- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cognition In Action

About this book

This revised textbook is designed for undergraduate courses in cognitive psychology. It approaches cognitive psychology by asking what it says about how people carry out everyday activities: how people organize and use their knowledge in order to behave appropriately in the world in which they live.; Each chapter of the book starts with an example and then uses this to introduce some aspect of the overall cognitive system. Through such examples of cognition in action, important components of the cognitive system are identified, and their interrelationships highlighted. Thus the text demonstrates that each part of the cognitive system can only be understood properly in its place in the functioning of the whole.; This edition features increased coverage of neuropsychological and connectionist approaches to cognition.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Recognising Faces: Perceiving and Identifying Objects

It is a busy Saturday afternoon in your town. The streets are swarming with shoppers pushing and shoving. You are trying to find a pair of shoes you like and wondering why on earth you didn’t do your shopping midweek when things were quieter. In the distance, you notice two people walking towards you. The one on the left you recognise immediately as your grandmother; the one on the right you do not recognise.

What could be a more commonplace and everyday occurrence than recognising the face of someone you know? We do it all the time—at home, at work, watching television, in town. “But”, asks the cognitive psychologist, “How do we do it? How do we recognise the lady approaching us as granny? What processes go on in our minds that allow us to identify the lady on the left as familiar while rejecting the person on the right as unfamiliar?” Person and face recognition must be a matter of achieving a match between a perceived stimulus pattern and a stored representation. When you get to know someone, you must establish in memory some form of representation or description of his or her appearance. Recognising the person on subsequent occasions requires the perceived face to make contact with the stored information, otherwise the face will seem unfamiliar.

As cognitive psychologists try to develop a more specific account of recognising a person, problems start to arise. What form does the internal representation of a familiar face take? How are seen faces matched against stored representations? How does seeing a familiar face trigger the wider knowledge you have about that person, including his or her name? When you see a familiar person, he or she is often moving against a complex visual background: How does your visual system isolate elements of the whole visual scene as constituting one object (a person) moving in a particular way at a particular speed? These are some of the questions a complete theory of visual processing should be able to answer, and some of the questions that are addressed in this chapter. We use face recognition in this chapter to introduce some of the important questions about how we perceive and recognise objects in general, not just faces. We will consider both the general issue of how we recognise objects, including people, and the more specific questions concerning how we recognise people we know.

RECOGNISING FAMILIAR PATTERNS

There are lots of faces visible in the shopping crowd in our example, but you recognise only one of them. How? A ploy commonly adopted by cognitive psychologists when trying to understand how the mind performs a particular task is to ask how we could create an artificial device capable of performing the same task. How could we, for example, program a computer to recognise a set of faces and reject others?

First of all, the computer would need to somehow memorise the set of faces it had to recognise. It would then need to compare each face it saw (through a camera input, for example) with the set stored in memory to see if there was a match. If a satisfactory match was achieved, the face would be “recognised”; if not, it would be rejected as unfamiliar.

Now, within those broad outlines, there are a number of options available regarding the possible nature of the representation of each face to be stored in memory and the manner in which the perceived face could be compared against the stored set. The stored set of faces could form a set of templates, with the new face being matched to each template and recognition occurring when a complete or nearly complete match of template and pattern took place. Perhaps recognising a particular face would require the stimulation of a particular pattern of cells within the retina of the eye. Different patterns of stimulation would be stored for each known face. Pattern recognition systems along these lines have been used for many years in, for example, the mechanical reading of the numbers upon bank cheques.

Template mechanisms of pattern recognition are relatively simple to set up. However, they have serious limitations which suggest that they are not the mechanism used by the human perceptual system when recognising familiar objects. Problems arise as soon as there is any change in the original stimulus. For example, if you see your grandmother from a different distance to that for which the template was set up, then a smaller or larger image will be projected onto the retina of your eye and will stimulate a different set of cells. Similar problems arise if you see your grandmother from an angle different to that for which the template was created. Also, people change in their appearance—their hairstyles, their spectacles, their faces age, and so on. While such changes can cause us problems in recognition, we do normally still identify our acquaintances. However, the mismatch with any template would be sufficient for it to fail to be selected.

Template-based systems of pattern recognition can be elaborated. They can, for example, include more than one template, so that common views of the same object can be recognised. Face recognition might include templates for views of the full face, threequarter (portrait) and profile angles. There is evidence that cells in the brains of monkeys are differen-tially sensitive to such alternative views (Perrett et al., 1984). It is possible to “normalise” a new pattern until it is a standard size and orientation before it is matched to the templates. Some theorists of face recognition have considered template accounts (e.g. Ellis, 1975). However, most researchers have looked to more sophisticated ways in which the information about known objects and people might be matched to a newly experienced pattern.

