![]()

Part One

Region and Context

![]()

1

Introduction: tourism South and Southeast Asia-regin and context

C. Michael Hall and Stephen Page

Private sector debt is now equivalent to twice the region’s annual economic output

(Saludo and Shameen, 1998).

Introduction

The Asian economic crisis of 1997 and 1998 focused the world’s attention on the region as never before. Images of dramatic currency and stock market collapse, loss of foreign reserves and political instability have reverberated around the globe, dramatically affecting policy and investment decisions as well as tourist flows.

The changes in the region and their effects on confidence in the global economy reflect the increasing globalization, not only of the economy, but also of communication, information and tourism. In recent years, Asia has become a region of major importance in the world economy and has become increasingly integrated with the economies of Europe and North America. Furthermore, there has been an intensification of intraregional linkages as trade and investment within the region have grown (Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), 1997; Hall, 1997). Nevertheless, with growth came problems. Levels of debt increased dramatically. Loose monetary policy and over-eager borrowers and lenders pouring unprecedented amounts of credit into property, industry and financial assets bankrolled a bubble economy which finally collapsed. When the collapse in property prices in Thailand in 1997 prompted foreign creditors to call in loans to Thai banks and businesses, the resultant need for hard currency and the subsequent devaluation of the baht led to a financial meltdown which reverberated throughout the region, forcing countries such as Indonesia and Thailand to sign up for International Monetary Fund (IMF) loans and programmes (Saludo and Shameen, 1998). Devaluation, debt and the forced deregulation of many parts of national economies have led to the contraction of many economies and the threat of a sustained period of recession marked by greater unemployment, greater political instability, possible food shortages in the case of Indonesia and likely even less attention to the need to prevent environmental degradation.

In this environment tourism – for long one of the mainstays of the region’s economy, accounting for 10.3 per cent of Asia’s GDP (Bacani, 1998)- has now become an even more important source of economic development and foreign exchange, as well as a mechanism for employment generation. As Hitchcock et al. (1993: p. 1) reported

the phenomenal growth in tourism in S.E. Asia, as elsewhere in the developing world, has been associated with a number of factors and processes. One of the more important of these has been an increase in peoples ability to afford to travel to the region. This may be attributed to parallel factors: first, rising levels of affluence in the main sources areas, and second, the steadily falling cost, in real terms, of travel to the region.

Until the onset of the Asian financial crisis (World Tourism Organization 1999), the region was also developing as a major source of outbound tourism. Intraregional travel is still significant, though the decline in the region’s economies has meant that regionally generated inbound tourism has deflated across the region. Inbound tourism from outside the region has therefore become extremely valuable – and extremely competitive. The decline in the value of the region’s currencies in relation to major tourism-generating regions of North America, Europe, and even Australia, Japan and New Zealand, has meant that, apart from external perceptions of instability in some cases, the region has become an extremely attractive destination in terms of exchange rates.

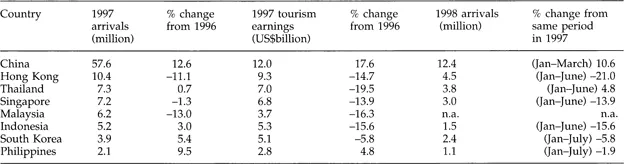

Table 1.1 illustrates some of the fluctuations in tourism numbers which have occurred in the region in 1997 and the first half of 1998. Within the region only Thailand, which has taken a very aggressive stance in attracting tourists, and China have shown substantive tourist growth. Although, in the case of China it should be noted that growth has occurred because of increased arrivals from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macau, with arrivals outside these markets actually dropping by 2.2 per cent in the first quarter of 1998.

Table 1.1 Fluctions in arrivais Asian destinations 1997 and 1998

Note

n. a., not available

Source: various

These dramatic fluctuations, and their wider significance beyond tourism, graphically illustrate the need for a contemporary assessment of tourism in what has been one of the most dynamic regions for the industry over the past two decades. Although, as Qu and Zhang (1997) suggest, it is impossible to take full account of future events as tourism markets within the region are far from mature, unpredictable and, in some cases, unstable (as the discussion of visitor arrivals in different chapters suggest), it is nevertheless vital that students of tourism are aware of the factors and issues which are shaping the region’s future, not only in tourism but in its wider political, economic, social and environmental context. This first chapter, and the following series of overview chapters on tourism in the region, therefore provide the context within which the chapters on national tourism should be seen.

