1 The economy in the fifteenth century

Preconditions for European expansion

Paola Massa

An integrated economic system: Europe in the fifteenth century

The geographical background

Geographers describe Europe, or the Old Continent as it is sometimes called, as a large indented peninsula extending for thousands of kilometres seawards. This circumstance has had a decisive effect on Europe’s climate and greatly influenced the lives of its people, motivating them to navigate, explore and colonize new lands. Over the course of centuries the internal territorial divisions of Europe have undergone considerable variations as a result of numerous wars and subsequent political changes. However, despite their impact and influence, and despite enduring political divisions, economically we can consider fifteenth-century Europe as a single unit, as a community united by similar, or at least complementary, interests.

The French historian Fernand Braudel identified a process of integration in the economic fabric of Europe, occurring between the Middle Ages and the modern period, and he took the Old Continent as the basis for a model of economic development that he defined as a ‘world system’ or ‘world economy’.1 In his model, the population was subdivided into different social groups. These had differing demands for goods and manufactured products, and were largely self-sufficient for their requirements; thus they did not recognize any great economic advantage, or chance of enough profit, in exchanges with other groups beyond their boundaries. A further interesting aspect of Braudel’s development model of modern Europe is how the territory and economy of the Old Continent ultimately came to include not only the whole Mediterranean area, but also the North African countries that had economic links with it. The waters of the ‘internal’ sea of the Mediterranean were an important point of intersection for the movement of goods, precious metals and people.

This idea of Europe is one that embraces an economic world with physical boundaries, limited by mountain chains, the North Pole and the African desert. It is a view of Europe that perhaps we can still look to today as we reflect on its political and cultural characteristics and historical traditions.

Urban poles of development and markets

An important aspect of the ‘world economy’ model in its application to fifteenth century Europe2 is the way it underlines the dynamic changes that lead to successive and increasingly advanced stages of development. Braudel argued that a number of urban centres emerged, which he defined as ‘poles’, and which provided ‘leadership’ at different times. It was under their motivating force that certain sectors of the economy were expanded and formed bodies that, in different periods of history, acted as nuclei attracting greater numbers of productive resources, because of the more advantageous operating conditions.

At least until the mid-fifteenth century, apart from the textile industry (particularly the manufacturing of woollen cloth), it was in commerce where good profits could be made. Commerce, which could be called ‘commercial capitalism’, had existed since the early thirteenth century. Marco Cattini has described it as ‘the merchant acting as middleman between producer and consumer and closing the great gap in time and space that lay between the place where certain goods were acquired and where they were sold’.3 Merchants were men with considerable financial means and credit, and were considered reliable. They had a close technical knowledge of their wares in addition to being well versed in commerce, law and accounting.

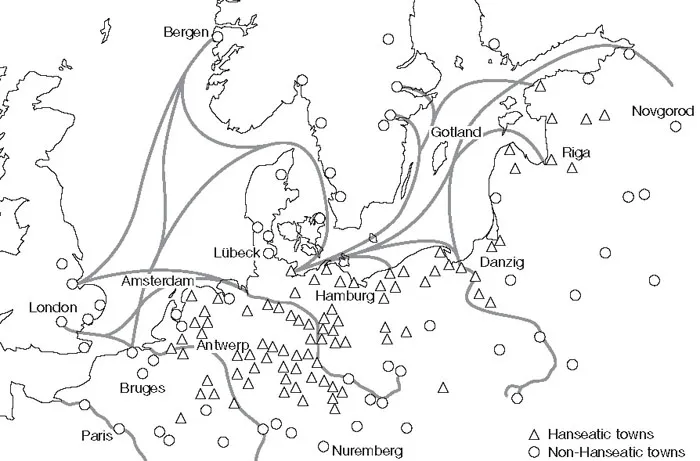

During the fifteenth century two key areas of trade became increasingly important for the whole European economic system. The first coincided with the Italian cities of the Mediterranean including Genoa, Venice, Pisa, Amalfi, Ancona, Naples, Messina and also Sienna and Lucca, which specialized in trade with the East and supplied Europe with indispensable products such as spices.4 They also engaged in trading primary goods such as cereals and raw materials. The second was in the Baltic Sea area, where as far back as the mid-thirteenth century a group of ports, including Bruges and Antwerp, Hamburg, Danzig, Stettin, and Novgorod on the Russian coast, had joined to form part of the Germanic Hanseatic League. Hansa ships sailed from the Baltic Sea to the North Sea through the Sound, and all the northern European countries, including England, depended on them for their supplies.

