- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Hong Kong is a small city with a big reputation. As mainland China has become an 'economic powerhouse' Hong Kong has taken a route of development of its own, flourishing as an entrepot and a centre of commerce and finance for Chinese business, then as an industrial city and subsequently a regional and international financial centre.

This volume examines the developmental history of Hong Kong, focusing on its rise to the status of a Chinese global city in the world economy. Chiu and Lui's analysis is distinct in its perspective of the development as an integrated process involving economic, political and social dimensions, and as such this insightful and original book will be a core text on Hong Kong society for students.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hong Kong by Stephen Chiu,Tai-Lok Lui in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Japanese History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Global connections

Centre of Chinese capitalism

Hong Kong, as a place, was and continues to be at the organizing center of Chineseled capitalism. Hong Kong assumed this role shortly after its founding in the nineteenth century and continued it until World War II. Then after the war and the Chinese revolution, Hong Kong was the first location where Chinese capitalism reemerged, although in a somewhat changed form.

(Hamilton 1999:15)

Introduction

Exposure to globalization is hardly new to Hong Kong. Right from its beginnings as a British colony in the nineteenth century, Hong Kong was declared a free port (by Elliot in June 1841) with no restrictions on foreign trade and investment. It subsequently became an important trading port as well as a commercial city not only for advancing the economic and political interests of the British Empire but also for facilitating regional trade and finance between China and other Asian economies. Indeed, Hong Kong’s strength as a commercial city and trading port lies in her interconnectedness with not one but a variety of economic networks. This chapter provides a historical backdrop to our discussion of the emergence of Hong Kong as a centre of Chinese capitalism for the past 160 years.

The beginning

Archaeological findings suggest that human settlements in Hong Kong date back to 6000 BC. The discovery of an Eastern Han (AD 25–220) tomb in Kowloon is another piece of archaeological evidence of a long historical connection with the southern region of the mainland. But regular Chinese settlement in the New Territories began only during the Song dynasty (Hayes 1977:25). During the Tang dynasty, garrisons were established in Tuen Mun, where the Portuguese landed in 1514. According to the official gazetteer records that first appeared in the late sixteenth century, what was later to become Hong Kong, Kowloon and the New Territories were included in San On County. In brief, the history of Hong Kong does not begin with the arrival of the British. But, once it became a colony, Hong Kong was channelled towards a different path of development.

Hong Kong was first occupied by British troops in 1841 and then formally ceded to Britain under the Nanjing Treaty in 1842. Hong Kong island was, by British accounts, sparsely populated at that time. A statement on the conditions of the Island of Hong Kong prepared in 1844 reported that:

On taking possession of Hong Kong, it was found to contain about 7,500 inhabitants, scattered over 20 fishing hamlets and villages. The requirements of the fleet and troops, the demands for labourers to make roads and houses, and the servants of Europeans, increased the number of inhabitants, and in March 1842, they were numbered at 12,361. In April, 1844, the number of Chinese on the island is computed at 19,000, of whom not more than 1,000 are women and children. In the census are included 97 women slaves, and the females attendant on 31 brothels, eight gambling-houses, and 20 opium shops, &c. … There is no trade of any noticeable extent in Hong Kong.

(Jarman 1996:9, 11)

R. Montgomery Martin, the Colonial Treasurer who prepared this statement on Hong Kong, objected to the choice of the island for British occupation, arguing that, ‘On a review of the whole case, there are no assignable grounds for the political or military occupancy of Hong Kong, even if there were no expense attending that occupancy’ (Jarman 1996:16). This echoed the comment by Lord Palmerston, the British Foreign Secretary, to Elliot concerning his occupation of Hong Kong that it was, in his eyes, ‘a barren island with hardly a house upon it’ (quoted from Welsh 1997:108). Palmerston further remarked that ‘it seems obvious that Hong Kong will not be a Mart of Trade’ (Welsh 1997:108). The acquisition of Hong Kong was not without controversy among the British (Carroll 2005:38–46) and this controversy continued for years afterwards (Zhang 2001:21–2). Chusan, which was strategically located for future interests in Guangzhou, was repeatedly cited as a better choice for the advancement of British interests. In fact, as shown in Martin’s exchanges with the British government, even after the exchange of the ratifications of the Treaty of Nanjing, arguments about the desirability of the acquisition of Hong Kong continued. Our point here is that while British descriptions about the barrenness of Hong Kong might have been overstated, they did point to an important fact about the motivation for the colonization of Hong Kong: the British had their eyes on expanding business opportunities with China, and Hong Kong was not an obvious choice of acquisition for that purpose.

