- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This classic work has inspired and informed a whole generation of artists and technicians working in all branches of the audio industry. Now in its seventh edition, The Sound Studio has been thoroughly revised to encompass the rapidly expanding range of possibilities offered by today's digital equipment. It now covers: the virtual studio; 5.1 surround sound; hard drive mixers and multichannel recorders; DVD and CD-RW.

Alec Nisbett provides encyclopaedic coverage of everything from acoustics, microphones and loudspeakers, to editing, mixing and sound effects, as well as a comprehensive glossary.

Through its six previous editions, The Sound Studio has been used for over 40 years as a standard work of reference on audio techniques. For a new generation, it links all the best techniques back to their roots: the unchanging guiding principles that have long been observed over a wide range of related media and crafts.

The Sound Studio is intended for anyone with a creative or technical interest in sound - for radio, television, film and music recording - but has particularly strong coverage of audio in broadcasting, reflecting the author's prolific career.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Audio techniques and equipment

If you work in a radio or recording studio, or with television or film sound; if you are in intimate daily contact with the problems of the medium; if you spend hours each day consciously and critically listening, you are bound to build up a vast body of aural experience. Your objective will be to make judgements upon the subtleties of sound that make the difference between an inadequate and a competent production, or between competent and actively exciting – and at the same time to develop your ability to manipulate audio equipment to mould that sound into the required shape.

The tools for picking up, treating and recording sound continue to improve, and it also becomes easier to acquire and apply the basic skills – but because of this there is ever more that can be done. Microphones are more specialized, creating new opportunities for their use. Studio control consoles can be intimidatingly complex, but this only reflects the vast range of options that they offer. Using lightweight portable recorders or tiny radio transmitters, sound can be obtained from anywhere we can reach and many places we cannot. By digital techniques, complex editing can be tackled. In fact, home computers can now simulate many of the functions of studios.

But however easy it becomes to buy and handle the tools, we still need a well-trained ear to judge the result. Each element in a production has an organic interdependence with the whole; every detail of technique contributes in one way or another to the final result; and in turn the desired end-product largely dictates the methods to be employed. This synthesis between means and end may be so complete that the untrained ear can rarely disentangle them – and even critics may disagree on how a particular effect was achieved. This is because faults of technique are far less obvious than those of content. A well-placed microphone in suitable acoustics, with the appropriate fades, pauses, mix and editing, can make all the difference to a radio production – but at the end an appreciative listener’s search for a favourable comment will probably land on some remark about the subject. Similarly, where technique is faulty it is often, again, the content that is criticized. Anyone working with sound must develop a faculty for listening analytically to the operational aspects of a production, to judge technique independently of content, while making it serve content.

In radio, television or film, the investment in equipment and the professionals’ time makes slow work unacceptable. Technical problems must be anticipated or solved quickly and unobtrusively, so attention can be focused instead on artistic fine-tuning, sharpening performance and enhancing material. Although each individual concentrates on a single aspect, this is geared to the production as a whole. The first objective of the entire team is to raise the programme to its best possible standard and to catch it at its peak.

This first chapter briefly introduces the range of techniques and basic skills required, and sets them in the context of the working environment: the studio chain or its location equivalent. Subsequent chapters describe the nature of the sound medium and then elements of the chain that begins with the original sound source and includes the vast array of operations that may be applied to the signal before it is converted back to sound and offered to the listener – who should be happily unaware of these intervening stages.

Studio operations

The operational side of sound studio work, or for sound in the visual media, includes:

● Choice of acoustics: selecting, creating or modifying the audio environment.

● Microphone balance: selecting suitable types of microphone and placing them to pick up a combination of direct and reflected sound from the various sources.

● Equalization: adjusting the frequency content.

● Feeding in material from other places.

● Mixing: combining the output from microphones, replay equipment, devices that add artificial reverberation and other effects, remote sources, etc., at artistically satisfying levels.

● Control: ensuring that the programme level (i.e. in relation to the noise and distortion levels of the equipment used) is not too high or too low, and uses the medium – recording or broadcast – efficiently.

● Creating sound effects (variously called foley, hand or spot effects) in the studio.

● Recording: using tape, disc and/or hard disk (including editing systems and back-up media) to lay down one, two or more tracks.

● Editing: tidying up small errors in recordings, reordering or compiling material, introducing internal fades and effects.

● Playing in records and recordings: this includes recorded effects, music discs or tapes, interviews and reports, pre-recorded and edited sequences, etc.

● Feeding output (including play-out): ensuring that the resultant mixed sound is made available to its audience or to be inscribed upon a recording medium with no significant loss of quality.

● Documentation: keeping a history of the origins, modification and use of all material.

● Storage: ensuring the safety and accessibility of material in use and archiving or disposing of it after use.

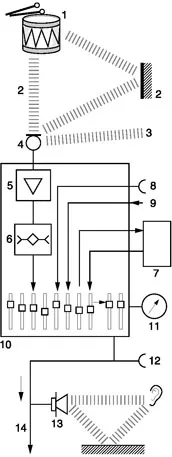

[1.1] Digital studio chain

1, Microphones. The electrical signal from a microphone is analogue, so it has to be fed through an analogue-to-digital (A/D) converter, after which it remains digital throughout the chain.

2, igital console (mixer).

An alternative is a personal computer (often, for media applications, a Mac) with audio software that includes a pictorial representation of faders, plus ‘plug-ins’. 3, Modular digital multitrack eight-track recorders (MDMs): these can be linked together to take up to 128 tracks, although 32 are generally more than enough. Here the alternative is hard disk recording. 4, Digital audio tape (DAT) recorder. 5, Digital audio workstation (DAW – more software on a personal computer). 6, CD-R (or DVD-R) usually built in to the computer. 7, The end-product on CD.