Map 1 Areas of Hanseatic trade around 1400.

Source: F. Braudel, Civiltà materiale, economia e capitalismo, III, I tempi del mondo, Turin, 1982 [1979], p. 89.

Political factors complicated the pre-existing social and economic balances however. Overland trade was made difficult during the Hundred Years War (1337–1453), but it enabled Bruges to succeed in establishing itself as a midway port. When, at the end of the fifteenth century, Bruges fell out of favour with the Habsburg dynasty, its place was taken by the cosmopolitan mercantile centre of Antwerp, which was also the venue for one of the first international commodity exchange markets.

Goods, routes and means of transport

Throughout the fifteenth century, and for much of the sixteenth, the most important economic sector in Europe continued to be the production and trading of textiles. Tens of thousands of lengths of wool and silk cloth were traded and redistributed from Flanders, the Venetian hinterland, Tuscany and the important Italian ‘silk cities’ such as Lucca, Venice, Florence and Genoa. There was also a significant seaborne trade, involving bulk commodities such as grain, salt and timber. Important raw materials like iron, lead, tin, copper, leather, wax and furs, as well as grains such as rye, oats and barley, were transported to the North Sea ports by the Hanseatic League, while cargoes of Asian and Mediterranean produce such as oil, wine, spices, rice, dried figs, raw wool, dyes, alum5 and textiles arrived from the opposite direction. Goods with a high unit value and low bulk were exchanged at international trade fairs such as the one in Champagne, which had been taking place since the thirteenth century, or in Geneva and Lyons since the fourteenth century. Every three months these fairs provided important meeting places for merchants, who came from the main countries, both north and south, to exchange goods and conduct their business transactions.6

Transporting goods along the various trade routes was not always easy. Mule caravans loaded with goods and people had to cross the Alps over passes that were often deep in snow. In the interior of Europe there were plenty of regular services and shipments along the rivers and canals, but there were still numerous obstacles, such as water mills or fulling works in mid-stream, that made costly transfers necessary. There were also dues and tolls to pay, or services that were under the monopoly of the corporations. The route of choice was therefore the sea; the transport it provided was slow and hazardous, owing to mishaps caused by human error or acts of nature, but it was undoubtedly less costly. Sailings did not usually take place in winter, but this was offset by the greater distances that could be covered and the high profits from the transport of both expensive goods and the relatively cheap bulk commodities. Before the explorations and geographical discoveries at the end of the fifteenth century, ships still sailed within sight of the coast wherever possible, but there was a gradual increase in the tonnage of the vessels. These were now being equipped with a greater number of masts and with stern rudders, and were making better and more rational use of sail power. Alongside the rowing galleys,7 ships known as carracks, or navis, were appearing, and caravels later in the fifteenth century. For coastal navigation smaller boats were used. They were similar one to another but often had very different names. Throughout the century improvements to instruments, and developments in cartography, gradually reduced the margins of error and lowered the risks that were an integral part of navigation.

The gradual development of an efficient money market

In medieval tradition, going back to the time of Charlemagne, the treasury held the right to mint coins. It was a right that the most important cities also claimed for themselves, and when after lengthy and often difficult negotiations they succeeded in winning that right, they guarded it closely. Monarchs resisted this, since coins were seen as a symbol of sovereignty, but also, and perhaps more important, because the mint was a primary source of financial revenue. The revenue was acquired either legally through the right of ‘seigniorage’8 or illegally through gains the treasury could make by issuing coins of increasingly poor quality but whose legal value remained unchanged.

