![]()

Chapter 1

Ancient and Classical: Egypt, Greece, and Rome

The symbolism of the pyramid

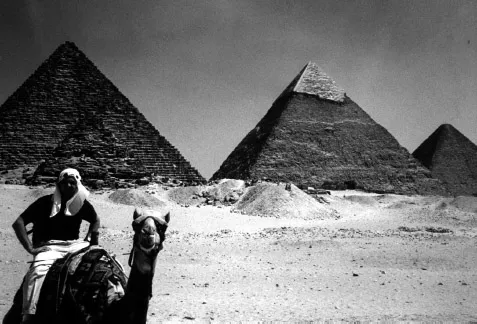

In the Egyptian pyramid, as in the Pyramids at Giza—Cheops, Chefren, and Mykerinos (Figure 1.1), from 2589 to 2504 BC—the massive structure of blocks is far in excess of the function of the structure as a tomb. The goal was to create a symbolic architecture in relation to the heavens and constellations, which contradicts the functional requirements of the buildings. Cheops means “region of light,” Chefren means “the appearance of divine light,” and Mykerinos means “the constant power of divine light” (Jacq 1998: 71). In the hypostyle hall, as in the Temple of Amon at Karnak, the forest of columns is far in excess of the requirement of supporting the roof. The goal was to create a symbolic architecture in relation to the Ennead and the passage to the other world, in contrast to the functional requirements of the building. Karnak means “heaven on earth,” and the temple was intended to be a “city of light” (p. 111).

In the sarcophagus of the Pyramid of King Unas in North Saqqara, from around 2300 BC, false doors appear on the wall to represent the doors to the afterlife, between the visible and invisible, or occult, through which only the spirit can cross. The vocabulary element in the syntax of the visual form of the architecture, the door, is placed out of context to represent a metaphorical idea. The vault of the sarcophagus, as in many temples, is painted with five-pointed stars, representing the abode of the departed soul. The vault of the building doubles as the metaphorical vault of the heavens; the architecture is a catechism of a cosmology or structure of being. The hieroglyphs on the walls of the sarcophagus are called the Unas Funerary Texts or Texts of the Pyramids. The text of the hieroglyphs contains a description of a pyramid: “I have walked on your rays as if on a stair of light to ascend to the presence of Ra … heaven has made the rays of the sun solid so that I can elevate myself up to the eyes of Ra … they have built a staircase leading to the sky by which I can reach the sky” (Carpiceci 1997: 53). The pyramid is intended as a metaphorical stairway from earth to heaven and Ra, the god of light and the sun. The actual staircase in the architectural syntax doubles as a metaphorical staircase, a metaphysical concept, which the architecture is able to convey outside its functional requirements, because the actual staircase does not lead anywhere, and the form contradicts the function.

Figure 1.1 Pyramids at Giza, 2589–2504 BC

The apex of the pyramid represented the sun, as the unitary source from which all things emanate, what the Alexandrian Plotinus (204–70) would call “the One.” The apex of the pyramid was gilded, to reflect the light of the sun and to appear as the sun. The base of the pyramid, a square in plan, represented the material world, as the material world is always represented by the number four—four corners, four seasons, four cardinal points, etc. The edges of the pyramid are the rays of light from the sun in the formation of the matter of the material world. Among the polyhedral atoms of the elements of Plato, the atom of earth was a cube, and the atom of fire was the tetrahedron (a three-sided pyramid). In cosmologies from the Classical world to the Renaissance, matter originates in an incorporeal and inaccessible light, and unfolds in a geometrical progression from point to line to surface to solid. The point is the closest thing to the immaterial in the material world.