The British had in fact seriously entertained the idea of surrendering Hong Kong in exchange for other, more economically promising concessions from China. But Pottinger, who was initially hugely disappointed by the Chuenpi agreement, was later convinced of ‘the necessity and desirability of our possessing such a settlement as an emporium for our trade and a place from which Her Majesty’s subjects in China may be alike protected and controlled’ (quoted in Endacott 1973:22). To conduct business with China, the British needed a sheltered harbour and a land base for related logistics. These, and not Hong Kong’s natural resources nor a population constituting an attractive market, were the primary advantages of Hong Kong

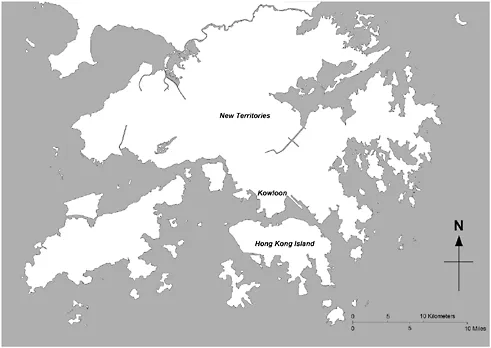

for the British. Because of these considerations, the British did not develop their base in existing major settlements in the Eastern and southern parts of the island but set up their military and administrative operations on the northern shore instead (Ho 2004:17). This area was developed into the City of Victoria. Later, with the cessation of Kowloon in 1860 and the lease of the New Territories in 1898, the territorial boundaries of colonial Hong Kong were finalized (see Figure 1.1). Despite her long historical linkages with China, Hong Kong’s subsequent development into a trading port and commercial city, boosted by an influx of Chinese, was largely an outcome of the rise of the City of Victoria.

Figure 1.1 Map of Hong Kong

The rise of a city of trade, commerce and finance

As one might have guessed from the above discussion about the controversy among the British over the acquisition of Hong Kong, there were few signs during the early years of colonization foretelling Hong Kong’s subsequent economic success. Contrary to Pottinger’s prediction in 1842 that ‘Within six months of Hong Kong being declared to have become a permanent Colony, it will be a vast emporium of commerce and wealth’ (quoted in Endacott 1973:72), the City of Victoria soon found itself in a difficult situation. The opening of five treaty ports to the British, as stipulated in the Treaty of Nanjing, actually undermined Hong Kong’s role as a centre of transhipment. Indeed, in the 1840s, ‘Hong Kong survived …, not primarily through the development of a free trade between Britain and China (which took place slowly at the mainland ports), but as a depot for two semi-monopolistic and still technically illegal enterprises: the importation of opium into China and the traffic in labourers out of China’ (Munn 2001:23). Hong Kong thus did not develop into an important port for entrepot trade immediately after the arrival of the British.

It did not take long, however, before the City of Victoria was turned from a British frontier colony into a vibrant trading and commercial city. Following closely behind the military troops, major British traders almost immediately moved their head offices for their business operations in the region to Hong Kong (Endacott 1973:76; Tsang 2004:56–7). In this connection, Hong Kong was also gradually developed into a centre for services, more precisely shipping and repair services, for the businesses concerned.

It was during the 1850s, however, that Hong Kong’s prospects ‘were becoming brighter’ (Fairbank 1969:239) as the island experienced a rapid growth of economic activity. The Chinese population in Hong Kong increased sharply during this period, rising from 28,297 in 1849 to 85,280 in 1859 (Tsai 1993:22, 299). Two external factors facilitated this turnaround in Hong Kong’s business fortunes. First, the discovery of gold and the resultant gold rush in California in 1848 and then a couple of years later in New South Wales, Australia, created a strong demand for labourers. Hong Kong became, as a result of increasing activity related to the dispatch of Chinese coolie emigrants abroad, ‘the key staging post for Chinese emigration’ (Tsang 2004:58). Second, political and social disorder on the mainland drove people from the southern part of China, both merchants and labourers, to seek refuge in Hong Kong (Fan 1974:1). This experience was to be repeated a number of times in the course of Hong Kong’s history: ‘trouble in China was a “god-send” for Hong Kong’ (Munn 2001:49; also see Eitel 1983:259). As Carroll (2005:50) notes, ‘The combination of the Taiping Rebellion and the growth of Chinese communities overseas did more than save Hong Kong from an economic depression; it changed the island’s basic reason for being. Hong Kong was transformed from a colonial outpost into the center of a transnational trade network stretching from the China coast to Southeast Asia and then to Australia and North America.’ And Hong Kong was quick to capitalize on these new opportunities, changing itself in the process into a seaport with growing business activity.

