eBook - ePub

Mass Notification and Crisis Communications

Planning, Preparedness, and Systems

- 550 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Mass communication in the midst of a crisis must be done in a targeted and timely manner to mitigate the impact and ultimately save lives. Based on sound research, real-world case studies, and the author's own experiences, Mass Notification and Crisis Communications: Planning, Preparedness, and Systems helps emergency planning professionals create

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mass Notification and Crisis Communications by Denise C. Walker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Gestione. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

History of Communications

The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.

George Bernard Shaw

HISTORY OF COMMUNICATIONS

The history of communications began with the start of life, and it has been a part of our lives ever since. Communication means information that is shared by two or more people. Communications includes a sender and a receiver. The sender is the one that triggers the message. The receiver is the party who receives the message.

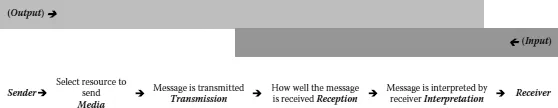

For communications to occur between a sender and receiver, you first need media to send the message (the output) from the sender. Media is the resource used for send a message, such as paper, television, telephone, or smoke signals. Once the sender has selected a media, the sender will transmit the message. Transmission is the method used for sending a message, such as over the radio or cellular phones, by airwaves, or using a physical transporter such as a homing pigeon or postal service. The media and transmission used by the sender will determine how well the message is received, called reception. Is the radio transmission clear enough to be intelligible or is the handwriting legible? As the message is received, it is interpreted by the receiver and becomes the input. Interpretation by the receiver is the most critical component in the formation of a common understanding between the sender and the receiver. Interpretation determines how well the receiver understands what has been sent (see Figure 1.1 Communications process).

Does the sender write the message in English not knowing whether the receiver can read, write, speak, or understand English? Must the receiver hear the message in order to interpret its meaning even though the sender is unsure whether the receiver is hearing-impaired or otherwise unable to interpret the message? To have a common understanding between the sender and receiver the media, transmission, reception, and interpretation considerations play a pivotal role in communications.

FIGURE 1.1 Communications process.

COMMUNICATIONS—3500 BC TO 1 BC

There are records dating back to 3500 BC showing a time when paintings were made by indigenous tribes as a means to communicate. Around that period, the Sumerians developed pictographs of events that were written on clay tablets. The Egyptians also created hieroglyphic writing (see Figure 1.2 Early Egyptian hieroglyphic alphabet). In 1500 BC, the Phoenicians created an alphabet. In 1400 BC, bones were used for writing in China, the oldest record of writing. In 1300 BC, drum beat codes sounded alarms during the Shang Dynasty in China. The Chinese government introduced the first postal service in 900 BC. The postal service was one of the first processes used to deliver communications over a distance to a specific individual.

In 776 BC, homing pigeons were used to send messages including an announcement of the winner of the Olympic Games to the Athenians. Before homing pigeons, human messengers running on foot or horseback were the only way to send messages from town to town or to relay orders and intelligence during wartime. This was a dangerous task for human messengers. Messengers were killed, bribed, or their messages intercepted. About 400 years later, more effective communication methods were introduced.

FIGURE 1.2 Early Egyptian hieroglyphic alphabet.

Between 1200 BC and 100 BC, fire messages were used from relay station to station instead of human messengers in Egypt and China. In ancient Greece, the Greek were reported to have used fire signals to send a message from Troy to the city of Argos (chief town in eastern Peloponnese), about 325 miles (600 km) in the late eleventh century BC. Troy was located on the top of the Hisarlik, a mountain in western Anatolia, the area now known as Turkey. It was said that alone on the Argos palace roof, the watchman awaited the fire signal that would tell the household that the Greeks had captured Troy. The message reached the city of Argos after a few hours.1 Smoke signals were also used by Native American tribes.

HELIOGRAPHS

Sending messages using mirrors or shiny metals and the rays from the sun has been done by flashing reflected rays to another location up to 50 miles away. This form of communicating is known as heliography, with the first recorded use in 405 BC. The ancient Greeks used their polished shields to signal in battle. The Roman emperor Tiberius was thought to have sent coded orders using heliographs daily to the mainland, about 8 miles (12.8 km) away in 37 AD. The Egyptians were also known to have use heliographs that could be seen as far as 80 miles away.2

Thousands of years later, heliographs remain in use. As late as 1979, Afghan forces were reported to use heliographs to warn of approaching enemy troops during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Today, heliographs are included in some survival kits used by hikers and pilots for emergency signaling and for the search and rescue of aircraft. An emergency is a situation or event that presents an immediate risk to life, health, property, or the environment. Heliographs are also used to measure long distances by triangulations by the U.S. Coast Guard and for geological surveys in the early 1900s.3

Other primitive forms of communications used for telegraphy over distances include smoke signals, torch signaling, and signal flags. The word telegraph, with its origins from the union of Greek words tele and graph, that essentially mean “long-distance writing.”

