![]() Part One

Part One

1830–1880![]()

Chapter 1

Eating to live

The rural poor

Asocial history of eating out properly begins with the many rather than the few, with those for whom food was necessity rather than pleasure and who strove to obtain enough to keep them at work rather than to stimulate jaded appetites. Ironically, those whose standard of living placed them at the bottom of the social pile in the nineteenth century, agricultural labourers, were those who ate out more than any other class. Moreover, despite England’s gradual shift to an urban, industrial society, agricultural workers remained the largest occupational group in 1851 (965,000) and still in 1881 (871,000), easily outnumbering building, textile, metal or mining workers.

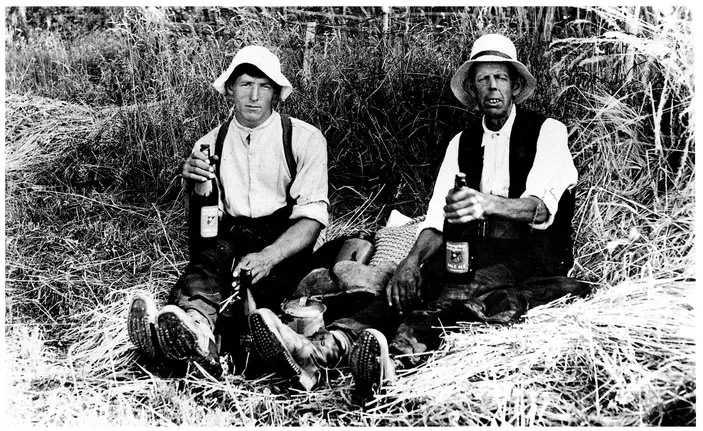

Those employed on the land necessarily ate ‘out’ in all but the most inclement weather since the various farming operations of ploughing, seeding, weeding and harvesting took them into the fields, often too far from home to return for meals. The food they took to sustain them was spread over several meal-breaks, since in summer work began at daybreak and continued until dusk – at hay and harvest-time until dark. At such busy times a first breakfast might be eaten in the fields before 6 am, a second breakfast or ‘eight o’clock’, a ‘bever’ (from the French ‘beivre’, a short break with drink) at around 10 am, the main meal or ‘nuncheon’ at midday and a second ‘bever’ in the afternoon before returning home for supper.1 The food available for all these occasions naturally depended on

FIGURE 1.1 ♦ Eating in the open. Harvesters at their 'bever' (a drink and snack, from the Old French beivre): this could be only one of four or five breaks for refreshment during a long day in the fields (late nineteenth century). Source: Rural History Centre, University of Reading.

the labourer’s earnings, the size and ages of his family, the region of the country and, ultimately, the economic position of the agricultural economy of which he was an essential part. A fair generalisation, however, is that he was the lowest paid, the worst fed and housed of all regularly-employed workers: uneducated and unenfranchised, immobilised by poverty and the Poor Laws, he had almost no power to improve his position of deferential dependence on his farmer-employer. This had not always been so. His condition had first deteriorated in the later eighteenth century when enclosures deprived many of access to land and common rights: unable to grow food, he became solely dependent on wages which failed to keep pace with the cost of living in a period of rapid inflation. By 1795 a crisis in the southern and eastern counties led to the introduction of the Speenhamland System of poor relief, which added a subsistence allowance to wages according to the price of bread and the number of dependants.2 That year in the parish of Barkham, Berkshire, bread and flour took 6/3d. out of the men’s wage of 8/- a week: no fresh meat was eaten and few families could afford more than 1 lb. of bacon, 1 oz. of tea and tiny amounts of sugar and butter.3 It has been calculated that these budgets collected by the Revd David Davies would have yielded an average of only 1990 kcals, and 49 g of protein per person per day,4 quite inadequate for a man at heavy manual work, who would need at least half as much again. The explanation must be that he consumed much more than the average for his family, with the result that his wife and children received a good deal less, a point often made by contemporary observers who noted that the man, as chief breadwinner, always took the ‘lion’s share’ of food, especially of any meat that might be available.

