eBook - ePub

Recovery and Wellness

Models of Hope and Empowerment for People with Mental Illness

- 180 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Learn to harness the process of recovery from mental illness for use in the transformative healing of your OT clients!This informative book for occupational therapists describes the Recovery Model from theoretical and experiential perspectives, and shows how to use it most effectively. It examines the major constructs of the model, describes the recovery process, offers specific OT approaches to support recovery, and provides guidelines for incorporating wellness and recovery principles into mental health services.This unique book you will show you:

- how recovery--in this case from schizophrenia--can be used as a transformative healing process

- the challenges and benefits of a dual role as a mental health professional and a consumer of mental health services

- the story of one occupational therapist's journey of discovery in relation to her own mental illness

- why treating mental illness as a medical problem can be counterproductive to recovery

- three different teaching approaches--the executive approach, the therapist approach, and the liberationist approach--and how they lead to dramatically different outcomes

- the vital relationship between occupational therapy and recovery and wellness--with an enlightening case study

- how to use the Adult Sensory Profile to evaluate and design interventions for sensory processing preferences

- a system for monitoring, reducing, and eliminating uncomfortable or dangerous physical symptoms and feelings

- how to establish partnerships between mental health researchers and persons with psychiatric disabilities

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One: Consumer/Survivor Perspectives

Recovery as a Self-Directed Process of Healing and Transformation

Patricia E. Deegan, PhD

SUMMARY. This paper describes a first person account of recovering from schizophrenia. Recovery is described as a transformative process as opposed to merely achieving stabilization or returning to baseline. The self-directed nature of the recovery process is highlighted with suggestions as to how professionals can support recovery. [Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <[email protected]> Website: <http://www.HaworthPress.com> © 2001 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.]

KEYWORDS. Recovery, schizophrenia, self-help, coping, hope

Recovery is often defined conservatively as returning to a stable baseline or former level of functioning. However, many people, including myself, have experienced recovery as a transformative process in which the old self is gradually let go of and a new sense of self emerges. In this paper I will share my personal experience of recovery as a self-directed process of healing and transformation and offer some suggestions as to how professionals can support the recovery process.

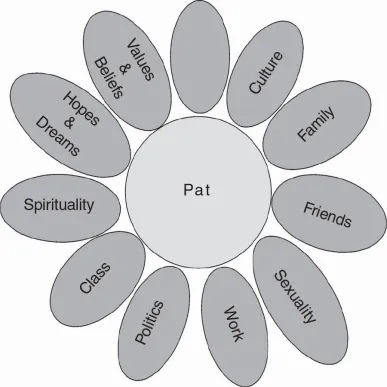

When I was seventeen years old and a senior in high school, I began to have experiences of severe emotional distress that eventually were labeled as mental illness. Illustration 1 symbolizes how I experienced myself and how others perceived me before I was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Illustration 1. How I Was Seen by Others and Understood Myself Before Being Diagnosed with Mental Illness

The most immediate impression of this symbolic flower is its integrity and wholeness. This represents the fact that before being diagnosed with mental illness there was a basic congruity between how I understood myself and how others perceived me. In addition, each of the petals on the flower represent aspects of who I was. I was the oldest child in a large working-class Irish Catholic family. My friends, my social role as a worker and student, my spirituality, values and beliefs, culture, family and socio-economic class all converged to form the unique individual I was at seventeen years old.

Notice that one of the petals on the flower is empty. This empty petal symbolizes the idea that my life opened onto a future. That future was unknown and ambiguous. It was precisely because my future was unknown that I could project my hopes, dreams and aspirations into it. That is, hope arises in relation to an open, ambiguous and uncertain future. As a teenager, I remember my dream was to become a coach for women’s athletic teams. I was a gifted athlete and did just enough academic work to get passing grades so I could continue to compete on varsity teams. At seventeen I could not have imagined that someday I would have a doctorate in clinical psychology and be writing a chapter for a book!

