- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Archaeological evidence suggests that Neolithic sites had many different, frequently contradictory functions, and there may have been other uses for which no evidence survives. How can archaeologists present an effective interpetation, with the consciousness that both their own subjectivity, and the variety of conflicting views will determine their approach.Because these sites have become a focus for so much controversy, the problem of presenting them to the public assumes a critical importance. The authors do not seek to provide a comprehensive review of the archaeology of all these causewayed sites in Britain; rather they use them as case studies in the development of an archaeological interpetation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ancestral Geographies of the Neolithic by Mark Edmonds in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Settings and scenes

Landscape and history

Hambledon Hill. A chalk dome with three great spurs that rises between Child Okeford and Shroton in Dorset. Cretaceous. Marine life made geology by pressure and time. Crows wheel above slopes that shift in and out of focus, artefacts of mist and changes in the light. Giant furrows fold back upon the rise and on each other, sinuous earthworks that follow the contour, turning up in places to cross the ridge. Drawn along these lines, the eye is pulled, like centuries of soil, down folds and slopes to lower ground, to the Vale of Blackmoor and Cranborne Chase. The view is a familiar one. It is a patchwork of fields and hedgerows, of hamlets, villages and more isolated farms. Ash trees caught in hedges hold the line of old boundaries in their boughs. Beech stands turn to copper and bronze each autumn, catching fire in the low sun of late afternoon. There is even a yew wood, dark and dense against the green. Some consider the wood to be haunted. Ghosts walk in stories that resonate around the hill, only to be lost with increasing distance. The stories are local; tethered to the land.

Like the earthworks on the hilltop, much of this scene appears timeless. For Thomas Hardy, who stumbled in the mists on Hambledon in the 1890s, the land was a constant. The Wessex he created was an old country, one in which ‘…the busy outsider's ancient times are only old: his old times are still new; his present is futurity.’ The land had stability and depth and this seemed condensed in the prehistoric monuments that lay scatttered across its surface: barrows, stone circles and great chalk banks; ruins already scarred by collectors and by scientific interest. These features are a powerful presence in his novels. They lend a mythic weight to the human stories that he tells, hinting that the forces driving his protagonists are just as old and changeless. At times it is as if the land itself determines human nature and their destiny.

Reworked in more recent writing and through landscape portraiture, this nostalgic image of an almost timeless rural world remains powerful. The land is something to gaze upon, to appeal to and to own. A constant in the England of advertising and in the empty rhetoric of certain politicians, it remains an icon. Used to sell everything from butter to foreign policy, it is stable and reassuring, a foundation for some of our origin myths of national identity. Looked at more closely, the scene has a past which cuts against the grain of those myths. It is a surface inhabited over millennia, variously worked and changed by people. Lines of hawthorn and ash follow the edges of medieval tracks and fields, enclosing land where old furrows survive as soil marks. Other hedges are the imprint of more recent hands, boundaries set in the last two centuries. There are other traces too. Seen from the air, the land is etched with the marks of prehistory: places of settlement and ceremonial and of dead long since forgotten; sites revealed when the plough brings its varied crop of pottery and stone to the surface.

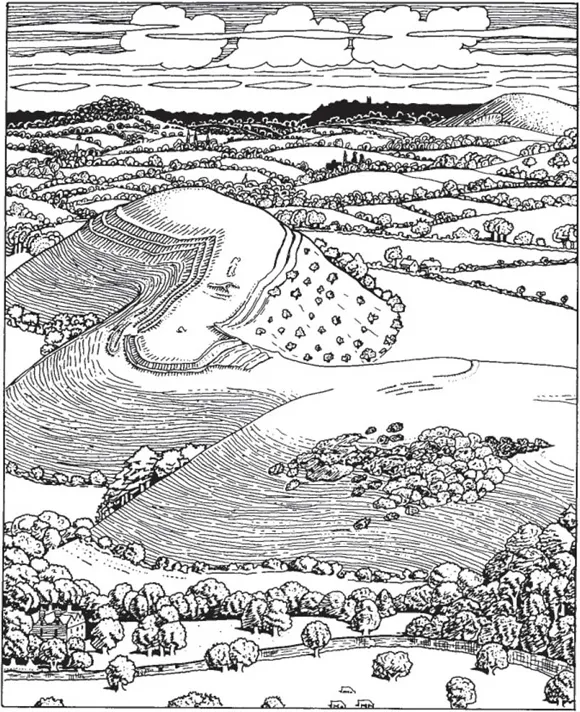

Figure 1 Hambledon Hill, Dorset. (After Heywood Sumner.)