The distress of the labourer became, if possible, even worse during the long agricultural depression which followed the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. In 1824 wages for a married man were as little as 4/6d. a week in some southern counties, 5/0d.–8/0d. in others, but up to 12/- in Lancashire where industrial employment pushed up the general level.5 Touring the country at this time William Cobbett wrote his Rural Rides in a tone of passionate indignation. English peasants were ‘the worst-used labouring people upon the face of the earth. Dogs and hogs and horses are treated with more civility, and as for food and lodging, how gladly would the labourers change with them!’ Fortunately, there were exceptions even in the poorest areas. At Eastdean, Sussex, he encountered a young labourer sitting under a hedge at his breakfast:

He came running to me with his victuals in his hand, and I was glad to see that his food consisted of a good lump of household bread and not a very small piece of bacon. In parting with him I said, ‘You do get some bacon then?’ ‘Oh yes, Sir,’ said he, with an emphasis and a sway of the head which seemed to say, ‘We must and will have that’ . . .What sort of breakfast would this man have had in a mess of cold potatoes? Could he have worked, and worked in the wet too, with such food? Monstrous! No society ought to exist where the labourers live in a hog-like sort of way.6

Writing of his food in the 1840s, Charles Astridge of Midhurst remembered that

We mostly lived on bread, but ’twasn’t bread like we get now; ’twas that heavy and doughy ’ee could pull long strips of it out of your mouth. They called it growy bread. But ’twas fine compared with the porridge we made out of bruised beans; that made your inside feel as if ’twas on fire, an’ sort of choked ’ee.7

Potatoes would have been better than this, despite Cobbett’s hatred of them as ‘pig-food’ and ‘the lazy root’ (because they were easy to cultivate!). One of the most poignant of all accounts of eating out comes from Lincolnshire in the 1850s, where gangs of small children from the age of 5 upwards were employed in field labour: at 8 this witness was the eldest of a gang of 40 which worked for 14 hours a day in all weathers:

We were followed all day long by an old man carrying a long whip, which he did not forget to use. . . . In all the four years I worked in the fields I never worked one hour under cover of a barn, and only once did we have a meal in a house. And I shall never forget that one meal or the kind woman who gave us it. It was a most terrible day . .. the sleet and snow which came every now and then in showers seemed almost to cut us to pieces. Dinner-time came, and we were preparing to sit down under a hedge and eat our cold dinner and drink our cold tea when we saw the shepherd’s wife coming towards us, and she said to the ganger, ‘Bring these children into my house and let them eat their dinner there.’ We all sat in a ring upon the floor. She then placed in our midst a very large saucepan of hot, boiled potatoes, and bade us help ourselves. Truly, although I have attended scores of grand parties and banquets since that time, not one of them has seemed half as good to me as that meal did.8

James Caird’s enquiry into the state of English agriculture in 1850 showed that the average wage now stood at 9/6d. a week, but still 7/- or 8/- in many southern and eastern counties. He described the diet of a Dorset labourer who earned only 6/- and paid 1/- a week for his cottage:

After doing up his horses he takes breakfast, which is made of flour and a little butter and water ‘from the tea-kettle’ poured over it. He takes with him to the field a piece of bread and (if he has not a growing family, and can afford it) cheese to eat at midday. He returns home to a few potatoes and possibly a little bacon, though only those who are better-off can afford that.9

In the period of agricultural prosperity which followed between the 1850s and 1870s the poor condition of the labourer improved somewhat, though his diet remained monotonous and restricted. In 1863 he consumed on average 12¼ lb of bread weekly, 6 lb of potatoes or 27 lb per family (but up to twice as much as this where he had the privilege of an allotment), 1 lb of meat or bacon per adult and small amounts of cheese, butter, sugar or treacle: his family consumed 2½ oz of the now indispensable tea. This diet yielded 2,760 kcals and 70 g of protein per person per day, still inadequate for heavy work, for a pregnant woman or a growing adolescent.10