The image of me as a whole, unique and promising young person began to crumble during the winter of my seventeenth year. Even now I can vividly recall some aspects of the emotional distress I began to experience. For instance, during basketball practice it became harder and harder to catch a ball. My depth perception and coordination seemed strangely impaired and I found myself being hit in the head with passes rather than catching the ball. Objects around me also began to look very different. Countertops, chairs and tables had a threatening, ominous physiognomy. Everything was thrown into a sharp, angular and frightening geometry. The sense that things had utilitarian value escaped me. For instance, a table was no longer something to rest objects upon. Instead a table became a series of right angles pointing at me in a threatening way.

A similar shift in my perception and understanding occurred when people spoke to me. Language became hard to understand. Gradually I could not understand what people were saying at all. Instead of focusing on words, I focused on the mechanical ways that mouths moved and the way that screwdrivers had taken the place of proper teeth. It became difficult to believe that people were really who they said they were. What I remember most was the extraordinary fear that kept me awake for days and the terrible conviction I was being killed and needed to defend myself.

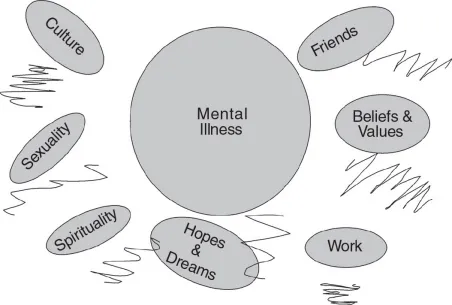

The adults around me eventually decided that I had “gone crazy,” and I soon found myself being escorted up a hospital elevator by two men in white uniforms. Once in the mental hospital, I was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Illustration 2 represents the way I was viewed by those around me once I had been diagnosed:

Illustration 2. How I Was Seen by Others After Being Diagnosed with Mental Illness

Whereas before being diagnosed I was seen as a whole person, after being diagnosed it was as if professionals put on a pair of distorted glasses through which they viewed me as fundamentally ill and broken. The jagged lines represent the distorted lens through which I was viewed. It seemed that everything I did was interpreted through the lens of psychopathology. For instance, when growing up, my grandmother used to say I had ants-in-my-pants. Now, in a mental hospital, I was agitated. I never cried very much while growing up, but after diagnosis I was told I had flat affect. I was always quiet, shy, and introverted. Now I was guarded, suspicious and had autistic features. And in a classic double-bind, if I protested these pathologized interpretations of myself then that was further proof I was schizophrenic because I lacked insight!

Notice also that in the first illustration there was congruity between how I viewed myself and how others viewed me but after being diagnosed there was a lack of congruity. That is, although I was severely distressed, I still felt that deep down I was myself–Pat. However, the professionals, and later my family and friends, seemed to forget about Pat and were now more interested in “the schizophrenic.” This is symbolized by the substitution of a diagnosis for my name in the center circle.

After being diagnosed, mental illness took on a master status in terms of how others viewed me. The fact that I was a unique person with my own spirituality, culture, sexuality, work history, and values and beliefs was secondary–one might even say perfunctory. This is symbolized by the petals being broken off, and even missing altogether. What mattered most to psychiatrists, social workers, nurses, psychologists and occupational therapists was that I was a schizophrenic. My identity had been reduced to an illness in the eyes of those who worked with me. It was only a matter of time before I began to internalize this stigmatized and dehumanized view of myself.

Dehumanization is an act of violence, and treating people as if they were illnesses is dehumanizing. Everyone loses when this happens. People, especially people who are feeling very vulnerable, internalize what professionals tell them. People learn to say what professionals say; “I am a schizophrenic, a bi-polar, a borderline, etc.” Yet instead of weeping at such a capitulation of personhood, most professionals applaud these rote utterances as “insight.” Of course the great danger of reducing a person to an illness is that there is no one left to do the work of recovery. If all professionals see are schizophrenics, borderlines, bi-polars, etc., then the resilient strengths and gifts of the individual are ignored and sacrificed to the gods of the DSM-IV.

