- 80 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Lewis Wickes Hines documentary photography helped promote the cause of the National Child Labor Committee, which published there declaration in 1913. This text is a collection of photographs showing children at work from 1910 to 1935 as Hines travelled across America.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Lewis Hine by Richard Worth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Great Social Peril

The great social peril is darkness and ignorance.

–Lewis Hine

In 1910, a shy, slim photographer stood in front of a large audience which sat in hushed silence. They were stunned by the images that he had just shown them. The photographer had used a magic lantern—the forerunner of the slide projector—to project photographs that had been reproduced on glass plates onto a screen. Shocking images of children—Americas children—engaged in backbreaking labor filled the darkened room. Over 2 million children under the age of sixteen worked twelve to fourteen hours a day in similar conditions.

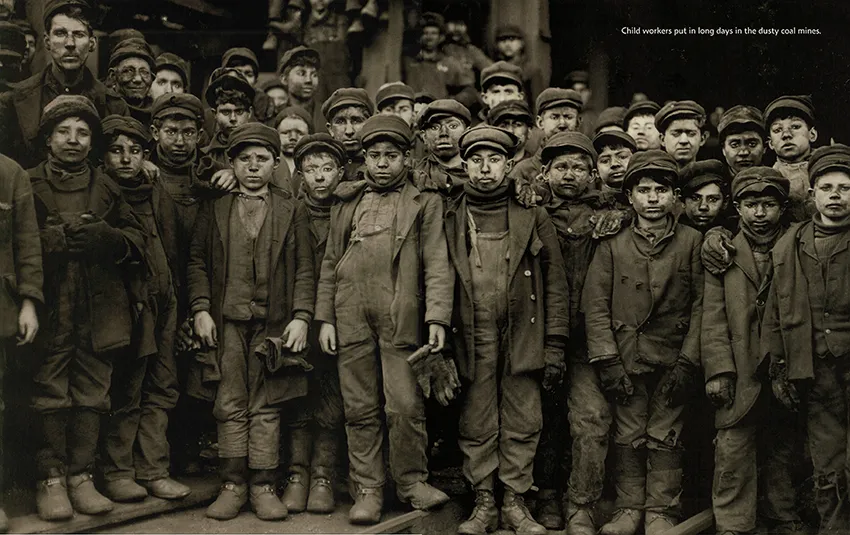

One of these children was a little girl named Sadie, who stood in front of a giant spinning machine, working in a mill where the heat and the dust made breathing very difficult. Others were boys who worked deep inside the Pennsylvania coal mines as trappers, opening the doors from the mines to let out the cars filled with coal. Day after day, they breathed in black coal dust, which coated their lungs and their faces with soot.

Some younger children were breaker boys, sitting outside the mines over coal chutes and taking out pieces of stone that could not be sold because they would not burn. Their fingers were constantly cut by the coal flowing down the shoot. “While I was there,” the photographer said, “two breaker boys fell or were carried into the coal chute, where they were smothered to death.”

Some children worked in the tenement buildings of large cities, such as New York and Chicago. There, entire families worked together in poorly lit apartments with no fresh air, making artificial flowers or sewing lace. They earned about $ 1 a day, six days a week, often working until late in the evening. The lace or the flowers they made were sold to affluent people, such as the ones who sat in the audience listening to the photographer’s lecture and looking at his pictures. They seemed to have little or no idea of the working conditions that they saw on the screen.

“The great social peril is darkness and ignorance,” the photographer wrote. His goal was to educate his audience and increase their understanding of children’s working conditions. Mostly, he let the subjects speak for themselves as they looked directly into his camera and communicated their stories. But these were not sad victims. They were proud children whose voices were heard through the pictures and descriptions provided by the soft-spoken photographer.

Immigrant families made lace in their dreary tenement apartments for $1 a day.

The United States was in the midst of an industrial revolution, which had begun during the nineteenth century. Factories had sprung up across the country. Deep mines had been dug to provide large supplies of coal that could fuel the new manufacturing plants, and cities had grown to house the hundreds of thousands of workers needed for America’s industries. While some entrepreneurs became rich during industrialization, many other people worked for low wages and long hours in the mines, the factories, or in their own homes. Adults and children worked side by side to earn enough to feed their families. There were no laws protecting the health and safety of workers and no laws preventing child labor.

Hine photographed young mill workers who used their meager pay to help support their families.

As his audience soon realized, the young photographer who stood before them possessed a genius for capturing these working people with his camera. But his photographs also were designed to persuade his viewers that any society that allowed young children to work under such terrible conditions must be changed. Through this powerful presentation and other pictures that he had produced, the photographer created the first American photo stories—a visual documentary aimed at bringing social reform and changing the lives of child workers. He called it “social photography.”

The photographer’s name was Lewis Wiekes Hine.