As matter comes to being from an unknowable source, the soul exits the material world toward an unknowable destination through the door to the afterlife, in a circuitus spiritualis, or infinite cycle of being, as represented by the uroborus serpent eating its own tail, which can be found on the walls surrounding the necropolis at Saqqara. The circuitus spiritualis is enacted by the architectural vocabulary elements: entrance, exit, descent, and ascension are movements enacted by architectural space. It can be argued that the movements enacted by architectural space themselves are metaphors to begin with, in that architectural space is a metaphor. Architecture defines a certain space, but the space only exists as it is defined by the architecture. Even though a space is defined by architecture, space can still only be seen as indivisible, therefore its material existence can be questioned, and it is more easily understood as a concept projected onto the material world by the human mind, as Kant established. Architecture, space, and movement in architectural space therefore occur only metaphorically, as elements of architecture as a form of artistic expression, or an idea in the mind of the viewer.

Ra, the god of light, was one of the three primary gods of Egyptian cosmology, the other two being Amon, the “hidden one,” representing that which is inaccessible, and Ptah, god of creation and the material world. The three gods were the three manifestations of a unitary principle, and appear to be a precursor to the Christian Trinity, where the Father is inaccessible, the Spirit is light, and the Son is the body, representing the same hypostases of being as the Egyptian pyramid. In the Book of the Dead, the hieroglyphic text of the Egyptian afterlife, the soul of the departed is weighed by Anubis, the guardian of the dead, and judged by Maat, the goddess of justice. If the soul is heavier than a feather, the body of the departed is eaten by Ammit, female demon and Devourer of the Dead; if the soul is lighter, the departed is escorted by Anubis to the throne of Osiris, who sits in judgment as lord of the underworld. The concept reappears in Christian iconography: while the Pantokrator Christ sits enthroned in judgment, the soul of the departed is weighed in purgatory by Michael and Mary. The weighing of the soul in the Book of the Dead is recorded by Thoth, or Hermes Trismegistus, inventor of writing, hieroglyphs, and philosophy. The passage though the underworld, or the circuitus spiritualis, enacted by architectural space, is connected to the origin of writing. The word, or logos, is the spiritual made physical; the emanation theory of light is connected to writing also. The origin of writing is thus connected to architectural space, as the formation of an immaterial idea in the mind made physical in the material world. The grouping of three into one is found throughout the architecture of the pyramids and temples in Egypt.

The three pyramids at Giza correspond in their configuration to three stars at the center of Orion’s Belt, so that the pyramids would enact “Heaven on earth,” as Egypt was thought to be. Orion’s Belt was the celestial residence of the soul of Osiris, god of the underworld. The pyramids are a cosmology of the universe, and they connect earth and heaven, life and death, in the circuitus spiritualis, symbolized by Ra in a solar boat on Nun, the primordial ocean, rolling a sun disk, which is manifested in the material world by a black scarab beetle rolling a ball of its dung along the ground, from which eggs are hatched before the sun disk is received by Osiris in the underworld. The material world and nature are rationalized in relation to abstract concepts of space, and metaphors for the creation process, in order to be seen as part of a cosmology.

The pyramid later played a role in theories of creation and vision itself in the Renaissance. In the Theologia Platonica, written between 1469 and 1474, Marsilio Ficino proposed an intromission theory of vision in which rays of light projected by the sun emanate in the form of a cone or pyramid if they pass through a small hole on a plane (as it would be in a camera obscura). As rays of light from the sun pass through a hole in the pupil of the eye, they emanate in the same way in the form of a cone or pyramid into the soul, acting as a lens or pineal gland, or camera obscura, as a mirror to what is perceived. Leon Battista Alberti, in his treatise on painting, De pictura, in 1435, also proposed a theory of vision in which rays of light were arranged in a pyramid. Surfaces of material objects are defined and measured by rays of light, which translate visual matter into intelligible matter, giving it the qualities of proportion, arrangement, and measurement. Matter is understood through light, and at the same time light makes the intelligible material, in the process of creation from the originary light, as represented by the pyramid in Egypt.