PAPER, NEWSPAPERS, AND MAGAZINES

The Chinese were the first to use paper in 104 AD. In 1450, when paper was easily produced and widely available, newspapers were created in Europe. In Renaissance Europe, newsletters were handwritten and privately circulated among merchants. They disclosed information about wars, economic conditions, social customs and “human interest” features. Printed news pamphlets, also known as broadsides, were the forerunners of the newspaper. German broadsides of the late 1400s had highly sensationalized content.

Newspaper circulations have grown over the years. The United States had nearly 2,150 daily newspapers in circulation in 1900 and peaked at 2,200 by 1910. Daily newspapers were a way to share information on events in the coverage area and world news. By 1967, most newspaper and magazine production was digitized (Media History Project). In 1910, there were an estimated 1,800 magazines in publications. A magazine is a publication published periodically, less frequently than newspapers.

TELEGRAPH SERVICE AND MORSE CODE

Telegraph Service

A Frenchman named Claude Chappe invented the first long-distance semaphone telegraph line in 1793. Telegraph services was used during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars when communication systems were simplistic, relying mainly on mounted dispatch riders. As telegraph service was adopted, communication towers were erected in the line of sight of each other. Once the towers were installed, the French sent a signal using the telegraph system from Paris to Lille, approximately 118 miles (191 km) in five minutes. Each tower had 196 combinations, also known as signs, and each was worked by a series of pulleys and levers. An operator could send three signs in a minute, provided visibility was good.

There were a number of significant communication “firsts” during the eighteenth century. Many of these can be attributed to the military needs of the time. Major wars include the French Revolution starting in 1789, the Napoleonic Wars that began in 1803, the Mexican–American War of 1846, and the U.S. Civil War in 1861. The first optical telegraph system was invented in the mid-1800s that covered approximately 3,100 miles (5,000 km) and encompassed more than 550 stations. These early systems included the naval semaphore system, the railroad semaphore system, and the “wig-wag” system.

William Cooke and Charles Wheatstone developed an early form of telegraphy system called the English Needle Telegraph in 1837. This system used pointing needles rotating over an alphabetical chart to indicate the letters that had been sent. The major drawbacks of this system were that it had a complex configuration and it was slow. These were common issues among electrical telegraphing systems of this era.

Optical and visual telegraphy systems enabled information to be transmitted more quickly than the fastest form of transportation. This is at a time when advances in communications had outpaced earlier messenger systems. Telegraphy systems enabled the use of error control (resending lost characters), message priority, and the flow control (send faster or slower) for the first time. These were significant milestones in communications. These concepts remain in use today for crisis and emergency communications. Telegraphy systems continued to evolve with encoded shutter system developments in Sweden and England in the late 1800s.

Morse Code

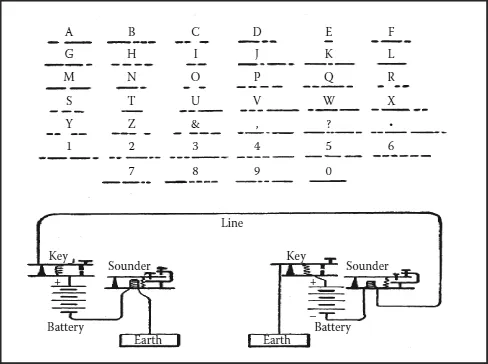

Samuel Finley Breese Morse invented the Morse code in 1835, a landmark in using technology to communicate electronically. Morse code is a method for transmitting textual information using a series of indentation marks (dots and dashes) on paper tape that can be directly understood by a skilled listener or observer without special equipment (see Figure 1.3 Morse code).4 The system sent pulses of electric current along wires that were controlled by the receiving end of the telegraph system to deflect an electromagnet.

FIGURE 1.3 Morse code.