Time and change are also inscr ibed on the hill itself; a duration acknowledged in Heywood Sumners’ plan from 1911. Beneath the trig point that ties it to the geometry of the modern are older and more varied features. There are fields and marl pits only a few centuries old, evidence for grazing and cultivation that continue to this day. Anglo-Saxon burials have also been identified. Bodies were laid to rest in older banks that looked down upon a land where both kinship and kingship were important concerns. Older still are the earthworks of an Iron Age hill-fort, turf-covered ramparts that once were white. Another, Hod Hill, lies on an adjacent crest. Developed in the centuries around the Roman occupation, the hill-fort dominated the skylines and the consciousness of those who lived and worked on lower ground. Associated with the Durotriges, it was a place of occupation and of periodic gatherings, a statement cut deep into the chalk. Softened now by a mantle of grass, it has remained a point of reference. Even now, the parish boundary between Child Okeford and Shroton runs through the hill-fort and along the eastern inner rampart. The place is also remembered for its use in the ‘pitchfork rebellion’, when local relations were recast by the upheavals of the Civil War.

The line goes further. The ‘old camp’ reoccupied by the Clubmen of 1645 was itself a reworking of the hill. Those who lived and assembled during the Iron Age acknowledged older features and other pasts. There are Bronze Age barrows on the crest, perhaps even settlement and cultivation, and there are older barrows still; two earlier Neolithic long mounds, respected as people cut ditches or set platforms in the chalk. These mounds were older than a hundred generations by the time the first ramparts were raised, and yet they were recognised, given space within the boundaries and in the flow of later life across the hill. A similar respect was shown to the earthworks of enclosures as old as these mounds, low banks and ditches that crown the hill and its spurs. Diminutive now and best seen in low light, the line of these older features seems to have inspired the position of some of the later earthworks.

The hill has been used and understood in many ways over time. It has been at the centre and on the margins of things, a place of gatherings and burial, of settlement, cultivation and bold gestures. Despite the stability it seems to embody, it is not a constant. The same can be said of the land that falls away on every side. Permanent though they seem to us, the features that we cherish today are products of social and political geographies very different from our own.We don't have to go that far back. Many hedgerows belong to a time when land once held as common was consolidated in the hands of a few by piecemeal and parliamentary enclosure. Estates that cash-cropped sheep on old commons and fields recast traditional patterns of residence and labour. There was a break with older, customary geographies, one which did not serve the interests of all. Writing in Northamptonshire in the eighteenth century, John Clare demonstrated that many of these changes were far from uncontested. For him, as for those who challenged new rents or worked to breach new hedges and ditches, enclosure changed the land.

There once were lanes in nature's freedom dropt,

There once were paths that every valley wound—

Inclosure came, and every path was stopt;

Each tyrant fix’d his sign where paths were found,

To hint a trespass now who cross’d the ground:

Justice is made to speak as they command;

The high road now must be each stinted bound:

Inclosure, thou’rt a curse upon the land,

and tasteless was the wretch who thy existence plann’d.

There once were paths that every valley wound—

Inclosure came, and every path was stopt;

Each tyrant fix’d his sign where paths were found,

To hint a trespass now who cross’d the ground:

Justice is made to speak as they command;

The high road now must be each stinted bound:

Inclosure, thou’rt a curse upon the land,

and tasteless was the wretch who thy existence plann’d.

Clare romanticised the past that came before enclosure. He said little of the inheritance of older ways of living and working or of older tensions: seigneural relations; duties to markets, state and church; or the moral and obligatory ties that stretched back and forth between communities. It was enough that some were threatened. Yet it is a quality of his poetry that it highlights the local, everyday, consequences of developments usually discussed at a more general scale. What he tells us is that the land was not a static backdrop to the events and processes of his time. It lay at the heart of social life. Inhabited and reworked at both local and regional scales, it was an artefact of history. His writing is also important in another way. Passionate and situated, it clashes with many contemporary images of landscape found in the paintings and literature commissioned by members of ‘polite’ society. It reminds us that ways of living through and even thinking about landscape were as political as they were practical.

Approaching Neolithic monuments

So far as we know, Clare never visited Hambledon, yet his observations take us to the heart of what makes the hill and places like it so remarkable. Often difficult to recognise and always difficult to comprehend, the accumulated earthworks that survive are both the medium and the outcome of relations between people in the past. They were created in step with the understandings that people had of their worlds, of who they were and of their relations with others: personal, familial, communal, political; identities and authorities bound up in the practical facts of living and in moments of performance or observance. The hill tells us something else as well. Patterns in the playing out of earthworks suggest that these monuments were often objects of thought, caught up in the pattern and purpose of people's lives long after they were constructed. What they may have meant to much later generations is not always clear. Traces of heroic pasts, fashioned in myth to serve particular interests. Part of the land itself, acknowledged only in passing and in moments of reflection. Forgotten altogether, only to be rediscovered and accorded new values. Hambledon reminds us that the past was not a neat succession of periods, opening and closing like the chapters of a book, each one characterised by a distinctive set of traits. The playing out of relations between people involved the piecemeal inheritance, abandonment and rediscovery of the past as it appeared in their present.