In small radio stations in some countries, a further responsibility may be added: supervising the operation of a transmitter at or near the studio. This requires certain minimal technical qualifications.

The person responsible for balancing, mixing and control may be a sound or programme engineer, or balance engineer (in commercial recording studios); in BBC radio is called a studio manager; in television may be a sound supervisor; on a film stage is a sound recordist (US: production sound recordist); or when re-recording film or video, a re-recording mixer (US) or dubbing mixer (UK).

Although in many parts of the world the person doing some of these jobs really is an engineer by training, in broadcasting – and for some roles in other media – it is often equally satisfactory to employ men and women whose training has been in other fields, because although the operator is handling technical equipment and digital operations, the primary task is artistic (or the application of craftsmanship). Real engineering problems are usually dealt with by a maintenance engineer.

Whatever title may be given to the job, the sound supervisor has overall responsibility for all sound studio operations and advises the director on technical problems. Where sound staff work away from any studio, e.g. on outside broadcasts (remotes) or when filming on location, a higher standard of engineering knowledge may be required – as also in small radio stations where a maintenance engineer is not always available. There may be one or several assistants: in radio these may help lay out the studio and set microphones, create sound effects, and make, edit and play in recordings. Assistants in television and film may also act as boom operators, positioning microphones just out of the picture: this increasingly rare skill is still excellent training for the senior role.

The sound control room

In the layout of equipment required for satisfactory sound control, let us look first at the simplest case: the studio used for sound only, for radio or recording.

The nerve centre of almost any broadcast or recording is the control console – also known as desk, board or mixer. Here all the different sound sources are modified and mixed. In a live broadcast it is here that the final sound is put together; and it is the responsibility of the sound supervisor to ensure that no further adjustments are necessary before the signal leaves the transmitter (except, perhaps, for any occasional automatic operation of a limiter).

The console, in most studios the most obvious and impressive capital item, often presents a vast array of faders, switches and indicators. Essentially, it consists of a number of individual channels, each associated with a particular microphone or some other source. These are all pre-set (or, apart from the use of the fader, altered only rarely), so that their output may be combined into a small number of group controls that can be operated by a single pair of hands. The groups then pass through a main control to become the studio output. That ‘vast array’ plainly offers many opportunities to do different things with sound. Apart from the faders, the function of which is obvious, many are used for signal routing. Some allow modification of frequency content (equalization) or dynamics (these include compressors and limiters). Others are concerned with monitoring. More still are used for communications. Waiting to be inserted at chosen points are specialized devices offering artificial reverberation and further ways of modifying the signal. All these will be described in detail later.

[1.2] Components of the studio chain

1, The sound source. 2, Direct and indirect sound paths. 3, Noise: unwanted sound. 4, Microphone. 5, Preamplifier. 6, Equalizer. 7, everberation, now usually digital. 8, ape head or disc player. 9, External line source. 10, Mixer. 11, Meter. 12, Recorder. 13, Loudspeaker: sound reaches the ear by direct and reflected paths. 14, Studio output.

In many consoles, the audio signal passes first through the individual strips (‘channels’), then through the groups, then to the main control and out to ‘line’ – but in some this process is partly or wholly mimicked. For example, a group fader may not actually carry the signal; instead, a visually identical voltage control amplifier (VCA) fader sends messages which modify the audio in the individual channels that have been designated as belonging to the group, before it is combined with all other channels in the main control. In some consoles, the pre-set equalization, dynamics and some routing controls are located away from the channel strips, and can all be entered separately into the memory of a computer: this greatly reduces the (visual) complexity and total area of the layout.

In the extreme case, the actual signal does not reach the console at all: the controls send their messages, via a computer, to racks in which the real signal is modified, controlled and routed. What then remains of an original console layout depends on the manufacturer’s judgement of what the customer will regard as ‘user friendly’: it should be possible for the majority of users to switch between analogue and fully digital systems (and back again) without having to go through a major course of re-education.

Apart from the microphones and control console, the next most important equipment in a studio is a high-quality loudspeaker system – for a radio or recording studio is not merely a room in which sounds are made and picked up by microphone, it is also the place where shades of sound are judged and a picture is created by ear.

The main thing that distinguishes a broadcasting studio from any other place where microphone and recorder may be set up is that two acoustically separate rooms must be used: one where the sound may be created in suitable acoustics and picked up by microphone, and the other in which the mixed sound is heard. This second room is often called the control room – although in organizations where ‘control room’ means a line-switching centre it may be called a ‘control cubicle’ instead. Tape, disc and hard-drive recorders and reproducers and editing systems, and the staff to operate them, are also in the control area, as are the producer or director (in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- About the author

- 1 Audio techniques and equipment

- 2 The sound medium

- 3 Stereo

- 4 Studios and acoustics

- 5 Microphones

- 6 Microphone balance

- 7 Speech balance

- 8 Music balance

- 9 Monitoring and control

- 10 Volume and dynamics

- 11 Filters and equalization

- 12 Reverberation and delay effects

- 13 Recorded and remote sources

- 14 Fades and mixes

- 15 Sound effects

- 16 The virtual studio

- 17 Shaping sound

- 18 Audio editing

- 19 Film and video sound

- 20 Planning and routine

- 21 Communication in sound

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Sound Studio by Alec Nisbett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Acoustical Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.