- 162 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Turning Psychology into Social Contextual Analysis

About this book

This groundbreaking book shows how we can build a better understanding

of people by merging psychology with the social sciences. It is part of a

trilogy that offers a new way of doing psychology focusing on people's

social and societal environments as determining their behaviour, rather than

internal and individualistic attributions.

Putting the 'social' properly back into psychology, Bernard Guerin turns

psychology inside out to offer a more integrated way of thinking about and

researching people. Going back 60 years of psychology's history to the

'cognitive revolution', Guerin argues that psychology made a mistake, and

demonstrates in fascinating new ways how to instead fully contextualize the

topics of psychology and merge with the social sciences. Covering perception,

emotion, language, thinking, and social behaviour, the book seeks to

guide readers to observe how behaviours are shaped by their social, cultural,

economic, patriarchal, colonized, historical, and other contexts. Our brain,

neurophysiology, and body are still involved as important interfaces, but

human actions do not originate inside of people so we will never fi nd the

answers in our neurophysiology. Replacing the internal origins of behaviour

with external social contextual analyses, the book even argues that thinking

is not done by you 'in your head' but arises from our external social, cultural,

and discursive worlds.

Offering a refreshing new approach to better understand how humans

operate in their social, cultural, economic, discursive, and societal worlds,

rather than inside their heads, and how we might have to rethink our

approaches to neuropsychology as well, this is fascinating reading for

students in psychology and the social sciences.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1 Where psychology went wrong 60 years ago

An erroneous turn at the fork in the Gestalt road

Turning psychology inside out

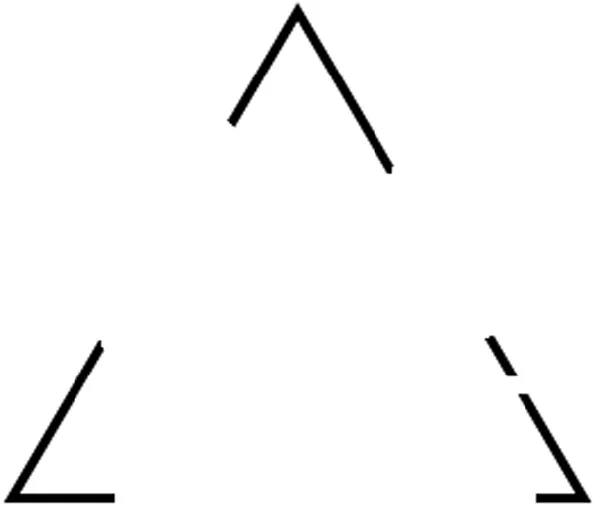

What can we learn from a broken triangle?

What did the Gestaltists do with this?

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Information

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Where psychology went wrong 60 years ago: An erroneous turn at the fork in the Gestalt road

- 2 Going back to the ‘fork in the road’ and starting a fresh contextual approach

- 3 Language is a socially transitive verb—huh?

- 4 How can thinking possibly originate in our environments?

- 5 Contextualizing perception: Continuous micro responses focus-engaging with the changing effects of fractal-like environments?

- 6 Contextualizing emotions: When words fail us

- 7 The perils of using language in everyday life: The dark side of discourse and thinking

- 8 Weaning yourself off cognitive models

- Index