1

An outline of the English legal system

INTRODUCTION

It is unlikely that the majority of journalists working on magazines will spend much, if any, of their working hours in the courts, but the time spent in acquiring an outline knowledge and understanding of the legal system is essential if they are to avoid ‘howlers’ and understand the legal copy they might be handling.

THE DIVISIONS OF THE LEGAL SYSTEM

There is widespread misunderstanding about the nature of the English legal system. That is why property owners often put up notices warning ‘Trespassers will be prosecuted’, which is a legal nonsense and unenforceable. Most trespasses are a civil law wrong (or tort) and prosecution is a criminal law procedure and the two are not interchangeable.

Historically, the legal system has developed two branches: criminal and civil, each with its own personnel, language and procedures. Although some crimes can also result in actions for damages (for example, a driver convicted of a traffic offence in the criminal courts could also face a claim for compensatory damages by an injured person in the civil courts), each case will be proceeded with independently, with its own rules of procedure.

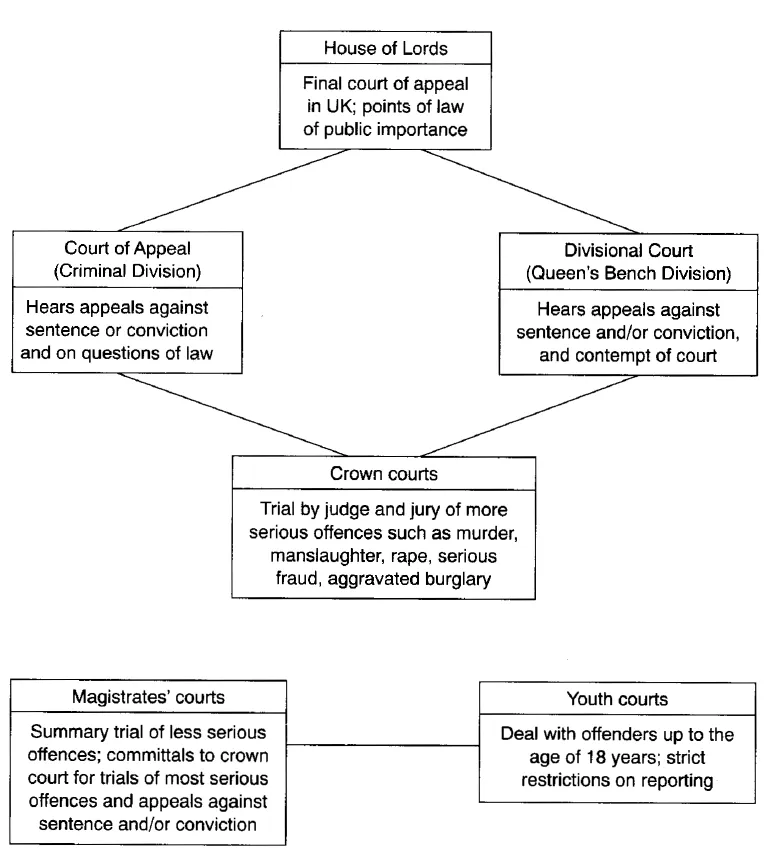

THE CRIMINAL COURTS (see Figure 1.1)

MAGISTRATES’ COURTS

Magistrates are either qualified lawyers and are known as stipendiary (i.e. salaried magistrates), or lay people without necessarily any legal qualifications.

Of all criminal cases, 99 per cent begin in the magistrates’ courts and around 95 per cent of them end there. The odd 1 per cent are started by a Bill of Indictment, a procedure which requires no preliminary investigation. Defendants charged with serious offences, such as murder, manslaughter, rape, robbery and driving offences causing death, have to be committed to the crown court for trial following a preliminary investigation to confirm that there is a case to answer. When this happens there are close restrictions, unless waived by the accused, on what can be reported, limiting stories to the accused’s name, age, occupation and address, and details of the charge(s) against him or her. Reports should not include any evidence heard by the magistrates, only their decisions. Journalists should also remember that until the trial is over all the claims made against the accused are allegations and must be reported as such.

Figure 1.1 An outline of the criminal courts system

The procedure is quite simple. The prosecution, usually the Crown Prosecution Service, will outline the case against the accused to the magistrates and, if the accused pleads guilty, the defence will be allowed to plead mitigating circumstances with the hope of reducing punishment.

If the accused pleads not guilty, the prosecution will outline the facts of the case and call witnesses for the prosecution. These can be cross-examined by the defence. Then it is the turn of the defence to call witnesses on behalf of the accused, and these too can be cross-examined by the prosecution. When all the witnesses have been heard, the magistrates will retire to consider their verdict. They are advised on questions of law, not fact, by the court clerk. If they find the accused not guilty, he or she is free to leave the court. If, however, their verdict is guilty, they will hear evidence in mitigation of sentence from the accused’s lawyer. The prosecution will also give details of any previous convictions. The magistrates will then announce sentence.

If a magistrates’ court decides that its powers of sentence are too limited it will send the accused to the crown court for sentencing.

