![]()

SPORTS BIOMECHANICS

1 Biomechanics of

sports injury

Melanie Bussey

Knowledge assumed

Familiarity with human

anatomy

Understanding of basic

biomechanics

Introduction – the science of studying injury

Viscoelasticity and anisotropy

Skeletal muscle: maximum force and muscle activation

Ligament and tendon properties

Glossary of important terms

INTRODUCTION – THE SCIENCE OF STUDYING INJURY

BOX 1.1 LEARNING OUTCOMES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- recognise and use biomechanical terminology related to tissue function and injury

- describe the epidemiological and biomechanical perspectives of injury

- understand and explain the mechanical factors involved in tissue injury

- understand the basic material properties of human tissue

- explain the mechanical behaviours of human tissue

- understand the biomechanical functions of ligament, tendon, bone and cartilage.

For the purposes of this text we will use a simple working definition of sports injury, that is the disruption or failure of biological tissue in response to mechanical loading during sporting endeavours. To understand how injury to the musculoskeletal system occurs, it is necessary to know the loads and properties that cause specific tissues to fail. These relate to the material and structural properties of the various tissues of the musculoskeletal system: cortical and cancellous bone, cartilage, muscles, fascia, ligaments and tendons. The material properties that are important in this context are known as bulk mechanical properties. These are, for materials in general: density, elastic modulus, damping, yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, hardness, fracture resistance, fatigue strength and creep strength. It is important to understand not only how biological materials fail, but also how other materials can affect injury and how they can best be used in sport and exercise. The incidence of injury may be reduced or increased by, for example, shoes for sport and exercise, sports surfaces and protective equipment.

The study of sports injury is a multidisciplinary endeavour. Some examples of related disciplines include physiology, biomechanics, kinesiology, medicine, psychology, and epidemiology. Increasingly, the study of sports injury is also interdisciplinary, when researchers from differing disciplines combine their efforts to study injury with a new perspective. Each discipline comes with its own perspective on injury and its own specific vocabulary around injury. In this text we will be taking a distinctly biomechanical view of injury but we will also try to present data and knowledge from epidemiology and medicine to support and enrich the information given. Before undertaking any study of sports injury it is important to acknowledge the contribution of other disciplines and to understand how our biomechanical research may be informed by them.

Injury severity

From an epidemiology perspective the severity of an injury is defined by the amount of ‘time lost’. Sports injuries are considered to be any injury resulting from participation in sport or exercise that causes either a reduction in that activity or a need for medical advice or treatment. Sports injuries are often classified in terms of the activity time lost: minor (one to seven days), moderately serious (eight to 21 days) or serious (21 or more days or permanent damage). The epidemiological model varies significantly from the clinical model. From a clinical perspective, injury severity is classified by the amount of structural involvement, physical signs, and extent of dysfunction. In the clinical model, the severity increases with the amount of damage experienced by the tissue; for example, ligament injury is graded first degree (mild damage to ligament), second (moderate ligament damage) and third degree (near or complete rupture of ligament). The need for both perspectives is clear. The epidemiological perspective is necessary to understand the link between injury and exposure time; this information is important to gain insight into injury incidence, injury reoccurrence and injury outcome. In contrast, the goal for the clinical model is finding and implementing the correct treatment protocol for that injury. Both perspectives are important to the biomechanist as both present information important to understanding the mechanical mechanisms related to the injury. For example, information about exposure times gives the biomechanist insight into the nature of the loading such as frequency, loading cycle, rest time, and potential cumulative effects of loading. Information about the amount of tissue damage is important to our understanding of specific tissue tolerance and the consequence of particular load characteristics.

Mechanism of injury

The mechanism of injury refers to the physical process responsible for given damage to a body system. Broadly, an injury mechanism should establish a cause and effect relationship. Because this term is loosely defined it has been open to interpretation by many different groups that research or treat injury. Thus, categorisation of mechanisms is quite variable, yet each system seems to work for the groups that use it and may be considered correct from that group's perspective. Categorisation of mechanisms is based on a combination of description of inciting event, description of mechanical factors and tissue responses to mechanical factors. Three of the most commonly used categorisations of mechanisms of injury are shown in Table 1.1. The reason we need a method of categorising injury mechanisms is so we can better understand the causes of injury so that we may design and implement appropriate injury prevention strategies.

