eBook - ePub

Managing Country Risk

A Practitioner’s Guide to Effective Cross-Border Risk Analysis

- 308 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

What would you do if a law that enabled your investment to operate successfully abroad suddenly changed, and your business could no longer operate profitably there? Imagine exporting goods to a government buyer only to discover after the fact that your home country, or the United Nations, has just imposed an embargo on that country. Managing Countr

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Country Risk in Perspective

When you consider what a mystery the East Side of New York is to the West Side, the business of arranging the world to the satisfaction of the people in it may be seen in something like its true proportions.

Walter Lippmann, 19151

Introduction

It became fashionable for political and economic pundits to declare in 2011 that as a result of the arrival of the Arab Spring, the world had become a more dangerous place, and that the risks associated with conducting cross-border business had risen. One could perhaps legitimately make such an argument in the countries directly affected by the Spring, but was cross-border risk in 2011 really more generally perilous than it was in, say, 1988 or 2001, when global shock waves resulted from the collapse of the Soviet Union and the beginning of the War on Terror? Not in my view—yet the chorus of analysts’ voices made it sound as if the Arab Spring had an equally profound impact on global trade and investment.

If, as noted by Lippmann, the world was considered mysterious in 1915, the Arab Spring was indicative of how political change in the second decade of the twenty-first century could be characterized as evolutionary and in a seemingly constant state of metamorphosis. It is no longer so easy to define one’s allegiance or to identify with a single country or strain of political thought. Globalization, interconnectedness, social media, and the age of instant communication have greatly changed the political and economic landscape, as well as the nature of structural change in countries throughout the world.

In 1988 and even as recently as 2001, trade and investment decisions were by definition based on less available information and less sophisticated means of assessing and managing risk. Today, cross-border traders and investors benefit from a more level playing field with respect to access to information, more open markets, and a more competitive landscape. More countries want to attract foreign direct investment (FDI), enhance international trade, and be members of the global “club” than ever before. To do so, they must maintain a competitive footing and constantly reinforce their comparative attractiveness as trade and investment destinations. That makes the global trade and investment climate less risky than in recent history, but it also makes the need to understand the true nature of cross-border risk more acute than ever before.

Insight into the Foundation of the Arab Spring2

Understanding why the Arab Spring erupted is important not only because so many dynamics were at play, but also because no one accurately predicted how or when such upheaval would occur, and its impact was dramatic. Businesses have naturally become more risk averse as a result of the changes that have taken place throughout the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) since Muhammad Bouazizi, a food cart vendor, lit himself on fire in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia, in January 2011. He did so out of utter frustration and hopelessness, and his story resonated throughout the country and region. But the aspirations of the region’s people as manifest by what came to be known as the Arab Spring must be considered in the context of an underlying unease about the scope and impact of political and economic change. While the region’s businesses quickly adapted to the many changes that resulted from the onset of the Arab Spring, many of them also came to recognize that the likely result would be an extended period of uncertainty and some degree of doubt about whether all the change would in the end result in meaningful long-term benefits.

Let us examine why the Tunisian spark ignited a wildfire that spread throughout the Middle East, as it will provide insight into how politics are inextricably linked with economics and how some political change that is decades in the making can occur in an instant. A corollary to one of the best known theories of human development—basic needs theory—is that as long as governments deliver the basic services their citizens require, there is little inherent incentive for them to rise up in opposition. Even if there were an incentive for them to do so, it is reasonable to ask whether they are willing to risk what they have for the hope of achieving something better in the long term.

It can certainly be argued that citizenries that have only known one-party or one-person rule, as is so common in MENA, will be hesitant to embrace change. Even if they were given an opportunity to participate in a genuinely democratic vote, the fact that it would be for the first time in many countries in MENA raises doubt about whether voters would truly vote their consciences. As the recent democratic experiment in Iraq has demonstrated, the process can be highly politicized, and remnants of long-established political forces can clash with new political forces for many years before the dust settles and the benefits of change become apparent. Political change implies uncertainty and the average person is less likely to risk stability for an uncertain future.

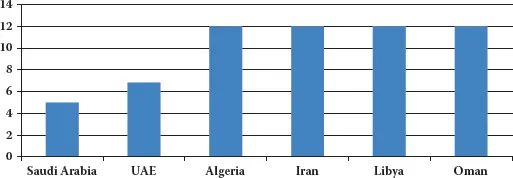

The Middle East’s remaining governments have considered what they must do to prolong their time in power. Their ability to be perceived to be providing meaningful basic services may in large part determine how long they can remain in power; this was certainly the case with Saudi Arabia in the months following Ben Ali’s overthrow in Tunisia. Given that oil production costs in the region are generally below $15 per barrel, hefty short- and medium-term revenues gave the governments of oil-producing nations options they may not otherwise have had to help ensure that basic needs were met (see Figure 1).