YOUTH COURTS

These used to be called juvenile courts but in 1991 they were renamed youth courts and are magistrates’ courts that deal with crimes committed by children and young people up to eighteen years of age. They are not open to the public but journalists can attend. Again, there are firm restrictions on what can be reported and any material that is likely to identify the young person involved is not permitted. This includes a ban on publishing their names and addresses, the schools they attend and any photographs.

A youth court consists of justices chosen from a special panel. There must be three lay justices and at least one of them must be a woman.

CROWN COURTS

The crown court system was set up in 1972 to replace assizes and quarter sessions. The Central Criminal Court (or Old Bailey) is a crown court. They try all serious offences such as murder and attempted murder, manslaughter, rape and attempted rape and other sexual offences, major fraud, aggravated burglary and some wounding offences.

Trial is by judge and jury unless the defendant pleads guilty; there is then no need for a jury. The procedure is similar to that in magistrates’ courts although often more formal. The judge rules on questions of law and passes sentence but the jury decides guilt or innocence. Juries are encouraged to reach unanimous verdicts but can arrive at majority verdicts if unanimity has proved impossible. The minimum ratio is 10–2 for a guilty verdict.

The crown court also hears appeals against sentence and/or conviction from magistrates’ courts.

THE HIGH COURT

The criminal jurisdiction of the High Court is carried out in the Queen’s Bench Division and is concerned with appeals from magistrates’ and crown courts and with other matters such as writs for habeas corpus. High Court judges usually preside over the most serious criminal trials, sitting in crown court buildings.

THE COURT OF APPEAL (CRIMINAL DIVISION)

Appeals against sentence and/or conviction can also be heard by the criminal division of the Court of Appeal though these are usually restricted to questions of law rather than of fact. This court also is involved in appeals relating to contempt of court, and is staffed by Lord Justices of Appeal.

THE HOUSE OF LORDS

The highest court of appeal in the United Kingdom is the House of Lords. Hearings are concerned solely with cases involving questions of law of public importance.

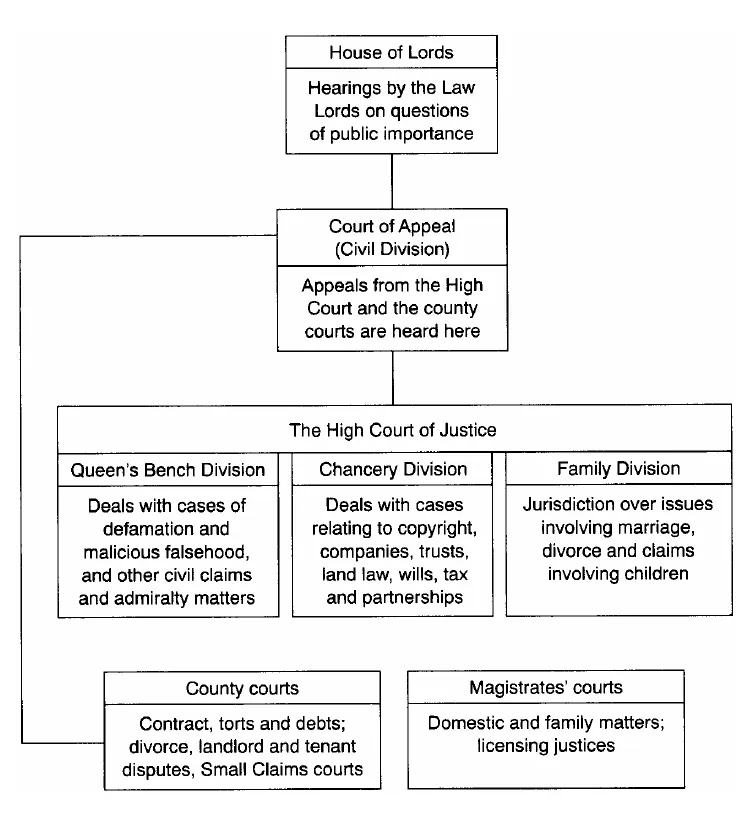

THE CIVIL COURTS (see Figure 1.2)

MAGISTRATES’ COURTS

Although the bulk of the work carried out in the magistrates’ courts involves criminal proceedings they do have a limited amount of civil jurisdiction, particularly relating to family matters, neighbourhood quarrels, keeping the peace and binding over to keep the peace.

Panels of specially appointed magistrates sit as family proceedings courts, dealing with issues of welfare, custody, maintenance and adoption of children and access. They also act as licensing justices.

COUNTY COURTS

County courts have existed since 1846, but their jurisdiction has nothing to do with counties as such. They deal with cases involving contracts and other civil matters where the sum of damages being claimed is less than £50,000. Their jurisdiction is being constantly enlarged. In 1995 certain patent cases were referred to county courts. The Small Claims courts are part of the county courts and deal with claims for under £3,000. Their purpose is speed and informality. Generally the parties have to meet their own costs, including those of their solicitors.