That, of course, is easily said. It is easy to assert that material traditions— patterns of life and labour—are intimately bound up in the reproduction of the social world. It is rather more difficult to flesh out those ties, to chart their articulation, or to follow how they changed. Even when we study comparatively recent history, the task is far from easy. It is hard to capture the spirit of the time when the Clubmen gathered, or when rights of access sustained over generations were cut by new forms of ownership and new loyalties. These histories are complex, contradictory and close grained.They resist being grasped in any one account and are often obscured by the very concepts or scales of analysis that we use. More often than not history gives way to process; local currents of identity and authority are lost in the flow of grander narratives. These problems are compounded the further back in time that we go. As centuries become millennia, our evidence changes in character and in material detail. Familiar landmarks fade from view and it becomes all the more difficult to establish contexts and points of reference. Under these circumstances, the broadest processes often come to dominate accounts.

Nowhere is this problem more acute than in our attempts to ‘make sense’ of some of the earliest features on the hill. Conventionally assigned to the early fourth millennium BC, the long mounds and enclosures of the earlier Neolithic are traces of a world very different from today. We are certainly not the first to interpret that world, but it is customary nowadays to be quite circumspect. We talk of a time when people had begun to experiment with stock and crops, when ancestors were a powerful presence in the land, a time when life was bound to a seasonal wheel and to webs of kinship, descent and local renown. Yet for all of our disciplinary rigour and our technical accomplishment, it is a difficult world to capture; fragmentary and elusive.

Our difficulties with the earlier Neolithic in Britain stem from many sources. To begin with, the inception of the period shifts back and forth between models of indigenous development and colonisation during the later fifth and early fourth millennia. Debate has been made all the more complex by the lack of good radiocarbon dates for the horizon separating the Neolithic from its predecessor, the Mesolithic. Further problems arise because this transition also marks the meeting point between different traditions of enquiry. The two periods have generally been studied by different groups of scholars, each with their own perspectives and priorities. This division of labour has become so entrenched that we often seem to forget that the two periods are rationalisations, developed by us to make sense of our evidence.

This confusion has been compounded by the fact that our definitions of the term ‘Neolithic’ have been far from constant. Some use the term to talk of definitive traits such as farming, that are independent of time and space, others use it to denote a specific historical process, and it is not uncommon for people to shift back and forth between the two. Originally a label attached to a stage in a general evolutionary scheme, the passage of time saw the term come to denote a cultural phenomenon, marked by a distinctive repertoire of sites and artefacts, some of which have continental parallels. Talk of Neolithic cultures has, in its turn, given way to a view of the period as an economic entity, associated with a switch from hunting and gathering to food production. More recently still, interest has shifted towards a view of the period as a time that saw the development of new ways of thinking about land, people and even time itself.

What else do we commonly say about the earlier Neolithic? We bracket it with radiocarbon and talk of its persistence for about a thousand years. Dates are often imprecise, but it is common to draw a line between around 4000 and 3000 BC. We also talk about it as a time which saw changes in material traditions; the first appearance of pottery and the first widespread use of polished stone tools. Like domesticated plants and animals, these are common features in discussion. More often than not, we talk about the ceremonial monuments that appear in the early fourth millennium: long mounds associated with the remains of the dead and enclosures with interrupted and irregular ditches; mines, quarries or the long parallel banks of cursus monuments.Varied in character, chronology and distribution, these places are prominent in many accounts.

This fascination with monuments has taken many forms and it persists for many reasons. These are places that have endured. Although many have been eroded by time and the plough, there are still enough upstanding earthworks to catch the eye and the imagination. Many are also enigmatic. Their persistence confronts us with a sense of deep time; form and content revealing an otherness or difference that is always just beyond our grasp. Often associated with fragmentary human remains, with evidence for feasting and other forms of ceremonial, they hint at ways of living and thinking that jar with the present. Qualities once evoked by Hardy, these themes are now crucial to what are often casually dismissed as ‘alternative’ views. Yet there is more here than just a desire for difference, romanticism or nostalgia. The simple persistence of many of these monuments often reflects a considerable and protracted expenditure of effort. This in itself means little enough. Unmodified features can be accorded spiritual or historical significance, and this may have been important at the time. However, the character and scale of places like tombs and enclosures suggests that many occupied prominent positions in the social and symbolic landscapes of the early fourth millennium.

