You have just taken up a job in a museum as project manager leading a team with responsibility for the digitisation of a collection of some 300,000 natural science objects preserved in a variety of ways. Your director is expecting results on schedule and within budget, making the collection accessible to a wide range of users. Or perhaps your background lies elsewhere in the museum sector and this natural science collection is part of a broader collection for which you have responsibility. Or, maybe you have spent some years as a researcher using the collections and now in your new management position find yourself responsible for their preservation and access to users. Whichever of these or many more scenarios fit your personal circumstances you will be confronted with a baffling array of questions.

Where do you start? There may be help from colleagues or there may not and perhaps you are the only natural scientist in the institution. You know that you need to take a strategic approach and not be drawn into detail – that can come later or be the job of your team if you have one. These are the positions that we, the authors, were once placed in. We all agree that we would have loved it if there had been a book that would have helped us to ask the right questions and encouraged dialogue with colleagues to make real changes. We hope that this is that book and that we can share our experiences and some of the methodologies and tools that we have developed and used during our careers. Many of the challenges we experienced were related to the nature of natural science collections themselves, their vast size and the way in which they are used. Other challenges were with the individuals with a wide range of skills, knowledge and world views that we were now to manage. Museum workers from other disciplines are often amazed if not shocked by the tens of thousands of specimens that are traveling around the world in the mail as loans from museums to researchers and back. Natural science collections do share many characteristics with other museum collections and are a popular element for museum display and education as are art and humanities objects. However, those on display are a small fraction of the vast resource held in storerooms around the world. In this book we will focus on natural science, but we hope that many of the questions we pose and answer will be applicable elsewhere.

What is special about natural science collections?

While natural science collections share many characteristics with other museum collections, they have a particular combination of characteristics that present unique challenges to their preservation and opportunities for their use. They tend to be high in numbers (for example the largest collection is that of the Smithsonian National Natural History Museum with 146 million specimens); they are composed of natural material rather than human manufactured objects; they are highly diverse in both material and size; most were created as a research infrastructure (curiosity and research driven) supporting and linked to active research; they are mostly made up of unique individuals so for example, like human beings, none of the millions of beetles in a particular collection is a copy of another one; their labels hold data that provides a record of the existence of an organism in space and time. Some have special status as type specimens, the anchor point for scientific descriptions and names.

The changing landscape

The acquisition, care and management of natural science collections have always been challenging. From the activity of collecting specimens in extreme environments or from distant and unfamiliar countries, to satisfying the exacting preservation requirements of specimens that would otherwise naturally deteriorate, collections management has always required specific knowledge and skills.

The landscape of increasing demands for virtual and physical access, technical opportunities and challenges, as well as constrained resources, drives collections professionals to continually adjust and tune their approaches.

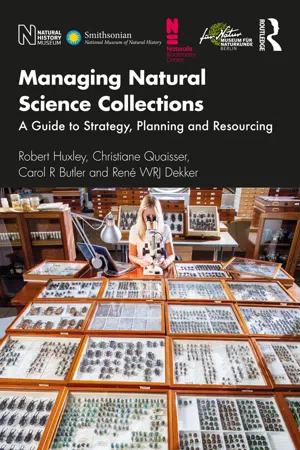

Collections of dried plants, pinned insects, fluid-preserved invertebrates, stuffed vertebrates, fossils, minerals, rocks and maybe even ice cores, described as natural science collections, are housed and mostly cared for in a variety of institutions around the world from the large purpose-built natural history museums, through herbaria of botanic gardens, to university collections and local, often multidisciplinary museums. These natural science collections stimulate curiosity and wonder, leading to scholarly enquiry and discovery as well as learning and enjoyment through exhibition and education programmes for all ages.

In the last 25 years, natural science collections have increasingly been viewed collectively as a vast distributed infrastructure for research and discovery, contributing to our understanding of the diversity of life and providing a source of baseline data for research from human and animal health to environmental and climate change. This change in perception mainly reflects a shift of research focus to more applied science with societal relevance. New scientific questions arise, driven by the transformation of physical entities to digital surrogates from multiple source collections across the world which can be integrated, repurposed and presented through joint web portals.