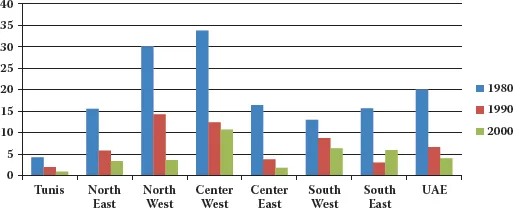

If the Tunisian example is any guide, they have a lot of work to do. Ben Ali was ultimately driven out of power by a chain of events originating in Sidi Bouzid, in the country’s western center. According to the World Bank, this part of Tunisia consistently had the highest rate of poverty in the country between 1980 and 2000—more than twice the national average in 2000. The people in Sidi Bouzid had little to lose by promoting political change once an opportunity was created. But the reason that the suicide of food cart vendor Muhammad Bouazizi triggered the riots and Ben Ali’s subsequent departure is that opposition groups, trade unions, and much wealthier parts of the country became galvanized: They were collectively tired of being oppressed, too many of them were unemployed, and Ben Ali’s family had enriched itself too grotesquely for too long.

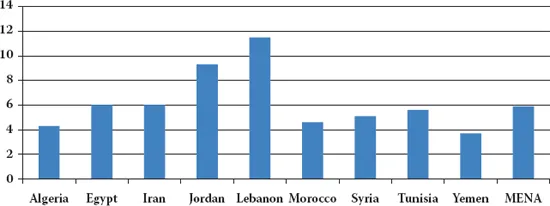

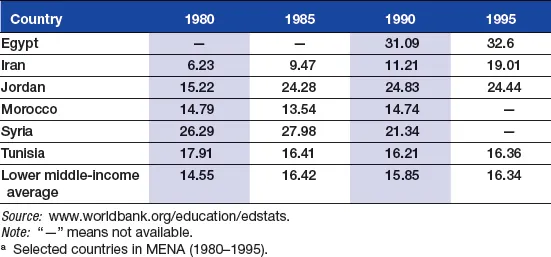

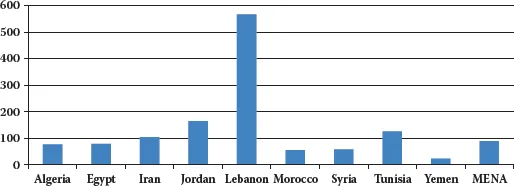

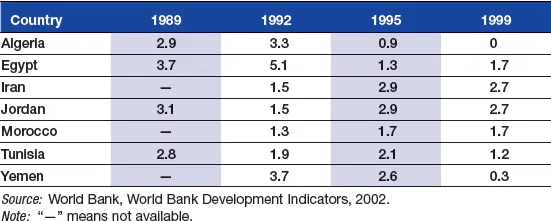

Tunisia had been neither the worst nor the best at providing basic services to its people. As noted in the charts that follow, the country was either at or above average for lower middle-income countries in the region with respect to total spending on education between 1980 and 1995. But its spending on education actually declined or remained stagnant during the 1980s and 1990s. Tunisia was again an average performer in terms of health expenditures as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP) and one of the better regional performers in terms of health expenditures per capita. The Tunisian government provided free or subsidized health care to its lowest income groups, but the percentage of GDP the government devoted to food subsidies declined by more than half between 1989 and 1999, in the first decade of Ben Ali’s reign (see Figures 2 and 3 and Table 1).

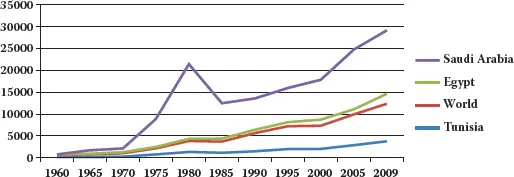

So, Tunisia had done neither particularly well nor particularly badly in looking after the basic needs of its people in recent history. Tunisia’s GDP per capita has risen notably over the past 50 years, reaching US$3,800 by 2009—at the top of the World Bank’s classification for lower middle-income countries, albeit well below the global average. That the country is well integrated with Europe both from a business and tourism perspective has meant that the financial crisis hit Tunisia harder than other, less well integrated countries in the region. This undoubtedly raised the level of common dissatisfaction with the Ben Ali regime (see Figures 4 and 5 and Table 2).