The business of exporting Chinese labourers began in Xiamen in 1845 (Peng 1981:181). The huge demand for Chinese labourers sprang from the gold rush in the United States of America and Australia, and the intensification of colonization and capitalist penetration into Asia and Latin America. Chinese labourers, who were cheap and productive, were much in demand and were exported not only to the USA and British colonies, but also to more remote places such as Cuba and Peru (Peng 1981:191). The emigration business enabled the shipping companies, brokers and labour recruiters to make huge profits from the coolie trade. But the impacts of the emigration business extended far beyond benefiting those directly involved in the organization of coolie labour. Closely related to the emigration business were rope manufacturing, shipbuilding, repairing and refitting, and provisioning for ships. As a result of the growth of coastal and international shipping services, the demand for professional services increased so that medical facilities, legal advice, money exchange and insurance services became available. The growth of overseas Chinese communities (and their demands for supplies from their native places) stimulated an increase in international commercial and trading activities. Indeed, ‘both European and Chinese mercantile communities in Hong Kong prospered by providing commercial, financial and professional services’ (Tsai 1993:26). More critically, the demand for financial services, particularly services driven by the emigrant labourers’ remittances to their hometowns (Hamashita 1997a), created the conditions for the growth of banking and financial activities in Hong Kong from the 1860s.

As noted above, the emigration business involved more than simply human trafficking. The rise of Chinese communities abroad created demands for commercial and financial activities. The establishment of the so-called ‘jinshan zhuang’ and ‘nanyang zhuang’ in Hong Kong, firms specialized in shipping supplies to North America and Australia, and Southeast Asia respectively, served as intermediaries between the growing overseas Chinese communities and the emigrants’ home-towns (Zhang 2001:182–7). In addition to the shipment of supplies to overseas Chinese communities, these ‘jinshan zhuang’ and ‘nanyang zhuang’ also assumed the role of recruitment agents for emigrant labourers and financial intermediaries. They handled in particular the remittances of emigrant labourers. And that business gradually evolved into commercial lending and credit as well.

In brief, Hong Kong’s participation in the transhipment of emigrant labourers and goods had a much bigger impact on its economy and society than merely promoting shipping and related activities. A whole cluster of economic activities, from shipping and related manufacturing activities to commerce and finance, grew concomitantly with the rise of Hong Kong as a seaport. Internal trade within China also reinforced the momentum of economic growth and development in Hong Kong. As Kose (1994) argues, major centres of commerce and finance like Hong Kong and Shanghai benefited enormously from Chinese internal trade. First, they were centres of regional economies. Second, internal trade was controlled primarily by Chinese merchants. Because of a shortage of currency, most of the trading activities and the related financing (e.g. the issuing of certificates of credit) were carried out by a settlement system under the Chinese merchants’ control. This settlement system worked as a clearing house for business transactions among the local merchants. As a result, Hong Kong and Shanghai functioned both as a centre of trade and of settlement. And because of their international connections, Hong Kong and Shanghai had an additional advantage:

The settlement system was profitable for the Chinese import–export merchants and promoted bartering. It made trade expansion possible even when little silver cash was available. … Foreign merchants did not have locally produced Chinese goods which could be exchanged together with their goods. … This placed foreign merchants at a disadvantage, and in the late nineteenth century foreign merchants withdrew from local ports to trading centres at Shanghai or Hong Kong.

(Kose 1994:140–1)

There are two points to note here. First, once Hong Kong’s pace of development picked up from the 1850s, the different kinds of economic activity worked to reinforce each other in strengthening Hong Kong’s role as a commercial and financial intermediary in the changing global economy (Endacott 1964a: xiii, xv). Hong Kong became a base of operations for British traders’ head offices, a centre for the transhipment of emigrant labourers, a seaport with growing supporting industries for interregional and international trades, and a financial hub for remittances and the settlement of payment for commercial activities. Not only did each of these activities develop its forward and backward linkages, thus reinforcing the momentum of growth and development, more importantly together they brought Hong Kong into world and regional trading, financial and migration networks. They literally put Hong Kong on the map of the world economy.