Southeast Asia as a region

For any study of a region such as Southeast Asia, it is important to establish the geographical frame of reference and, in simple terms, what is the regional context. According to Dwyer (1990: p. 1) ‘it is something of a paradox that although the concept of South East Asia as a geographical region is relatively recent, in terms of international relationships its significance in the world today is profound’. This somewhat sweeping statement illustrates that Southeast Asia is a region that was created in international and political terms in the post-war period because ‘Before world war II South East Asia was scarcely even a geographical expression. For the West, it was little more than an undifferentiated part of Monsoon Asia, the teeming eastern and southern margins of the great Asian continent; for Asians themselves it had no significance at all’ (Fryer, 1970: p. 1).

One of the most influential studies of the postwar period was Fisher’s (1962) assessment of Southeast Asia as the Balkans of the Orient, in which he depicted the region as an area of transition, geographic variation and potential instability. In the post-war period, Fisher (1962) identified the implications of post-colonial transition, from subjugation under colonial rule to nation status, where many states contained an enormous diversity of population with varied cultures and religions. Fisher highlighted the role of economic development in determining the political future of most states. In his highly influential 831 page seminal study on Southeast Asia, Fisher (1964) depicts the spatial delimitation of Southeast Asia in that

it is only since the second world war that the term South-east Asia has been generally accepted as a collective name for the series of peninsulas and islands which lie to the east of India and Pakistan and to the south of China. Nor is it altogether surprising that the West should have been slow to recognise the need for some common term for this area, which today comprises Burma [Myanmar], Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, the Federation of Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Indonesia and the Philippines (Fisher, 1964: p. 3).

In fact, one of the unifying features which explains the common development histories of many of the countries within the region is their different imperial groupings (with the exception of Thailand), with terms such as Further India, Far Eastern Tropics and Eastern Asia previously used to identify the region.

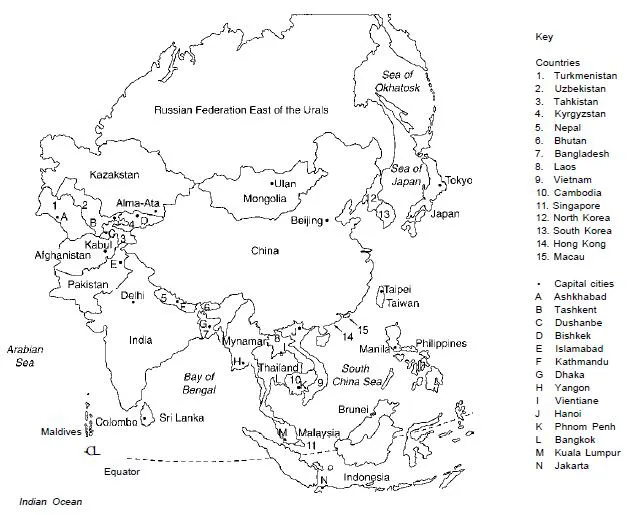

For the purpose of this book, Fisher’s poignant comments of 1964 (p. 5) still hold true in that ‘from a geographical point of view South East Asia must be accounted a distinctive region within the larger unity of the Monsoon lands … and worthy to be ranked as an intelligible field of study on its own’. However, in terms of the geographical context of the region, this book incorporates a number of countries from the margins of the monsoon lands to extend the scope to South and Southeast Asia, with Fisher’s (1964) designation extended to include Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan (Figure 1.1), because too little research on and knowledge of the region has been disseminated, even though Fisher (1964) rightly debated the logic of Sri Lanka being incorporated under the heading Southeast Asia (Ceylon was the strategic location of the Southeast Asia Command during the Second World War).