Challenges of natural science collections

Natural science collections number in the tens of thousands to millions in institutions around the world. The availability of funds to care for, house and make them accessible to the expanding user base has diminished significantly, putting many, especially smaller collections, at risk of loss or dispersal. Their scale and changing usage present new challenges to those responsible for their care, development and accessibility. There is a greater need for collaboration, common approaches and joining forces, and consequently there is a need for greater understanding of strategic management and an understanding of their changing position in science and society. At the same time, individual specialist curators with in-depth knowledge of the natural world have become an increasing rarity. Although the same trends can be seen in arts and humanities collections, natural science collections have many specialist qualities and needs. This presents different challenges to managers of these collections, whether they are familiar with natural sciences or are from other academic backgrounds.

The scope of this book

In this book we aim to share our experiences developing as managers in four large natural science museums and also some of the products of the various international collaborative projects that we have worked on over the last 20 years. We have had close involvement with specialist societies such as the Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections (SPNHC), and through collaborative projects we have led and participated in surveys and reviews of museums large and small in many countries. This experience has led us to believe that the principles described in this book can be applied at all levels, from the largest nationals to small local museums with a single staff member and a team of volunteers, or to specific collections projects such as large scale digitisation or a major rehousing. We hope that it will assist you in making strategic decisions regarding care, development and access and indirectly to encourage a consistent approach to managing natural science collections to ensure their present and future availability and relevance. Regardless of your personal position and the governance and mission of your institution, it aims to help you to gain confidence, build experience, and, importantly, to know what questions you need to ask when confronted with drawers of insects, cabinets of plants and boxes of fossils of varying states of preservation.

Principles of good practice and resource optimisation in an ethical and legal context are considered throughout the book, using case studies, sample documents and templates, all of which can be used for discussion and teaching, and links to references. We aim to pose questions and give answers from our perspective but at the end of the day, how you will answer them will depend on your own circumstances, vision and objectives.

Although we will direct you to specific references and general reading, much of what we share with you below is based on our many years of experience and knowledge as scientists and museum professionals. Many terms, acronyms and concepts are included in the Glossary.

We do not aim to cover operational aspects of managing natural science collections as there is a wealth of literature available and excellent resources developed through specialist societies. Topics that apply across the museum sector, such as documentation, are expertly dealt with by the Spectrum standard for example (https://collectionstrust.org.uk/spectrum/). Preventative conservation (which ultimately underpins all the processes we describe) has in the last 20 years received the attention it deserves in the natural sciences and, again, there is an extensive literature available. We would particularly draw your attention to the excellent SPNHC publication Preventive Conservation: Collection Storage (Elkin and Norris, 2019). This substantial and comprehensive volume was published on the cusp of our submitting this volume for publication so you will not see any specific references but resources such as this are part of our continuing learning as well as yours.

In our book we hope to address the need for consistency and quality decision making in the management of these large, highly variable and increasingly valuable collections.

Staff who formerly had limited areas of responsibility now need to make broad, strategic decisions but do not necessarily have the knowledge or training at the required level. A new type of collections manager is evolving with much wider responsibility and competence. We aim to raise awareness of new managers and established specialists alike to some of the tools, methods and approaches now available. Our ultimate aim is to prompt discussion rather than be over-reliant on existing facts. In the following paragraphs we will give you a summary of the areas that we cover in the next eight chapters.

Why are we writing this book?

We came to collections management from research or other academic backgrounds, mainly as users of collections ourselves. We had been practicing anthropologists and taxonomists in some of the world’s largest museums, working with the collections as the raw material to understand, classify and name our small pieces of the natural science jigsaw puzzle. We had all worked as collections managers or registrars and when we took management roles we all faced significant challenges. We joined at a time when there was in many museums a move to “put the management in collections management”, treating the management of our natural science collections through a business management lens. This was also a time when the funding for natural science and many other collections had been dwindling for many years and where our collections needed to justify their very existence.