In the De anima, Aristotle compared the active intellect, the cosmic intellect, that which actualizes human thought and perception, in an entelechy, to light itself, in relation to the potential or material intellect, the nous hylikos: “light makes potential colors actual” (3.5.430a10–25) (Davidson 1992: 19). The active intellect, as light, illuminates what is intelligible in the sensible world. Commentators on Aristotle, such as Abu Nasr Alfarabi (870–950), in his Risala (pp. 25–7), or De intellectu, in the tenth century, described the light of the sun, following Aristotle in De anima (2.7.418b9–10), as making the corporeal eye, or potential vision, transparent or illuminated, in the same way that active intellect illuminates potential intellect. Potential colors become actually visible, and potential vision becomes actual vision. Active intellect makes potential intellect transparent, as light is infused into the oculus mentis, and the transparency of light and color illuminates the intellect through vision. In the Risala, “as the sun is that which makes the eye sight in actuality and visible things visible in actuality, insofar as it gives illumination, so likewise the agent intellect is that which makes the intellect which is in potentiality an intellect in actuality insofar as it gives it of that principle” (Alfarabi 1967: 218–19).

According to Alberti, only certain rays of light define the outline, measure and dimension of surfaces, the “extrinsic rays.” The extrinsic rays define the outline of the pyramid of light in vision. The pyramid is formed between the surface of the material object and the eye, which is also the source of an inner light, in extramission. As Alberti says, “The base of the pyramid is the surface seen [as the base of the Egyptian pyramid represents matter], and the sides are the visual rays we said are called extrinsic. The vertex of the pyramid resides within the eye [the light originating from the eye corresponds to the originary light in creation], where the angles of the quantities in the various triangles meet together” (Alberti 1972 [1435]: I.7). The pyramid of light encloses the “median ray,” which is variable and absorbs light and color. The median ray extends between the vertex of the pyramid and the surface of the matter, and fills in the color and shadow found within the outline of the matter. The “centric ray” in the center of the pyramid is the strongest of the median rays, and forms a direct line from the vertex of the pyramid to the center of the surface, exactly perpendicular to the surface. The position of the centric ray, along with the distance of the ray from the vertex, determines the location of the outline of the surface.

Following Alberti, Piero della Francesca, in De prospectiva pingendi, in around 1480, described the extrinsic rays in the pyramid of vision as lines which emanate from the extremities of the material object and reach the eye, in between which the eye perceives the material object and transforms it into an intelligible object, as potential intellect and vision are activated by active intellect (Francesca 1942: 64). The border of the object is described by the rays of light of the eye, in extramission, in proportion and measure, that is, as an intelligible object. The borders of the material object, established through measure and proportion by the extrinsic rays from the eye, determine how things diminish in size in relation to the eye, corresponding to the sharpness of the angle in vision. It is thus necessary to understand the linear qualities of objects in a picture plane so that they can be represented in a painting, as copies of the patterns of intelligible objects. The pyramid is a necessary tool for Piero in the conception of a visual image, whether in the mind or reproduced on a painted surface. The pyramid is a primordial form in the architectonic, or architecture, of thought and perception.

Intersecting triangles (they were referred to as pyramids) were used as diagrams of processes of vision, and they were used as diagrams of the process of creation, in the coincidence of opposites, as vision and intellection were often seen in relation to creation, based in Hermetic, or Egyptian, philosophy. A diagram of intersecting pyramids or triangles was used by Nicolas Cusanus in his De coniecturis, or On Conjecture, begun in 1442. Cusanus described the intersecting pyramids as figura paradigmatica. The base of the pyramid of Cusanus is the darkness of primordial origin, the ocean of chaos (Nun), while the apex is the originary, unitary, incorporeal light, as in the Egyptian pyramid. In between the base and the apex is found all created matter, as in the theories of vision of Alberti and Piero. The intersecting pyramids of Cusanus are divided into the hypostases of being—the terrestrial, celestial, and supercelestial realms—as in the trinity of Egyptian gods, Ptah, Ra, and Amon, and the architecture of the pyramids in Egypt. As the pyramids of Cusanus intersect, unity is everywhere contained in alterity and alterity is everywhere contained in unity, in the circuitus spiritualis between the ineffable source and the material world, and a coincidentia oppositorum. Human knowledge, represented by geometrical forms, is a product of the emanation of light from the One, represented by unitary form, the point or apex, though knowledge of the One is impossible, as in Plotinus.