During the early Middle Ages the only coin actually in circulation was the silver denaro, whose weight and fineness varied considerably from one mint to another and from one year to the next. However, the general tendency was for these to decrease, one reason being the scarce supply of the metal on the markets. With rare exceptions, gold, as a means of payment, was used in the form of objects or bars whose value was measured by weight, or in the form of Byzantine or Arab coins. The wide availability of these coins delayed monetization in the western areas of Europe even after 1000, which was a period of strong recovery in trade that coincided with the first Crusades, a considerable increase in population and a steady decline in barter.

In the period until the eleventh century, exchanges were typically made using forms of payment that the French historian Frédéric Mauro has defined as ‘borderline’. For example a family made use of any surplus goods, produced beyond its own needs, for the purpose, though this arrangement was more common in country areas and generally in closed economies. Barter was widely practised on regional or international markets, and for this purpose salt was one of the most enduring commodities. Another widespread form of ‘payment’ was the free provision of care and medical treatment for much of the population, by the Church and the monastic orders. Before the spread of printing, parishes and convents provided education and culture. They also organized water supplies in the urban centres.

After the mid-thirteenth century, coin gradually made its way into every field of economic life; even feudal taxes that had been payable in kind were now starting to be paid in money. Some historians maintain that the first gold coin of any importance was the genovino, which was coined in Genoa and dated back to the second half of the twelfth century. The fiorino, issued in Florence, and the Venetian gold ducat, later called the zecchino, belonged to a slightly later period. France followed the example set by the Italian cities and in 1266 issued the parigino, while some years later England did the same with the noble. However, the development of a money market was delayed because there was insufficient precious metal in circulation suitable for coining. Thus, until the mid-fifteenth century, there was a considerable discrepancy between supply and demand. Only modest quantities of precious metals were being extracted and, in any case, these were only partly used for coinage. Gold, as well as silver, was required for making jewellery and plate, church and convent treasures, which were considered as risk-free investments.

In the second half of the century the bimetallic system developed in Europe, and the search for new deposits of gold and silver produced positive results; meanwhile the increasing price of metal provided a further impetus. The application of new mining techniques that were being developed led to better exploitation of the known deposits. The availability of silver increased with the improved exploitation of German, Austrian and Hungarian mines, and at the end of the century there were increases in the quantities of gold. Two simultaneous circumstances caused an increase in the availability of gold. First there was the exploitation of the gold reserves in Guinea and Senegal, following the Portuguese explorations along the African coasts. These sources boosted the circulation of European money, supplementing the gold supplies that had long been coming from the Sudan, across the Sahara to North Africa, where they were exchanged for Italian and Spanish products. Second there was the result of the early voyages of Columbus that brought the ‘gold of the isles’ from Santo Domingo, Porto Rico, Cuba and the Antilles into Spain.

However, even this was still very little compared with the growing needs of the economic system of Europe, the development of which was closely linked with variations in the available quantities of precious metals and the instability of their value. Here it should be pointed out that the monetary organization of all states was based on a distinction between real, or coined, money and money of account, between which the state fixed a ratio. Money of account acted as a unit of measure for the currency in circulation,9 and, at least until the sixteenth century, was rock-solid.

All in all there were many different coins circulating in Europe, yet, at the same time, attempts were being made to bring stability to the international money market. Apart from money of account, there was also a tendency towards trying to keep the exchange ratios constant. Two examples illustrate the efforts that were made to bring order and innovation to a technically archaic system. First there was the formation of the Rhenish Monetary Confederation in the fifteenth century; eleven sovereigns and seventy-four German cities signed an agreement whereby, for a certain period, the Rhenish florin was to act as the only legal currency. Second there was the scudo di marco, which had a more sophisticated and significant purpose; this type of money of account had first circulated in the thirteenth century fairs of Champagne, and during the course of almost three centuries had gradually merged in such as way as to meet the needs of merchants from different countries.

It is more difficult to assess how rapidly money circulated in the fifteenth century. Gold was circulating less rapidly than silver (through the effects of Gresham’s law10); this circumstance was further conditioned by individual territorial circumstances, the role of credit, and the slow recovery of capital invested in commerce and manufacturing. The consequences were to be much greater in the following century, when the first great period of European inflation occurred, and when there was exceptional development in commercial and financial business on an international level. From this point of view the fifteenth century, pa...