One alternative might be the storing of the description of a person’s face in terms of a list of features (a feature being a property of an object that helps discriminate it from other objects). Granny’s face might then be held in memory as a feature list something like:

- white hair

- curly hair

- round face

- hooked nose

- thin lips

- blue eyes

- round gold-rimmed spectacles

- wrinkles

and so on. The features of each face to appear before the camera could then be compared against the stored list. If all features agreed, then the face would be recognised as granny’s, but if the person before the camera had, say, a long, thin face rather than a round one, it would be rejected as unfamiliar. This would be a feature-based model of recognition. One of the advantages of such models is that they do not tightly specify how the features go together as is the case with template models. For example, the same set of features can be recognised from many different views of the same face.

There is no denying that features play a role in face recognition, or that some features are more important than others. In free descriptions of unfamiliar faces, subjects utilise features, mentioning the hair most often, followed by eyes, nose, mouth, eyebrows, chin, and forehead in that order (Shepherd, Davies, & Ellis, 1981). As faces become familiar, there is evidence of a decreasing reliance on external features such as hairstyle, colour and face shape towards a reliance on the internal features of eyes, nose and mouth (Ellis, Shepherd, & Davies, 1979). This may be because hairstyle in particular can change, and so is a relatively unreliable cue to recognition, whereas internal features are comparatively stable and reliable.

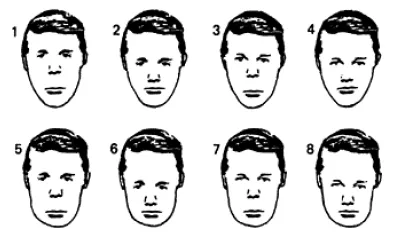

The problem with any simple feature-based model is illustrated by Fig. 1.1. A “scrambled” face contains the same features as a normal face, but their configuration has been altered. Although it may be possible to recognise the scrambled face of a wellknown person, it is much harder than recognising a normal face. Also, as Fig. 1.2 shows, varying the configuration of a fixed set of features can substantially alter the appearance of the face. So, while template models may be too specific about the details of each face, a simple feature list model would not be specific enough. A satisfactory model of face recognition will take into account the configuration of the features but will be sufficiently flexible that it can recognise the same face despite the patterns actually experienced varying considerably, because the person is being seen from one of many possible angles or distances.

FIG. 1.1 The scrambled face of a wellknown person illustrates the importance of configuration in pattern recognition. Reproduced with permission from Bruce and Valentine (1985).

You will be beginning to appreciate the challenge faced by object and person recognition systems, whether our own or those that might be created, for example, to allow robots to behave like humans as they do in science fiction stories. Such recognition in a world of moving, changing objects is very difficult. However, the challenge is greater still than we have discussed so far. How do we even manage to perceive an object as an object? We will consider this even more basic question in the next section.

FIG. 1.2 Each pair of faces (1 and 2; 3 and 4; 5 and 6; 7 and 8) differ only in the configuration of their internal features. Adapted with permission from Sergent (1984).

SEEING OBJECTS

Your grandmother is moving through a crowd of shoppers carrying a couple of bags. Parts of her periodically disappear from view when she passes behind a bench seat, or when another shopper passes in front of her. Your visual system is confronted with a kaleidoscope of patches of light of different colours, reflecting off surfaces of objects at varying distances, moving in varying directions at varying speeds. What you perceive, however, is a coherent scene composed of distinct objects set against a stable background. This unified impression is the end-product of processes of visual perception which psychologists have sought to understand.

Some of the first psychologists to be interested in how we perceive one part of a visual display as belonging with another were the German Gestalt psychologists. From 1912 onwards, Gestalt psychologists, led by Wertheimer and his students Kohler and Koffka, concentrated upon the way in which the world we perceive is almost always organised as whole objects set against a fixed background. Even three dots on a page (see Fig. 1.3) will cohere as a triangle. Our perceptual systems are organised to derive forms and relationships from even the simplest of inputs. The Gestalt psychologists argued that our perceptual systems have evolved to make object perception possible. They set out to describe the principles that the perceptual system uses to group together the elements in the perceptual field. Subsequently, those attempting to model object perception (e.g. Marr, 1982) have incorporated these principles into their models, as we describe later in the chapter.

FIG. 1.3. Three simple dots on a page cannot but be seen as a triangle.