Second, Hong Kong’s rise as a centre of trade and finance was not simply an outcome of Western colonialism (also see Carroll 2005). Nor can we explain Hong Kong’s changing path of development in the nineteenth century simply from the perspective of the metropolitan centre of imperialism (cf. Stoler and Cooper 1997:29). The socio-economic development of Hong Kong was not determined by the metropolitan centre. Pre-existing interregional and transnational networks of economic activity were equally, if not more, important in shaping Hong Kong’s path of development:

The growth of Hong Kong after 1842 into an entrepot owed a great deal to the interregional and international trades already developed in the region centuries before the Opium War. In fact, British Hong Kong inherited these trades, which had long been carried on, with Canton and Whampoa as a transhipment port for commodities from various parts of China, Northeast Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Western world.

(Tsai 1993:17)

And Hong Kong was not alone in finding that the immediate impacts of colonialism were more limited than expected. Singapore, another British colony and an important trading port in Southeast Asia, was also a case that experienced little direct benefit from British imperial connections. In fact, Britain was ‘not a very important trading partner’ (Latham 1994:158–9) for both Singapore and Hong Kong. Singapore’s rise to the status of important trading port had a lot to do with its intra-Asian trading networks:

[T]he dynamic element in Singapore’s trade was Western purchases of tin and rubber, which drew imports to Singapore which were then re-exported West. The purchasing power which was thus transmitted to Singapore and Asia was not then channelled back to Britain, America and other Western countries, but retained in Asia where it was spent to a considerable extent on rice and other foodstuffs, and the manufacturers of Asia’s emergent industries.

(Latham 1994:151)

In sum, the significance of Singapore and Hong Kong, both being British colonies, lay not in distributing British exports within the region, but in assuming the role of reallocation and distribution of Asian goods within Asia. ‘They were the twin hubs of intra-Asian trading activity, not merely British trading outposts’ (Latham 1994:145).

The pre-existing intra-Asian trading networks played a crucial role in facilitating Hong Kong’s economic development after 1841. The formation of these trading networks can be traced back to the tributary system in Asia, which ‘consisted of a network of bilateral relationships between China and each tribute-paying country, with tribute and imperial “gift” as the mediums of exchange and the Chinese Capital as the center’ (Hamashita 1997b: 120; also see Hamashita 2003). More importantly, the tributary system grew in parallel with or ‘was in symbiosis with a network of commercial trade relations’ within the region (Hamashita 1997b: 120). Hong Kong’s success in locking in to these pre-existing commercial networks, and not its trade and finance with the metropolitan centre of the imperial power, marked the first major turning point in its economic development. Hong Kong captured such opportunities through inheriting the historical trading centre of Canton, and developing into a centre of trade and finance for the intra-Asian economic networks and the international market. It transformed itself in the process from a colonial outpost that served other economic purposes into a city of trade, commerce and finance.

Consolidation of a regional and international business centre

In an article entitled ‘A glance at Hongkong in 1850’, Dr J. Berncastle, a physician passing through the colony on his way to England from Canton, described Hong Kong as ‘a dull place for a stranger to remain in more than a few days’ (quoted in Bard 1993:42–3). In Berncastle’s description, the main street, Queen’s Road, ‘extends the whole length of the town. In it are the principal offices of the merchants, banks, and shops … filled with all sorts of European goods’ (Bard 1993:41). And piracy was a problem. ‘There is seldom a week without some attack taking place upon fishing boats or passage-boats, in these waters’ (Bard 1993:41). The description by the famous Russian playwright Anton Chekhov, who visited the colony in October 1890, was very different: ‘[Hong Kong] has a glorious bay, the movement of ships on the ocean is beyond anything I have seen even in pictures, excellent roads, trolleys, a railway to the mountains, museums, botanical gardens; wherever you turn you will note evidences of the most tender solicitude on the part of the English for men in their service; there is even a sailors’ club’ (Bard 1993:50).

Between 1850 and 1890, Hong Kong consolidated its position as an entrepot within the region. Indeed, once Hong Kong entered into the regional and international networks of trade, commerce and finance, it was able to capitalize quickly on the opening of new opportunities. Despite growing competition from other treaty p...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Global connections: centre of Chinese capitalism

- 2 An industrial colony: Hong Kong manufacturing from boom to bust

- 3 The building of an international financial centre

- 4 A divided city?

- 5 Decolonization, political restructuring and post-colonial governance crisis

- 6 The return of the regional and the national

- 7 A Chinese global city?

- Notes

- Bibliography