Notice that the empty petal is missing from Illustration 2. This symbolizes the fact that because of my diagnosis professionals lost hope that I could have a meaningful future. Recall how in the Illustration 1 the empty petal symbolized the unknown, ambiguous future into which I projected my hopes, dreams and aspirations. Once diagnosed with schizophrenia, professionals acted as if my future and my fate were sealed. I recall the day this happened to me: I asked my psychiatrist what my diagnosis was. He looked at me from behind his desk and said, “Miss Deegan, you have a disease called schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is a disease like diabetes. Just like diabetics have to take medications for the rest of their lives, you will have to take medications for the rest of your life. If you go into this halfway house, I think you will be able to cope.”

“You are Wrong”

Coping is definitely not what a teenager wants to do on a Friday night! I was not at all inspired by the thought of a life spent coping. I remember feeling like I had been hit by a truck upon hearing his words. Then I remember my mind racing, trying to think of one famous person who was diagnosed with schizophrenia. I instinctively needed to identify someone who had beat the odds but nobody came to mind. As the psychiatrist continued to babble on, I felt a surge of anger rising up within me. Although I knew better than to get too angry in a psychiatrist’s office, I found the words forming silently inside me: “You are wrong. I’m not a schizophrenic. You are wrong!”

Today I understand that this psychiatrist did not give me a diagnosis. He gave me a prognosis of doom. Essentially this psychiatrist was telling me that by virtue of the diagnosis of schizophrenia, my future was fait accompli. He was telling me that the best I could hope for was to cope and remain on medications for the rest of my life. He was saying my life did not open upon a future that was ambiguous and unknown. He was saying my future was sealed and the book of my life had already been written nearly 100 years earlier by Emil Kraepelin (1912), the psychiatrist who wrote a pessimistic account of schizophrenia that influences psychiatrists even to this day. According to Kraepelin, my life, like the life of all schizophrenics, would be a chronic deteriorating course ending in dementia (Kruger 2000).

It was this prognosis of doom, this life sentence, this death before death that I instinctively rejected when the words “You are wrong” formed silently within me. With the wisdom of hindsight I understand why this moment in the psychiatrist’s office was a major turning point in my recovery process. When I rejected the prognosis of doom I simultaneously affirmed my worth and dignity. Through my angry indignation I was affirming that “I am more than that, more than a schizophrenic.” Importantly, it was my anger that announced the resurrection of my dignity after it had been so battered down during hospitalizations. My angry indignation was a sign I was alive and well and resilient and intent on fighting for a life that had meaning and hope. What some would have seen as denial and a lack of insight into my illness, I experienced as a turning point in my recovery process.

My Dream

Rejecting the hopeless prognosis through angry indignation happened almost like a reflex. And just as quickly as I turned away from the prophecy of doom, I found myself asking–so now what? In other words, I turned away from a hopeless path but also, at the same time, had to turn toward something. What I remember was that when I left the psychiatrist’s office, I stood in the hallway and had an image in my mind’s eye of a big heavy key chain–the type carried by the most important and powerful professionals who have the keys to all the hospital doors. I found myself thinking, “I’ll become Dr. Deegan and I’ll make the mental health system work the right way so no one else ever gets hurt in it again.” And this plan became what I have come to call my survivor’s mission. Yes, it was a grand dream that would have to be molded and modified with time and maturity. But it was my dream nonetheless and it became the project around which I organized my recovery.

I did not tell anyone about my dream. In hindsight this was very wise. Imagine if I had gone to my treatment team as an 18-year-old girl diagnosed with chronic schizophrenia, having had three hospitalizations, barely graduating from high school with combined SAT scores of under 800–and announcing that my plan was to become Dr. Deegan and transform the mental health system so it helped instead of hurt people. Delusions of grandeur! Clearly it was better to keep my dream to myself.