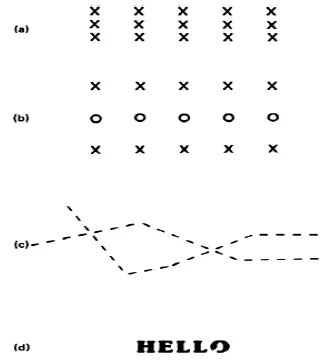

FIG. 1.4 Examples of Gestalt principles in action. (a) Proximity: the arrangement of the crosses causes them to be perceived as being in columns rather than rows. (b) Similarity: the similarity of the elements causes them to be perceived as being in rows rather than columns. (c) Good continuity: causes you to interpret this as two continuous intersecting lines. (d) Closure: the gap in the “O” is perceptually completed.

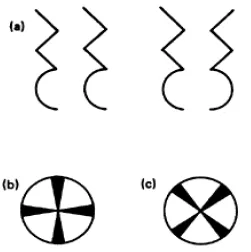

The Gestalt psychologists formulated several principles to describe the way in which parts of a given display will be grouped together (see Fig. 1.4a). However, grouping is modified by the similarity of components. So, in Fig. 1.4b, the noughts and crosses tend to be seen in lines because they are similar. In Fig. 1.4c, the lines of dashes are seen as crossing one another, rather than meeting at a point turning at an angle and moving away. This illustrates the Gestalt principle of good continuation, which maintains that elements will be perceived together where they maintain a smooth flow rather than changing abruptly. In a similar way, the perceptual system will opt for an interpretation that produces a closed, complete figure rather than one with missing elements. Sometimes this can lead to the overlooking of missing parts in a familiar object. If you had not been primed to look for it by the text, it would be easy to conceptually complete the word and overlook the gap in one of the letters in Fig. 1.4d. Other perceptual preferences highlighted by the Gestalt psychologists were for bilaterally symmetrical shapes (e.g. Fig. 1.5a). Other things being equal, the smaller of two areas will be seen in the background, and this is enhanced by them being in a vertical or horizontal arrangement (see the black and white crosses in Figs 1.5b and c).

FIG. 1.5 (a) Organisation by lateral symmetry. The symmetrical form on the right is much more easily perceived as a coherent whole than the asymmetrical form on the left. (b) The preference here is to perceive the smaller area as the figure and the larger area as the ground, i.e. as a black cross on a white background. (c) If the larger areas is to be perceived as the figure (i.e. a white cross on a black background), then orienting the white area around the horizontal and vertical axes makes this easier.

To summarise their principles, Wertheimer proposed the Law of Pragnanz. This states that, of the many geometrically possible organisations that might be perceived from a given pattern of optic stimulation, the one that will be perceived is that possessing the best, simplest and most stable shape. Sometimes, the input can be interpreted in more than one way and the result is a dramatic alternating in our perception. The face-vase illusion (Fig. 1.6) devised by the Gestalt psychologist Rubin is a well-known example. The information in the picture allows it to be interpreted either as a vase or as two faces. When the interpretation shifts, the part that had been the figure becomes the background, and vice versa.

Although we have illustrated the Gestalt principles using very simple examples and illustrations, their application to normal, intricate visual processing is in the way they assist the visual system to unite those components of the visual array that constitute single objects. There are other cues that assist in this unification. All the cues discussed so far apply to stationary objects, but additional cues arise wh...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Introduction

- 1 Recognising Faces: Perceiving and Identifying Objects

- 2 Reading Words: Sight and Sound in Recognising Patterns

- 3 Telling Sheep from Goats: Categorising Objects

- 4 Reaching for a Glass of Beer: Planning and Controlling Movements

- 5 Tapping Your Head and Rubbing Your Stomach: Doing Two Things at Once

- 6 Doing Mental Arithmetic: Holding Information and Operations for a Short Time

- 7 Answering the Question: Planning and Producing Speech

- 8 Listening to a Lecture: Perceiving, Understanding or Ignoring a Spoken Message

- 9 Witnessing an Accident: Encoding, Storing and Retrieving Memories

- 10 Celebrating a Birthday: Memory of Your Past, in the Present and for the Future

- 11 Arriving in a New City: Acquiring and Using Spatial Knowledge

- 12 Investigating a Murder: Making Inferences and Solving Problems

- 13 Diagnosing an Illness: Uncertainty and Risk in Making Decisions

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Cognition In Action by Alan F. Collins,Philip Levy,Peter E. Morris,Mary M. Smyth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.