So, here is a story I know.

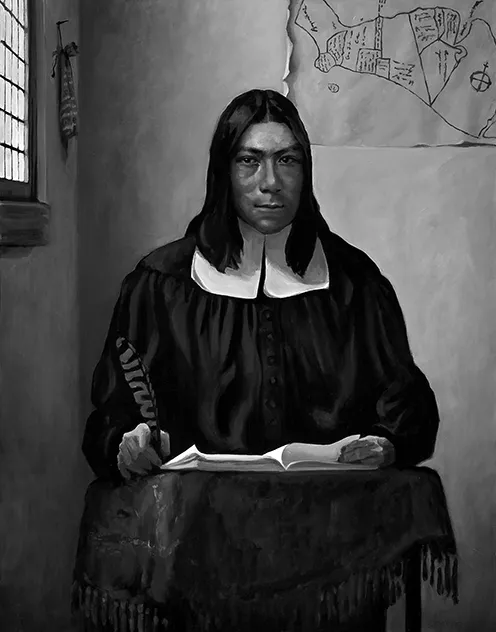

It is sometime in the fall of 1663, and a young scholar sits at his roughhewn wooden desk in his room at Harvard College, quill in hand, staring at a sheet of paper which takes on a ghostly glow in the candlelight before him. He is pensive for a moment as he scans the two words he has previously penned, Honoratissimi Benefactores, “Most Honored Benefactors.” He is writing to a man (to a group of men really) he has never met and will never meet in his lifetime. But it has been impressed upon him that he owes them something—a measure of gratitude if nothing else—and, although tried and true forms exist for expressing such gratitude, there is always, apart from everything else, some degree of artistry involved in the gesture, a flourish demonstrating both humility and expertise. He knows these protocols well and has often seen them in action, as exhibited by his father and grandfather before him—polished diplomats both who understood the significance of fashioning the proper word to the proper moment, how a sentence spoken one way might result in war, whereas the same words offered in a slightly altered arrangement might ensure yet another generation of peace. It is because of his place in this lineage of wise men and diplomats that he has been sent here to Harvard to study the classics, ancient philosophy, the mysteries of the cosmos, to master Latin, Hebrew, and Greek, and become intimate with the word of God as professed in the Congregationalist meeting houses of the Massachusetts Bay Colony—to become a proselytizer of that faith, in fact, should he ever manage to complete his studies and return home to his village.

Outdoors, a rush of wind shakes the tall oaks, rattles the windows, and calls up a low moan from the channel of the hearth where the fire flares to life for a brief moment, before settling once more to its guttering flame. As though attuned to something the wind has foretold, he turns his head slightly to one side, absorbing some sensory transmission from the sudden shift in the ether. He dips his pen in the well and begins scratching away at the paper, exercising his most precise penmanship and taking care not to rest his hand and smudge the ink. From time to time he pauses, sends his breath over the page to harden the tracks he has left upon its surface, and references the primer sitting open on the table beside him. During these pauses, he unconsciously uses his free hand to stroke the leather hide of the medicine bundle he wears fastened around his neck, running his thumb and forefinger along its worn, pliable surface and feeling the resistance of the objects within. He writes:

Historians tell of Orpheus, the musician and outstanding poet, that he received a lyre from Apollo, and that he was so excellent with it that he moved the forests and rocks by his song. He made huge trees follow behind him, and indeed rendered tamer the most ferocious beasts. After he took up the lyre he descended into the nether world, lulled Pluto and Proserpina with his song, and led Eurydice, his wife, out of the underworld and into the upper. The ancient philosophers say this serves as a symbol to show how powerful are the force and virtue of education and refined literature in the transformation of the nature of barbarians.2

The young man who writes has been tasked with his assignment by none other than John Winthrop Jr., governor of the Connecticut Colony and son of the late, revered, Massachusetts Bay Colony governor of the same name. And, like most advanced students, he has a pretty good idea of what he is being asked to perform. After all, he has been living among these intruders upon his land for nearly a decade, learning their language, their customs, their beliefs, and biases. He knows they have a dim view of the people of the morning light, the Wampanoags—his people—holding in utter contempt the traditions and beliefs he has cherished since childhood. But he has been sent here to learn the ways of these foreigners and he is growing in the art of diplomacy. And so, he places a great deal of carefully crafted pious talk in his letter, thanking his “benefactors” for their “wisdom and infinite compassion” in the work of “bringing blessings to us pagans” and for leading himself and his people toward Christian light and salvation. He wonders for a moment if they will even notice how, in congratulating them for their refined arts and letters, he draws upon an example from western culture’s oral tradition—the Greek bard—a figure he readily equates with the storytellers and medicine men (he knows them as “powwows”) of his own people, who, like Orpheus, are capable of making water burn, rocks move, trees dance with their arts.3