The Coke and Smoke Syndrome

I wish I could say that having found a survivor’s mission I resolutely marched forward in my recovery. But recovery does not strike like a bolt of lightening wherein one is suddenly and miraculously cured. The truth is, when I returned home after that transformative experience, I proceeded to sit and chain smoke in the same chair I had been sitting and smoking in for months. In other words, although everything had changed within me, nothing had changed on the outside yet. Here is what people would have seen me doing at that time in my life:

I turn my gaze back over the years. I can see her yellow, nicotine-stained fingers. I can see her shuffled, stiff, drugged walk. Her eyes do not dance. The dancer has collapsed and her eyes are dark and they stare endlessly into nowhere . . . She forces herself out of bed at 8 o’clock in the morning. In a drugged haze she sits in a chair, the same chair every day. She is smoking cigarettes. Cigarette after cigarette. Cigarettes mark the passing of time. Cigarettes are proof that time is passing and that fact, at least, is a relief. From 9 a.m. to noon she sits and smokes and stares. Then she has lunch. At 1 p.m. she goes back to bed to sleep until 3 p.m. At that time she returns to the chair and sits and smokes and stares. Then she has dinner. She returns to the chair at 6 p.m. Finally, it is 8 o’clock in the evening, the long-awaited hour, the time to go back to bed and to collapse into a drugged and dreamless sleep.

The same scenario unfolds the next day, and then the next, and then the next, until the months pass by in numbing succession marked only by the next cigarette and then the next . . . (Deegan 1993, p. 8)

For many months I lived in what I came to call the coke and smoke syndrome. The first truly proactive step I took in my recovery process occurred at the prompting of my grandmother. Each day she would come into the living room as I smoked cigarettes. She would ask me if I would like to go food shopping with her and each day I would say “No.” She asked only once a day and that made it feel like a real invitation rather than nagging. For reasons I cannot account for, one day after months of sitting and smoking, I said “Yes” to her invitation. I now understand that “yes,” and the subsequent trip to the market where I would only push the cart, was the first active step I took in my recovery. Other small steps followed such as making an effort to talk to a friend who had come to visit or going for a short walk.

Recovery Strategies

Eventually it was suggested I take a course in English Composition at the local community college and I agreed. Going to college presented me with a whole new set of challenges such as managing anxiety, distressing voices and suspicions during class time as well as finding ways to concentrate in order to do homework. At the time there were no organized self-help and mutual support groups for ex-patients so I was very much on my own in terms of developing coping strategies. Table 1 lists some of the most important self-care strategies I developed.

Table 1

Some of My Recovery Strategies

- No drugs or alcohol

- Finding tolerant environments

- Relationships

- Spirituality and finding meaning in my suffering

- A sense of purpose and direction; survivor's mission around which to organize my recovery

- Routine

- Day at a time, hour at a time, minutes at a time

- Study, learn, and work

- A willingness to take responsibility for myself and accepting that no one could do the work of recovery for me

- Willingness to do psychotherapy to work through trauma history

- Meeting others in recovery and learning not to be ashamed

- Development of self-care skills:

- How to avoid delusional thinking

- How to cope with voices

- How to cope with anxiety

- How to rest, pace myself, sleep

- Prayer, meditation

- Sensory diet

Through a process of trial and error I discovered self-care strategies that worked for me. For instance, I learned at a young age that street drugs, alcohol and even some over-the-counter drugs such as certain types of cold medications were not good for me. I avoided these and am certain this helped my recovery.

Relationships–especially learning to balance time alone and time with people–have always been an important self-care strategy for me. In the beginning my relationships were quite limited and lopsided in the sense that people tended to care more for me than I did for them. Over time I learned to become more intimate with people and to develop more mutually reciprocal relationships.

Routines were important to me, especially in the early years of my recovery. Sometimes when everything was falling apart inside of me, it was good to be able to rely on routines that would give form and structure to the chaos I was experiencing. Having a sense of purpose, a reason to get up in the morning and a goal to organize my recovery around were important. Studying a wide range of subjects, especially world religions, philosophy and archetypal psychology, were helpful in my efforts to make sense of the experiences I was having. My spirituality and faith tradition had always been a resource for me. Spiritual practices and making an effort to have conscious contact with my God became integral to my recovery. My spirituality offered me a way of finding meaning in my suffering, and that in turn helped me through feelings of anguished futility, self pity and the inevitable “Why me?” questions that come with...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction: Recovery and Wellness: Models of Hope and Empowerment for People with Mental Illness

- Part One: Consumer/Survivor Perspectives

- Part Two: Philosophical Perspectives

- Part Three: Application of Recovery Principles

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Recovery and Wellness by Catana Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.