regress to immature muscle co-contraction patterns to potentially reduce the degrees of freedom they need to control. With experience and practice, these co-contractions decrease, allowing more flexible and adaptable RPA. There appears to be a stage-like RPA development with disorganization in standing postura...