Samuel Morse entered into an agreement with Alfred Vail to expand the original code to include the alphabet, numbers, and special characters for broader appeal. A group of “dots” also known as dit (·) or short marks and “dashes,” also known as dah (-) or longer marks are assigned to a character. Pauses, referred to as gaps, are used between letters, words, and sentences. A short gap is used between letters, a medium gap is used between words, and a long gap is used between sentences.

Eight years later, in 1843, Samuel Morse invented the first long-distance electric telegraph line. The first telegraph message was sent electrically from the U.S. Supreme Court chamber in Washington, DC, to the railway depot in Baltimore, Maryland. Congress funded construction of this experimental telegraph line. The U.S. Morse code was sometimes known as the “Railroad Morse.” A trained operator could now send or receive 40–50 words per minute. By 1914, automated transmission was in use. A trained operator could handle more than twice the original rate.

The modern International Morse code invented by Friedrich Gerke was introduced in 1848. Morse code gained popularity in Europe while the United States continued to use the former version. The International Morse code eliminated the use of spaced dots. This system had an advantage over other forms of communications during this time because it had an easy working principle, and it could function efficiently with low-quality wires common in rural areas. As the number of users and undersea cables increased, transmission errors occurred.

Morse code with its many improvements became a mainstay in communications during disasters and emergencies for more than 160 years. A disaster is a natural situation or event that overwhelms the local capacity to respond, recover, prevent, or mitigate damage and may require a request for external help. Morse code was the backbone of early emergency communications technology.

MAIL AND PARCELS

The Chinese introduced the first postal service in 900 BC. The Pony Express was used for U.S. mail delivery during the Wild West days; by 1912, the first mail was carried by airplane.

Toronto, Canada, first used numbered postal zones in 1925. By the 1940s other Canadian cities were using the system. For example, the postal zone used for Toronto was 5. Mail would be addressed giving the postal zone name and postal zone number, and province, that is, Toronto 5, Ontario. By 1943, the City of Toronto was divided into 14 zones using the numbers 1 through 6, 8 through 10, and 12 through 15. The numbers 7 and 11 were not used and a 2B zone was added. Today the postal code contains six alphanumeric characters in the form of A#A #A#. The letter “A” represents an alphabetic character and the # represents a numeric character. The postal code consists of two three-character segments. The first section is for the forward sortation area A#A, and the second section is for the local delivery unit #A#. Similar systems were implemented elsewhere around the world over the next 20 years.5

In 1943, the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) started using postal zones for large U.S. metropolitan areas. In 1963, 20 years later, the USPS introduced ZIP codes to leverage technology in managing the explosive growth of mail. ZIP is the acronym for Zoning Improvement Plan. The use of ZIP codes was optional until 1967 when USPS required all second-class and third-class mail to be presorted by ZIP code. In 1983, the ZIP+4 system, also called the “plus-four codes” or “add-on codes,” was implemented by USPS. The additional four digits represent a geographic area within a ZIP code delivery area, such as an apartment complex, neighborhood, or other small community. A postal bar code is now used for automated sorting of mail called the Postnet. There are long Postnet bar that contain the ZIP+4 code and the short-Postnet bar that contains only the five-digit ZIP code.

In addition to ZIP codes, globally ISO2 ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1 History of Communications

- Chapter 2 Disaster Communications—Two-Way Conversations

- Chapter 3 Dynamics of Communications and Concepts of Operations

- Chapter 4 Challenges to Effective Communications

- Chapter 5 Changing Realities in Emergency Communications

- Chapter 6 Emergency Communications Framework

- Chapter 7 A Crisis Occurs … Now What?

- Chapter 8 International, Federal, State, and Local Laws, Regulations, Systems, Plans, and Structures

- Chapter 9 Ripple Effect of Social Media and Social Networking

- Chapter 10 Solutions—Some Solutions Are Better than None

- Chapter 11 Learning Your Systems Requirements

- Chapter 12 Picking a Solution That Fits

- Chapter 13 Effective Communication Plans

- Chapter 14 Getting the Message Right the First Time

- Chapter 15 Prepare to Prosper

- Chapter 16 Conclusions

- Appendix A: List of Acronyms

- Appendix B: Sample Mass Notification System Activation and Criteria Guidance Sheet

- Appendix C: Sample Messages

- Appendix D: List of Questions to Ask a Vendor before You Buy

- Appendix E: Sample Social Media Strategy

- Appendix F: Emergency Call Numbers

- Glossary

- Additional Resources

- Index