According to Cusanus, the human mind reproduces the mind of God, the active intellect, in the forming of conjectures, or concepts and judgments, in nous poietikos, as activated by active intellect. Conjecture should proceed from the human mind as the material world proceeds from divine intelligence (Cusanus 1972 [1443]: I.1.5), in the same way that the light from the human eye corresponds to the originary light, and the intelligible becomes material as the material becomes intelligible, in the action of the intersecting pyramids.

Athanasius Kircher began publishing in 1631, and arrived in Rome in 1634, the same year that Francesco Borromini began his design of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane. Kircher was brought to Rome from Avignon at the recommendation of Cardinal Francesco Barberini to assume the Chair of the Mathematics Department at the Collegio Romano. Kircher’s first significant publications were the Primitiae Gnomicae Catoptricae of 1633 and the Prodromus Coptus Sive Aegyptiacus of 1636. Kircher also wrote about such diverse subjects as magnetism, astronomy, perspectival construction, geology, and music. His most important works concern the philosophical and theological origins of Christianity and Neoplatonism in ancient Egypt, incorporating symbolic interpretations of hieroglyphs, published in conjunction with his collaboration with Gianlorenzo Bernini on the design of the obelisks erected in Piazza Navona and Piazza Minerva: Obeliscus Pamphilius, Oedipus Aegyptiacus, and Obeliscus Aegyptiacus.

The De coniecturis of Cusanus was well known to Athanasius Kircher in Rome, who copied passages from it in his own writing, and reproduced the intersecting pyramids, as paradoxical figures of light and dark, representing the progression from unity to alterity and alterity to unity. Intersecting pyramids also appear in the Microcosmi Historia of Robert Fludd, published in Oppenheim by Johannes Theodore de Bry in 1619. Fludd’s Microcosmi Historia was also known to Kircher, who appropriated many of its ideas. Corresponding to the celestial hierarchies, the nine levels of angels that mediate between human intelligence and God, Fludd conceived of the universe as composed of three triangles or pyramids (body, soul, and spirit) divided into three parts each (terrestrial, celestial, and supercelestial), reiterating the hypostases of ancient Egypt. The pyramids proceed from the apex of the spirit, simplicity, and unity, to the base of matter, complexity, and alterity. The procession is created by light from the sun, which divides the world in substantial parts. In the diagram of intersecting pyramids, the base of the pyramid of light is the Trinity, represented as the sun, and the base of the pyramid of darkness is primordial unformed matter, the Aristotelian substrate, represented as the earth. Intersecting pyramids of light and darkness appear in Kircher’s Prodromus Coptus Sive Aegyptiacus in 1636, and in his Obeliscus Pamphilius and Musurgia universalis in 1650.

The diagrams of intersecting pyramids in the manuscripts of Fludd and Kircher correspond to the creation myth of Pimander from the Corpus Hermeticum, compiled by Marsilio Ficino and translated into Latin in 1471, thought to be the writings of Hermes Trismegistus, the originator of philosophy in Egypt, though as it turned out the writings were done by later Platonic philosophers. Cosimo de’ Medici commissioned Ficino to translate the Greek manuscript which had been brought to Florence in the Renaissance, which described the creation of the world and the ascension of the soul through the hypostases of being. Hermes Trismegistus was thought to be the most ancient source of wisdom in Ficino’s Theologia Platonica. Ficino’s translation of the Corpus Hermeticum, entitled the Pimander after the first of the Hermetic dialogues, had a widespread influence in Renaissance art and philosophy.

In the Book of Ascleplus of ...