Had the Tunisian masses been given greater freedoms and had the state not held such a vise-like grip on power, the spark that occurred in Sidi Bouzid may not have turned into a bonfire. Tunisia under Ben Ali had been a police state virtually since he assumed power in 1987; its security apparatus came to be larger than that of France, which has six times its population. With unacceptably high unemployment rates throughout the Middle East and millions of young people yearning for a greater voice, the potential for a similar backlash certainly exists in a variety of other countries, such as Algeria and Saudi Arabia.

FIGURE 1 Estimated break-even oil production costs for selected MENA countries (US$). (From: http://www.reuters.com/article/2009/07/28/oil-cost-factbox-idUSLS12407420090728)

FIGURE 2 Percentage of population living in poverty in Tunisia by region (1980, 1990, and 2000). (From: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPGI/Resources/342674-1115051237044/oppgtunisia11.pdf)

FIGURE 3 Health expenditures in 2002 as a percentage of GDP. (From World Bank, World Development Indicators, 2003.)

TABLE 1 Percentage of Total Government Spending on Educationa

While many of the region’s governments made a more visible effort to appeal to the common citizen through enhanced public services, food and gas subsidies, and more funding for education, none of them released their own vise-like grips on power. They attempted to walk a fine line between enhanced reforms and an enhanced security apparatus, or they simply restricted freedoms even further. What would have been much smarter is for these governments to release their grip on power gradually while making genuine overtures to demonstrate that they were open to changing their tune. If the masses saw the door open a crack, their temptation to force it open may have been reduced. But the fact that this did not happen implies that entrenched governments throughout the world may be inclined to remain in power at any cost, which certainly has important implications for companies considering trading, investing, and lending abroad, as well as for the analysts trying to determine the true nature of the risks involved in doing so.

When the process of political change began in MENA in January 2011, there was much hope among its people and concern among its governments about the manner in which this change would evolve. For most of its people, there was tremendous hope that the decades of enduring repression under authoritarian governments would soon come to an end. For many of its governments, there was hope that the introduction of incremental reform would placate public sentiment and enable continuation of the status quo. The aspirations of neither have come true.

While citizens in Egypt and Tunisia had initial cause for celebration when Presidents Ben Ali and Mubarak were forced to abdicate their presidencies, it quickly became clear that their jubilation was premature. While the figurehead of the only government many of them had ever known was indeed removed, the infrastructure of the government and virtually all of its other members remained in place.

FIGURE 4 Health expenditures in 2002 per capita (USD). (From World Bank, World Development Indicators, 2003.)

FIGURE 5 Tunisia versus selected countries and the world: GDP per capita at current prices (not adjusted for inflation; converted to USD at market exchange rates). (From World Bank, World Development Indicators, 2010.)

TABLE 2 Food Subsidies as a Percent of GDP (1989–1999)

Historic Change, But Not “Revolutionary”

The reason why the political upheaval in MENA was historic is precisely because it involved establishing a new kind of relationship between governments and the people they govern: a fundamental overhaul of Arab state/society relations that have remained relatively unchanged for more than half a century. According to a study by Freedom House3, in 67 countries where dictatorships have fallen since 1972, non-violent civic resistance was a strong influence more than 70% of the time. Change was made through civil society organizations that utilized non-violent action or other forms of civil resistance. It would be nice to believe that Egyptians, Libyans, and Tunisians have reasonable grounds to hope that the fruit of their labor will ultimately be democratically elected and functioning governments, yet the average citizen in these countries is unlikely to find that the governments they thought would replace the ancien regimes will be everything they had hoped for.

There will inevitably be immense pressure on whatever form of government ultimately succeeds the current regimes in all these countries. They must be seen to be bringing about meaningful change quickly, but this will be far more difficult to achieve than would ordinarily be the case and is likely to result in one of two scenarios. The first is that, frustrated b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- List of Maps

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- The Author

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1 - Country Risk in Perspective

- Chapter 2 - Foundations of Country Risk Management

- Chapter 3 - Assessing Country Risk

- Chapter 4 - Country Risk Assessment in Practice

- Chapter 5 - Political Risk Insurance

- Chapter 6 - Tales from the Battle Zone

- Chapter 7 - The Importance of Understanding China and Its Place in the World

- Chapter 8 - Shifting Pendulums, Pressing Concerns, and the State of the World

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Managing Country Risk by Daniel Wagner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Finanzas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.