Figure 1.2 An outline of the civil courts system

THE HIGH COURT

The High Court has three divisions and unlimited jurisdiction, and is staffed by High Court judges. Chancery Division judges hear cases relating to copyright, companies, trusts, land law, wills, tax and partnerships. The Family Division has jurisdiction over issues involving marriage, divorce and claims involving children, and admiralty matters, hence the old slogan: Wives, Wills and Wrecks.

Journalists who are involved in actions for defamation or for malicious falsehood will find themselves appearing in the Queen’s Bench Division, where most serious civil claims are heard.

THE COURT OF APPEAL (CIVIL DIVISION)

Appeals from the High Court and the county courts are heard here. It is the final court of appeal for the granting or refusal of injunctions.

THE HOUSE OF LORDS

The highest court of appeal in the United Kingdom is the House of Lords, hearings by the Law Lords are concerned solely with questions of law of public importance.

OTHER COURTS AND TRIBUNALS

CORONERS’ COURTS

Although the power of coroners’ courts is now weaker than when they were established in 1194, they still have an influential part to play in matters relating to deaths other than by natural causes. Any death that is sudden, unexplained or unnatural or that occurs as a result of violence has to be reported to a coroner. Coroners are either lawyers or doctors, and sometimes both, and their role is to hold inquests to determine the identity of the dead person and how, when and where death occurred. A coroner sometimes sits with a jury, whose verdict determines the outcome of the inquiry. In addition to inquests into deaths, coroners also determine whether or not treasure has been found.

INDUSTRIAL TRIBUNALS

Claims of unfair dismissal, for redundancy payments and compensation payments are heard by industrial tribunals. They are not ‘courts’ though they do have quite extensive powers. They deal also with cases of sexual and racial discrimination. They are usually open to the press and the public. Other tribunals include the lands tribunal, industrial injuries board, pensions board and tax commissioners.

THE LEGAL PROFESSION

SOLICITORS

The legal profession is dual in nature; lawyers are either solicitors or barristers though occasionally both, but can pursue only one or other profession at any one time. Although the distinction is becoming increasingly blurred, in general terms solicitors, with whom the public deals directly, tend to handle non-litigious matters such as conveyancing and the drafting of wills and administration of estates. They are instructed by their clients directly and do not have a general right of appearance in all the courts. They are controlled by the Law Society.

BARRISTERS

Barristers are known as counsel and spend most of their time advising on points of law or as advocates in the higher courts, where they have a partial monopoly and appear in wigs and gowns. Solicitor advocates wear gowns but not wigs. Barristers are not employed by the public directly but through a solicitor. After being ‘called to the Bar’ they are responsible for their professional conduct to the Inn of Court which has called them.

THE LAW OFFICERS

THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

The Attorney General is a Queen’s Counsel (QC) and the government’s chief legal officer. He is a politician as well as a lawyer and a member of the ruling political party. Normally his permission has to be sought to start proceedings for contempt of court, treason and other serious constitutional issues.

THE LORD CHANCELLOR

He also is a politician, a member of the Cabinet of the governing party and is appointed by the Prime Minister. The Lord Chancellor is head of the judiciary and Speaker of the House of Lords.

DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS

This office-holder is a civil servant, not a politician, and heads the Crown Prosecution Service, whose role is to bring prosecutions on behalf of the Crown, having first consulted and advised the police on such matters as the evidence and the strength of the case.

2

It’s a matter of reputation

INTRODUCTION

All people are entitled to their reputations whether they are good, bad or indifferent, and the laws of defamation exist to protect such reputations from unjustified or unwarranted attacks. Consequently it is vitally important that every journalist, whether working as a freelance or as a member of staff, whether as a writer or a production specialist, has a thorough knowledge and understanding of what such laws provide and how they can influence a journalist’s day-to-day activities.

The real skill in journalism does not show simply in the cleverness of the ways of defending an action for defamation once it has been published, but in recognising a possible problem before publication, and then in handling it in such a way that any complaint after publication can be successfully rebutted or defended.

The maxim should be: ‘If in doubt find out’ rather than ‘If in doubt leave it out’, because a great deal of potentially damaging but justifiable public interest journalism can be published once the possible legal pitfalls have been recognised and avoided.

The law seeks a balance between a person’s right to defend his reputation on the one hand and the defence of the freedom of speech and expression on the other.

WHAT IS A DEFAMATORY STATEMENT?

There is no one adequate and comprehensive definition of words or pictures that are defamatory, and journalists must consider the explanations used by judges when addressing juries over the past hundred years or more to glean from them the kinds of statements that are likely to be considered injurious.

The basic definition was given by a judge in 1840 when he described a defamatory statement as:

A publication…which is calculated to injure the reputation of another by exposing him to hatred, contempt or ridicule.

Since that time other judges have developed and elaborated on this definition. In 1924 Lord Justice Scrutton said that words

may damage the reputation of a man as a business man, which no one would connect with hatred, ridicule, or contempt.

In 1934 the same judge referred to words by Mr Justice Cave in 1882, who said:

The law recognises in every man a right to have the estimation in which he stands in the opinion of others unaffec...