The theory of probabilities is basically just common sense reduced to calculus; it makes one appreciate with exactness that which accurate minds feel with a sort of instinct, often without being able to account for it. If we consider the analytical methods that the theory gave rise to, the truth of the principles it relies on, the subtle logic that demands its application to solving problems, the public utility goods that is built upon it, and the extensions it has received and can still receive, given its application to the most important questions of natural philosophy and political economics; if we then observe that even in things that cannot be reduced to computation, probability theory allows the most reliable insights to guide us in our judgment, and that it teaches us to steer away from the illusions that often mislead us; we shall see that there is no science more worthy of our meditations, and whose results are more useful.

Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749-1827)

1.1 Stumped by a student

At the end of a lecture in probability and statistics I was giving at the École Polytechnique of Montreal, a trolling student came to test me with a simple-looking puzzle. A man has two kids. At least one is a boy. What is the probability that the other is a boy too?

After a few seconds of thoughts, I successfully gave the right answer, which, as we shall see, is not ½. The student acquiesced, and moved on to the next puzzle. Suppose you now learn that at least one of the kids is a boy born on a Tuesday. What is the probability that the other kid is a boy too?

This time, though, my answer was wrong. The student had stumped me.

The usual reflex is certainly to regard these two puzzles as mere mathematical games. Sure, there is a right answer. But that answer is only valid in a rigid and restricted mathematical setting. Solving these puzzles is useful in exercises or exams at school. But it’s only mathematics.

Yet, the puzzle of the troll student is just an ultra-simplified version of many questions that we face in our daily lives. Should I believe a medical diagnosis? Is the presumption of innocence justified? Do judges racially discriminate? Is terrorism worrying? Can one generalize from one example? From a thousand? A million? Is the argument of authority worth anything? Are financial markets trustworthy? Are GMOs harmful? Why would science be more right than pseudosciences? Are robots about to conquer the world? Is capitalism wrong? Does God exist? What’s good and what’s bad?

For most, such questions have absolutely nothing to do with mathematics. And indeed, math alone is insufficient to address such questions. World hunger will not be solved by only proving theorems. Nevertheless, math likely has a lot to offer. It can help better structure our thinking, identify key challenges, and provide unexpected solutions. This is why many endeavours are more and more mathematized - including humanitary aid1.

Despite the flourishing of mathematical models, it seems that most of us still want to distinguish the “real world” from academic courses that schools force us to take. In particular, the real world, it is often said, far transcends the framework of mathematics. As a result, mathematical theorems never seem to really apply to reality. How stupid must one be to think that mathematics has anything to say about the equality of rights2 ?

Sadly, rejecting the usefulness of mathematics is not merely a bad-student reflex. Even years after failing the troll student puzzle, I had not yet realized that my mathematical mishap revealed my inability to correctly reason about the real world. I had not understood that a better understanding of the puzzle would be key to better analyze my traveling friends’ advice to plan my next trip - we’ll get there.

1.2 My path towards Bayesianism

Granted, I did solve the troll student puzzle later that day, after some obscure and mysterious computations. But it was only three years later, in early 2016, when I investigated the frequentist-Bayesian debate, that I really took the time to meditate about the puzzle. Most importantly, at last, I finally took it out of its confined mathematical setting.

In particular, for the three years that followed, nearly once a day, I kept thinking about the magical equation that solves this puzzle. To my greatest pleasure, this mysterious equation started to reveal its secrets to me. Slowly but surely, this brilliant equation was seducing me. I began to see it everywhere. Months after months, my mind got flooded with the sublime elegance of this untameable equation. It was too much. I had to write about it. And I had to do this well. This is how, towards the end of 2016, I began the writing of the book you have just started.

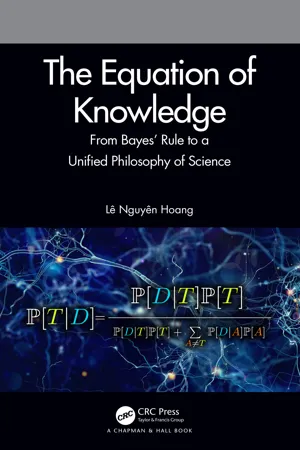

The untameable equation I am talking about is what I like to pompously call the equation of knowledge. But mathematicians, statisticians, and computer scientists better know it as Bayes’ rule.

Bayes’ rule is a mathematical theorem of remarkable simplicity. It’s a compact equation, which is often taught in high school. It has a one-life proof, and only relies on multiplication, division, and the notion of probability. In particular, it seems vastly easier to learn than many other concepts in mathematics that high school and university students are asked to master.

And yet I’d claim that even the best mathematicians do not understand Bayes’ rule - and there is even some mathematics that explains our inability to grasp this equation! More modestly, there is absolutely no doubt that I still do not understand Bayes’ rule. Indeed, if I did, I would have immediately seen how the fact that at least one kid is a boy born on a Tuesday affects the likely gender of his sibling. I would have...