He concludes his letter by informing his far-off English patrons that they are, in their mercy, like “aqueducts in bestowing all these benefits on us.” In his own culture, too, water is sacred, the sustainer of life itself, and he is grateful for the gifts it brings. He has never seen an aqueduct, but he has read enough about them and feels his readers will appreciate the allusion. And finally he signs off, “Most devoted to your dignity: Caleb Cheeshateaumauk.” The letter will be handed over to Governor Winthrop and soon travel overseas to London, where it will be received by Robert Boyle, president of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England, where it will serve as an impressive proof of the progress being made in educating the “poor Indians” in Christian knowledge. The letter will be preserved in Boyle’s papers, where it will be rediscovered a few centuries later and held up as the earliest known extant example of writing by a Native American in the English colonies. The letter is written entirely in Latin.

I will often begin a semester by throwing Cheeshateaumauk’s letter, untranslated, up on the big screen and asking students to guess at what it is. The point, of course, is not necessarily to stump them, but to begin to break down preconceived notions of what it meant to be Native American during the early era of colonial contacts. Typically, one or two students will recognize (or make a lucky guess) that the text is in Latin. But it will take a while, even in a class specifically devoted to Native American literature, for anyone to hit upon the notion that this is, in fact, a letter written by a Native American, and they will be surprised to learn it is the first such piece of writing on record. It is, put quite simply, a story they have never heard before.

In the discussion that follows, and with translation in hand, I will ask them to unpack the allusions to Orpheus. We will think through some of the Christian language and consider the explicit denigrations of Cheeshateaumauk’s own people as grateful “pagans” and “barbarians,” asking how much of this is sincere and how much is performance? Students will want to know what Cheeshateaumauk was doing at Harvard in the first place. Was he forced against his will to learn English ways and letters, or would he have his own reasons for being there? Is Cheeshateaumauk truly grateful for the education he has undertaken, or is he withholding his true feelings for the sake of expediency? If one reads between the lines, is it also possible to locate an implied critique of colonialism in his letter? Why, for instance, does Cheeshateaumauk use a figure from oral tradition to represent his gratitude for learning English “letters?” And why, if the allure of western tradition as represented by Orpheus is so powerful and persuasive, does Cheeshateaumauk go on to suggest that the “barbarians” need be “secured like tigers and must be induced to follow”?4 Does this not imply coercive force rather than a charm offensive? I do not have definite answers to all these questions myself, despite my ability to draw informed inferences based on my knowledge of this era, but I am always interested to see where the conversation will lead and if students can come up with persuasive interpretations on their own that help to decolonize the text of this letter.

Cheeshateaumauk certainly does not fit the model most people hold in their heads for seventeenth-century Indians. But by no means was he a complete exception either. Harvard College was founded with the express intent written into its charter to educate the “poor heathen” and bring them out of their presumed state of eternal darkness.5 The Wampanoags, who, for better or worse, were neighbors to the new colonists and had to devise ways of getting along with them, found it in their interest to send emissaries, such as Cheeshateaumauk, from established leading families, to learn the ways of western culture and form a first line of political and diplomatic defense against settler ambitions. As we’ve already witnessed in the case of Pocahontas, this was a practice put in motion by many Native people, independent of one another, across the Northeast. Caleb was, in fact, joined at Harvard by a number of other Native students. They were housed in what became known as the Indian College, the first structure of brick and mortar to be erected on the newly founded campus. This same building would also come to house the Cambridge Press, the very first press in North America, which was manned by a young member of the Nipmuc tribe named Wowaus, but known in the colonies by the Christian name given him, James Printer.

Interestingly enough, given how Native people are rarely equated with literature and printing, the Indian College became the center of literary production in the colonies. Not only were sermons, broadsides, and Harvard commencement speeches printed there, with James Printer himself setting the type, but in 1663 the first Bible to be printed in the colonies was birthed from the press at the Indian College. The Puritan preacher John Eliot, so-called Apostle to the Indians, is listed as the editor and translator of this ambitious production, but, in reality, the greater part of that work was done by a group of writing Indians such as Cheeshateaumauk, Joel Hiacooms, Job Nesuton, John Wampus, James Printer, and others. The Bible was printed in a local dialect of the Algonquian language with the goal of using it to convert Natives to Christianity.

It didn’t work.

Not really. It would take war, disease, fragmentation of families and communities, and ultimately decades of marginalization and economic isolation to finally accomplish this goal. But the Algonquian Bible nevertheless stands at the forefront of Native North Americans picking up the pen in the seventeenth century and beginning their long engagement with western notions of literacy.