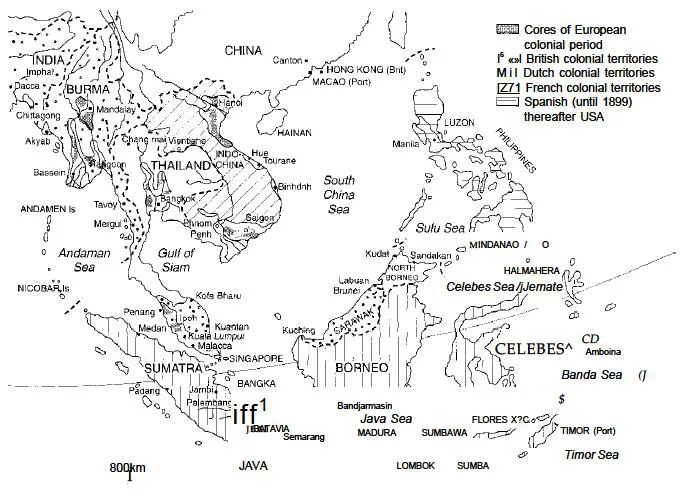

Kirk (1990) explored the colonial past of Southeast Asia, building on the excellent historical analysis of the region’s development by Fisher (1964), to indicate that a series of core areas developed prior to and during the period of European colonization (1500–1950). These core areas were largely established prior to European rule and accentuated the existing forms of core and periphery so that a series of

Figure 1.1 The regional context

patterns emerged as illustrated in Figure 1.2. Kirk (1990) examined the core areas in Thailand, British Burma, India, the Malayan west coast, Dutch Indonesia and French Indochina. These processes of colonization did little to reduce regional inequalities. In fact, Dixon and Smith (1997: p. 4) argue that

The incorporation of Southeast Asia into the emergent global capitalist system took place under the auspices of colonial economic and, except for Thailand, political control. By the end of the colonial period for much of Southeast Asia an extremely uneven pattern of development had emerged. The post-colonial states were characterised by high levels of ethnic diversity, limited national integration, little contact with their neighbours, unbalanced urban hierarchies and unevenly developed economies, both spatially and by sector. These situations have had a profound impact on both the subsequent development of the regions economies and on economic policies that have followed.

Thus, the decolonization era saw many of the former colonies become nation states with very little adjustment of political boundaries. Likewise, many of the new states inherited the development problems of the former colonies, not the least of which were related to the divisive social structures fostered by former colonies. In economic terms, Kirk (1990: pp. 44–45) argued that, following the colonial era, ‘over-dependence on a few commodities to earn foreign exchange … [with] …

Figure 1.2 Cores of the European colonial period (redrawn and modified from Kirk, 1990)

foreign capital still prominent in new forms of dependency’. This virtually encouraged a greater core-periphery pattern of neo-colonial development. In fact, ‘the core infrastructures built during the colonial era, have provided the main attraction to new industrial and commercial developments, and central governments, whatever their political policies and ideals’ (Kirk, 1990: pp. 45–46). This point is developed by Dixon and Smith (1997: p. 5) who argue that

the emergence and/or intensification of core areas during the colonial era was closely associated with the development of a series of major port cities -Bangkok, Jakarta, Manila, Rangoon, Saigon-Cholon and Singapore. These centres became the major focus for their respective national economies and the principal interface with the international economy. The emergence of these major cities has resulted in the South East Asian region exhibiting high levels of urban primacy and remarkably unbalanced urban hierarchies.

Therefore, in any discussion of the Southeast Asian region two fundamental features of the social, economic and political landscape need to be considered: the population and its distribution and the related theme of urbanization, since each has continued to lead to greater concentrations of economic activity around the core areas. As a result, any discussion of tourism, its development and use of infrastructure and the social and cultural landscape needs to pay attention to the existing patterns of development.

Population, economic development and the space economy in Southeast Asia: megacities, extended metropolitan regions and globalization

The population of any country, comprises the basic human resource for the development of economic activity and, in tourism, is the manpower and labour component. Dixon (1990) provides a detailed analysis of the demographic structure and cultural influences impacting upon the population of Southeast Asia (e.g. the distribution of native people and languages), much of which is drawn from the classic study of the region by Fisher (1964, and subsequent editions). Hull (1997) described the recent population, where variations in mortality and fertility rates occur throughout the region. The cultural geography of the area is also an important backdrop to the discussion of the development of plural societies in the region, particularly during colonization, and the concept of cultural clusters where nations were created with little attention to the cultural distribution of population. Likewise, the policies of colonial powers which actively encouraged the inward migration of Chinese labour to many parts of the region in the nineteenth century, followed by migrants from the Indian sub-continent, created plural societies. This also created a host of political and racial issues for the postcolonial powers, and some of these political and rac...