In packing up food for a man – and, in many cases, also a son – much depended on the wife’s skill and ingenuity in making a little go a long way and devising tasty ‘relishes’ to break the monotony of bread. In Harpenden, Hertfordshire in the 1860s, where wages were between 11/-and 13/- a week, few cottages had an oven or range, and most meals were cooked in a large pot over an open fire: whatever meat was available, flour dumplings, potatoes and greens were all boiled together, though in separate nets which allowed their cooking time to be controlled. The poorer labourers took with them for their food large ‘door-steps’ of bread, cheese, an onion and, if possible, a pint of beer, and thought it ‘A meal fit for a king ter ’ev’, but the better-off also had a dumpling with a filling of meat chopped up small (flank of beef, streaky bacon, pickled pork or liver), potato, onion and parsley, the proportion of meat usually a quarter or less. These were eaten cold or sometimes heated over a gypsy fire, or a bloater would be wrapped in several layers of newspaper and cooked in the embers.11 The dumpling was always the favourite, however, combining sustenance with portability: it fulfilled a similar role to the Cornish and West Country pasty which could provide a two-course meal in one, with meat, potato and onion at one end and apple at the other. In the Midlands and North of England local supplies of fuel allowed more home cooking, and the bread diet was varied by soups and oatmeal porridge, but the problem remained of providing suitably portable food for the field. In Staffordshire in the 1870s Tom Mullins found that little white bread was eaten:

We lived mainly on oatmeal, which was made into flat, sour cakes like gramophone records. . . . Usually enough were made at one baking to last a week or ten days. By that time they would be covered with green, furry mould, which would be scraped off.12

At last by 1880 Francis Heath was able to report ‘dawning improvement’ even in the poor western counties. Wages were still low, but now they went further with the lower prices of bread, tea, sugar and other necessities. In Somerset the labourer’s day began with breakfast of bread, bacon or dripping and fried potatoes, followed by a ‘ten o’clock’ in the field of bread, cheese and cider, dinner of bread, bacon or other cold meat and more cider, and another break for bread and cheese at four o’clock before a substantial supper at home of hot vegetables, meat or fish, bread and butter and tea, ‘making a grand total of no inconsiderable amount, and which only fairly hard work and fresh air enable him to digest’. Field fare was necessarily governed by transportability, and bread or, in the north, bannocks or oatcakes, were always the staples, but now increasingly varied with meat of some sort, often in a pastry case. Edwin Grey described the mechanics of eating out in Hertfordshire in the 1870s. The men’s food was packed up by the women overnight, and carried in a basket made of plaited rush with a flap and two handles, swung over the shoulders by a stout cord. The basket always contained some salt, for which the older men used a bullock’s horn, also a can of cold tea and a tin mug for beer. The men sat in a circle under a tree or hedge, and made their bread into a thick sandwich with whatever filling they had, then cutting pieces from the ‘thumb-bit’ with the pocket knives they all carried. In winter they made a fire to heat their cans of tea, and fashioned toasting-forks of hazel wood to cook bloaters or other foods.

I used often to find these [alfresco meals] very cheerful and amusing times, with many a laugh at the jokes bandied about; for one thing, no one apparently suffered with indigestion, so far as I could see all seemed to have excellent appetites and enjoyed their homely fare to the utmost.13

No doubt the conviviality of these occasions owed something to the ‘allowance’ of beer which many farmers gave, especially for heavy or tedious tasks. This was a long-standing custom, approved by employers as an encouragement to effort or reward for successful work, and by all labourers except the small minority who had ‘taken the pledge’ of teetotalism, and resented what was, in effect, a supplement to wages in which they did not share. The amount and strength of this perquisite varied greatly. In s...