Table 1.1 Three of the most commonly used categorisations of mechanisms of injury

SOURCE |

LEAD BETTER (2001) | COMMITTEE ON TRAUMA RESEARCH (1985) | BAHR AND KROSSHAUG (2005) |

Contact | Crushing deformation | Description of inciting event including: |

Dynamic overload | Impulsive impact | Playing situation |

Overuse | Skeletal acceleration | Athlete–opponent behaviour |

Structural vulnerability | Energy absorption | Whole body biomechanics |

Inflexibility | Extent and rate of tissue deformation | Joint-tissue biomechanics |

Impact | |

Rapid growth | | |

Epidemiological perspective on injury

Epidemiology is the study of the incidence, distribution and determinants of disease and injury frequency within a given population (Woodward, 2005). Epidemiological studies can be descriptive or analytical. Descriptive studies examine the frequency, or incidence, and prevalence of injury occurrence. Incidence relates to the number of new cases that occur in a defined population during the time frame of the study, while prevalence refers to the total number of cases existing within a given population at a given time. Descriptive studies also look for patterns in injury occurrences by examining factors such as who gets injured, the location of injury, the time of occurrence and the type of injury. So, descriptive epidemiology provides the what, the who, the when and the where. Analytical studies examine the causal relationships for injury. So analytical epidemiologists ask the questions how and why injuries are taking place in order to establish relationships between injury occurrence and certain risk factors.

A risk factor is something that increases your chances of experiencing an injury. Sometimes, this risk comes from something you do such as not wearing a helmet while cycling. These risk factors we can manipulate to reduce our risk; they may be considered to be modifiable. At other times, there is nothing you can do; simply being of a certain age or cycling in certain weather conditions can increase your risk of injury. We cannot change our age, sex, climate etc., so these risk factors are non-modifiable.

Risk factors may also be categorised as intrinsic or extrinsic to the athlete. Intrinsic risk factors are those related to you, the athlete, specifically, such as age, sex, anatomical alignment, neuromuscular control and previous injury history. Extrinsic risk factors are those related to the sporting environment, such as use of protective equipment, climate, opponent skill or ability and rules of the game. Competing at a high standard increases the incidence of sports injuries, also contact sports have a greater injury risk than non-contact ones and in team sports more injuries occur during matches than in training, in contrast to individual sports.

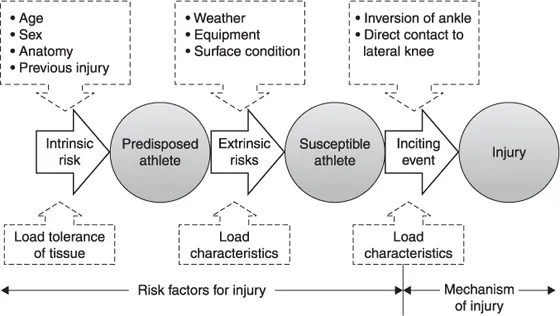

Risk factors do not infer cause, which means that having one or more risk factors does not guarantee that you will experience a particular injury. What it means is that you are statistically more likely to experience an injury as compared to a person who does not have those risk factors. The cause of injury is multifactorial involving the interrelationships between the intrinsic risks, extrinsic risks and mechanical factors present at the moment of the inciting event. There are many models that attempt to demonstrate the relationships between these factors. Perhaps the most cited is that of Meeuwisse (Meeuwisse, 1994; Meeuwisse et al., 2007). Meeuwisse describes an athlete with intrinsic risks as predisposed to injury. Furthermore, according to the model, the factors that predispose the athlete may combine with the extrinsic factors related to the sport and environment to make an athlete susceptible to injury (Figure 1.1). However, the simple presence of these risk factors is not enough to produce injury. Rather, risk factors must combine with the appropriate mechanical factors during an inciting event to produce an injury. As an example, a female basketball player may be predisposed due to her sex (intrinsic non-modifiable risk) and weak hamstring muscles (intrinsic modifiable risk). This athlete might become susceptible to injury because of environmental causes, such as the need to get around a defender quickly (extrinsic modifiable risk). She might then experience an injury while performing a cutting manoeuvre (inciting event), which places excessive load (mechanical factor) on the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), leading to disruption of the ligament fibres.

Figure 1.1 Model of relationship between risk factors for athletic injury, with examples of risk factors and inciting events and biomechanical knowledge gained (adapted from Meeuwisse, 1994).

Biomechanical perspective on injury

From a very simplified viewpoint a biomechanist uses the principles and theories of the disciplines of physics and mechanical engineering to describe the forces and force-related (mechanical) factors that lead to injury. Arguably these factors are most closely related to the study of athletic injury as most athletic injuries can be rel...