How do we understand these places? For some, long mounds and enclosures are an expression of a cultural change, a product of the arrival of new people and/or new ideas. On occasion, they have been seen as a direct consequence of the development of agriculture. For others, the scale of particular monuments has been read as an index of social complexity, investment of effort a reflection of the authority achieved or inherited by a few at the time. Recently, the focus has been at a more intimate scale, reflecting a concern with the changing meanings of these places and the events they witnessed. Here it is common to find a view of monuments as frames upon which social memories and values could be inscribed. Work on tombs has recognised that the ways people made sense of death lay at the heart of their ways of thinking about themselves and their relation to the world around them. Studies of other monuments have also acknowledged that in the earlier Neolithic, as elsewhere, ritual and public ceremonial was crucial to the reproduction of certain forms of authority. For many, the power of various rites was to some extent derived from their enactment within and around the monuments that we can still see today.

These ideas have taken research in many directions. There is now a rich and varied literature on the roles that monuments played in the earlier Neolithic, and on the character and significance of ceremonies conducted within their bounds. A lot of work has been done on long mounds and megaliths, on enclosures and ceremonial ways. We have explored acts of construction, offerings and rituals, and movement in and around the places of death, ancestry and initiation. Latterly, we have begun to trace the ways in which processions and formal patterns of movement link ritual sites across the landscape. In doing so, at least some of the lines drawn between orthodox and alternative perspectives have been eroded. Crucial to much recent research has been the idea that people do not think about their world in the abstract, or even gaze at it like some painting in a frame. Rather, they experience it physically. They move around, go in and out of places, they congregate and they disperse. They can go in certain directions but not others. They can go to certain monuments, but only when the time is right. Boundaries and pathways, places of secrecy or danger, formal and informal settings, backstage and frontstage and places in between all help to shape the world of ritual experience. Much of what happens in these times and places is constituted by the past, by real or invented tradition and by what is already there. Through what some have called a ‘technology of memory’, people absorb, reuse and rework the past through their physical encounter with particular monuments and performative or ritual events.

These shifts of perspective have been valuable, but our descriptions can still seem disappointingly thin. To say that the earlier Neolithic lasts about a thousand years is one thing. To talk of that time as a span of around forty to fifty generations is quite another. It suggests that at least some traditions were remarkably persistent and we should ask why that might be. Also, it reminds us that while monuments and ritual can be central to the ways in which societies remember, they are far from monolithic. Their meanings and their roles can change, just as they may vary from one setting to another. The fact that some were worked and reworked over centuries suggests that this is likely to have been the case.

There are other qualities to monuments that we sometimes miss. A great many accounts look only at their role in the reproduction of political hierarchies. There is a preoccupation with chiefs or regional elites, and rather less discussion of the broader social landscapes in which particular monuments were set. Questions of hierarchy are, of course, important. Forms of authority were present at most places and times and we need to understand how they were reproduced. But we should also consider those other themes that may have animated life in the past: categories based on family and kin affiliation, on gender, and on all the different grades of child- and adulthood. These identities are difficult to grasp, but many would have been brought into sharp relief during events at monuments. People's senses of who they were and what was expected of them would shape and be shaped by their participation in rituals going on around them. And this participation and understanding would not remain static.What could be done or said, where a person could or could not go, would change according to context and audience, as people got older, were initiated, became married or widowed.

This idea takes us beyond monuments themselves. Whilst acknowledging their power and the drama of ritual performance, we have to work between these settings and the landscapes of the everyday. Unless we explore the conditions under which people came together at important times and places, we cannot begin to understand the particular purposes they served. We cannot ask how rituals were woven into cycles of routine experience, and we miss how routine itself was caught up in social reproduction.

It is here that we encounter problems in both conventional and more avant-garde archaeological writing. Discussions of daily and seasonal life and of feast days and ritual are separated by changes in the questions we ask and the imposition of rigid divisions: Sacred and Profane; Ceremonial and Everyday; Public and Domestic. Brought into play in the study of sites and artefacts, these divisions are also mapped out across regions. We maintain a distinction between sacred landscapes and the secular spaces of settlement and subsistence. This imbalance can be traced in a contrast of writing. The times and places of overt ritual are often explored through a rich and subtle vocabulary. Memory and movement are brought into focus, as are people and artefacts, and ways of speaking and acting can seem highly charged. This is often justified, but discussions of living and work...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Ancestral Geographies of the Neolithic

- Illustrations

- Preface

- 1: Settings and scenes

- 2: Origins

- 3: Ancestral geographies

- 4: Keeping to the path

- 5: Working stone

- 6: A gift from the ancestors

- 7: The living and the dead

- 8: Attending to the dead

- 9: A time and a place for enclosure

- 10: Drawing the line

- 11: Arenas of value

- 12: The pattern of things

- 13: Changes in the land

- 14: Post excavation

- Postscript

- Bibliography