Literacies that Move and Matter

Nexus Analysis for Contemporary Childhoods

- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Expanding the definition and use of literacies beyond verbal and written communication, this book examines contemporary literacies through action-focused analysis of bodies, places, and media. Nexus analysis examines how people enact and mobilize meanings that are largely unspoken. Wohlwend demonstrates how nexus analysis can be used as a tool to critically analyze and understand action in everyday settings, to provide a deeper understanding of how meanings are produced from a mix of modes in daily social and cultural contexts. Organized in three sections—Engaging Nexus, Navigating Nexus, and Changing Nexus—this book provides a roadmap to applying nexus analysis to literacy research, and offers tools to enable readers to compare methods across contexts.

Designed to help readers understand the theoretical and methodological assumptions and goals of nexus analysis in classroom and literacy research, this book provides a comprehensive understanding of the theory, framework, and foundations of nexus analysis, by using multimodal examples such as films and media, artifacts, live action performances, and more. Each chapter features consistent sections on key ideas and methods, and a description of procedures for replication and application.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Navigating Nexus

4

READING ACTIVITY

Chapter Overview

| Key Scholars | Brian Street, James Paul Gee, Ron Scollon, Suzanne Wong Scollon |

| Key Concepts | Literacy as Social Practice |

| Shared Meaning–Making and Cultural Participation | |

| Situated Literacies | |

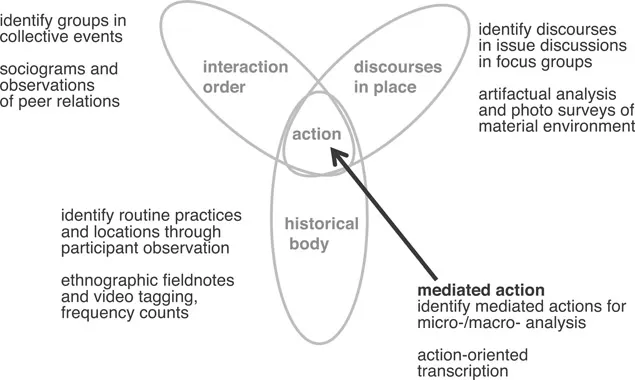

| Methods Focus | Filtering Ethnographic Data to Locate Nexus

|

| Some Methods Mapped to Concepts | |

| Discourses in Place (DP): photo surveys => material meanings in sensory environment | |

| Interaction Order (IO): interviews and sociograms => typical groups | |

| Historical Body (HB): frequency counts => routine practices | |

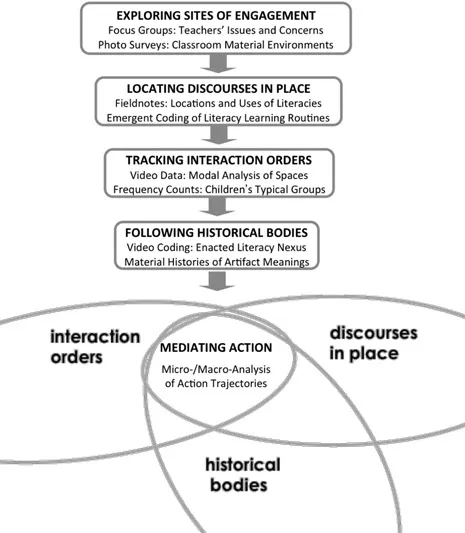

| Navigating Nexus | Inquiry 6: What Do I Do With All This Data? Using Three Flows as Filters |

| Inquiry 7: What’s at Issue? Asking Participants | |

| Inquiry 8: Which Things Matter Here? Locating Discourses in Place | |

| Inquiry 9: Who’s Usually With Whom? Finding Interaction Orders | |

| Inquiry 10: What Are People Expected to Do? Revealing Historical Bodies | |

| Inquiry 11: What Is Literacy Doing Here? Finding Nexus Within an Activity Model | |

| Examples | Classroom Video and Teachers’ Concerns |

| Playing to Read | |

| Reading to Play | |

Nexus and Situated Literacies

- the unspoken meanings of materials and designs that make up discourses in place

- the multimodal production of spaces of belonging that make up interaction orders

- the automatic practices and engrained expectations that make up historical bodies

- The first filter gives you a sense of what matters here as you learn about core issues from participants (IO) and seek to understand how their issues are reflected in the material environment (DP) and routine practices (HB) (see examples in the next section).

- The next three filters help you focus systematically on each flow (DP, IO, or HB) as you collect initial data and more of the nexus becomes apparent.

- The filters funnel data to moments for micro-/macro-analysis of an action in the convergence of these flows so that you can explore its impact and potential for changing nexus.

- Finally, the last steps are to think practically and imaginatively to improvise and reassemble the typical ways of doing things by altering this small action as a means to help participants reshape the nexus.

Exploring Potential Sites

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- EXPANDED TABLE OF CONTENTS

- List of Excerpts from Previous Publications

- Photo Credits

- Series Editor Introduction

- Preface

- Engaging Nexus

- Navigating Nexus

- Changing Nexus

- Appendix A: Research Studies Mapped to Methods and Publications

- Appendix B: Glossary of Key Terms

- Index