We had all participated in reviews and surveys of collections and their management in a wide range of museums and herbaria mainly in Europe and the US and also our own institutions. We collectively noted that while the uses of collections by researchers were much the same, the ways in which they were managed, preserved and made accessible varied considerably within and between institutions. Accepted practice often overruled good practice and research drivers overruled collections care. How could this be redressed? We participated in international consortia and projects such as the Consortium of European Taxonomic Facilities (CETAF), the Collection Policy Board of CETAF (CPB) where we developed, among others, common guidelines for access and loans, and SYNTHESYS (www.synthesys.info/), where we were able to run courses to raise awareness of strategic thinking and new methodologies in the profession. In this book, we draw on these initiatives and the knowledge that we built up through sharing with our colleagues and, importantly, the things that we had to learn from scratch. We see this book as part of that process and something that complements these initiatives on a personal level. This is the book that we wish we had had when moving into management years ago.

What kind of collections and associated work do we address in this book?

This book primarily addresses natural science collections and includes traditionally preserved biological and geological specimens such as pinned insects, invertebrates in spirit, dried plants and mineral and fossil collections. This is not a manual on how to preserve and conserve plants and animals, how to set up a monitoring programme or how to achieve best practice in establishing museum documentation. Rather, we cover their management in museums, universities, herbaria and botanical gardens. We also include collections specifically preserved for molecular use such as frozen tissue and DNA, but only those housed and managed alongside traditional collections. However, while most of our experience, and hence the focus of the book, is on these collections, the principles extend to purpose-built biobanks of frozen tissues and living collections such as zoos, living plant collections in botanical gardens, viral, bacteria, cell and fungal cultures.

A summary of contents of this book

In Chapter 2 we explore the background to natural science collections, their historical development, changing value and usage and lead into their modern role as a physical and virtual infrastructure for a broad user community. Understanding their value beyond cultural artefacts is key to advocating for these collections and often one of the most rewarding parts of our jobs. Once the context has been established, we invite you to consider the arguments for the expenditure of time and resources beyond the cultural significance of your collections – what is the long-term responsibility of those managing collections and how has the context and ethical basis of collections changed? We give a brief summary of how natural science collections have been accumulated over 300 or more years and how they are used. Their role has broadened in recent years from describing, classifying, identifying and deciphering the evolutionary history of the natural world to supporting a range of vital scientific research from climate change to forensics and as a source for understanding the history of science. We are increasingly expected to be advocates for our collection and that could be deemed to be a responsibility as well as a duty. We give an overview of case studies and proof of concept projects that are available to help you justify the maintenance and housing of what can be an expensive enterprise. There are great benefits to be gained by natural science collections from forming partnerships and collaborations and examples range from sharing best practice to developing common access mechanisms.

In Chapter 3 we look at the advantage of strategic planning to achieve your goals, whether for specific areas such as conservation, more general plans for the whole institution or maybe an outline for a specific project. We emphasise the value of objective data over anecdotes and decision making based on the reality of sound data and illustrate the progression of strategy to application. What are your collections’ strengths and weaknesses or importance? We look at some of the many tools available for assessing collections to aid in prioritisation and to back up your case for expenditure of time, money and resources. We encourage you to think about why an assessment is needed, what and how it is being assessed and how data are presented to different audiences to gain maximum impact. We list the key elements of a plan, give some suggestions as to how the process can be made easier and give an example of the challenge of prioritising scarce resources over equally as important collections. Examples of existing strategies and planning exercises are given for you to examine critically. We look at measuring improvements over time and take a new look at well-established tools such as performance indicators and examine what makes a good indicator.

The increasing legal and ethical considerations that affect all collections are discussed in Chapter 4. We discuss how governance, which is an array of laws, regulations, polices and ethics might affect your strategic planning process and how they can help you achieve your goals. Policies in particular are a key element in minimising risks to collections, staff and institutional reputation. We also consider what makes a good policy and what is appropriate for natural science collections compared to other disciplines such as art. Collections organisations need to be aware of all these and ensure that they are carrying out their business in a legal and ethical way.

In Chapter 5 we explore the human element of our strategic approach. Collections rarely exist in isolation without any form of contact and interaction with people. They require expert input to ensure their long-term survival and maximise their accessibility, but very importantly to add and update the information associated with them. This added value is provided by individuals such as curators, collection managers, researchers, amateur specialists and volunteers. We look at some tools for identifying the competencies needed by your staff and volunteers to manage your coll...