Two-year-old Lewis Hine stands next to the drum his father carried as a young drummer boy during the American Civil War.

CHAPTER TWO

Becoming a Photographer

The highest aim of the artist is to have something to relate and to know how to select the right things to reproduce that story.

–Lewis Hine

Lewis Wiekes Hine grew up in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Settled in the mid-1800s, Oshkosh had become a prosperous center of the lumber and furniture industries. In the center of town, Douglas Hull Hine and his wife, Sarah, ran a busy restaurant. Before coming to Oshkosh, Sarah had been a schoolteacher, and Douglas had served as a drummer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. They had three children, two daughters and a son. Lewis, the youngest, was born in 1874.

As he grew up, Lewis watched his parents work long hours to make their business a success. Then, his stable family life suddenly came to an end in 1892, when his father was accidentally killed. Lewis finished high school and immediately went to work at a local furniture factory, earning $4 for a six-day, eighty-hour workweek. It was not much money, but Lewis’s income helped support his mother.

When a depression hit America in 1893 and the furniture company went bankrupt, Lewis Hine was forced to look for other work. He drifted through a series of jobs, working as a delivery boy, a salesman, and a janitor at a bank, where he was eventually promoted to the position of secretary to the bank’s head cashier. “I was neither physically nor temperamentally fitted for any of these jobs,” Hine wrote later.

Along the way, Hine met Professor Frank Manny, who taught at the Oshkosh State Normal School, a teachers’ college. Manny became his mentor and persuaded Hine to take classes at the teachers’ college. Hine also studied drawing and sculpture and attended the University of Chicago, where he took education courses.

In 1901, Manny left Oshkosh to become superintendent of the Ethical Culture School in New York City. The school’s curriculum combined high school academic courses with vocational training. Many of the students were the children of immigrants, millions of whom were coming to the United States from Europe. The largest number of immigrants came to New York City, where they found homes and jobs in the city’s densely packed neighborhoods. Most of these immigrants came from Central Europe, and they spoke little or no English. At the Ethical Culture School, immigrant children learned English, mathematics, and the other skills necessary for them to find work after graduation.

Hine grew up in the town of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, shown here in about 1850, in a painting by Louis Kurz.

Manny invited several teachers from the Oshkosh State Normal School to accompany him to New York. He also invited Lewis Hine. Hine became a teacher of geography and nature studies, and almost immediately he demonstrated his skills as a gifted teacher. Hine was a wonderful actor and entertained his students while he taught them. In 1904, he briefly returned to Oshkosh, where he married Sara Rich, a woman whom he had met at the Normal School.

Meanwhile, Hine was attending New York University, where he earned a master’s degree in education in 1905. During his early years at the Ethical Culture School, Hine also began experimenting with a camera. Frank Manny was looking for someone to record school events, and Hine’s expertise—although it was, at first, very limited—fit perfectly into Manny’s plans.

“I had long wanted to use the camera for records and you were the only one who seemed to see what I was after,” Manny later wrote to Hine. “You were adequate, ready to learn and used not only me but everyone in sight who was willing to help.” Hine read how-to magazines, which contained instructions on photography. He also learned how to develop photographs using chemicals in a darkroom. At this time, photography was little more than a half century old in the United States. Pioneering work in the field had been done by men such as Mathew Brady. Brady had created photographic portraits of political leaders such as President Abraham Lincoln, as well as vivid battle scenes of the American Civil War.

Hine began photographing school events, which included dances and club meetings, as well as students working in the school carpentry shop and taking instruction in an art class. He also started teaching his students how to operate a camera. The program was partly designed as vocational training. It taught students how to become photographers, providing them with a possible occupation after they graduated from school. But even more important, Hine believed that by using a camera, his students would learn how to see the world around them and interpret it for others. They photographed the ships in New York Harbor, proud symbols of American commerce, as well as the natural world of trees and flowers, which Hine loved very much. Most of the students had never been outside New York City before, so the world of nature offered a new experience for them.

HINE ON PHOTOGRAPHY

About his early experiences as a photographer, Hine wrote, "A good photograph is not a mere reproduction of an object or group of objectsit is an interpretation of Nature, a reproduction of impressions made upon the photographer which he desires to repeat to others." He added, "The highest aim of the artist is to have something to relate and to know how to select the right things to reproduce that story." As these words indicate...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Declaration of Independence

- Map

- CHAPTER ONE The Great Social Peril

- CHAPTER TWO Becoming a Photographer

- CHAPTER THREE Hine at Ellis Island

- CHAPTER FOUR The Tragedy of Child Labor

- CHAPTER FIVE Hine and World War I

- CHAPTER SIX Men at Work

- CHAPTER SEVEN The Great Depression

- Glossary

- Time Line

- Further Research

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author