- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The saga of the seventh-century Chinese monk Xuanzang, who completed an epic sixteen-year journey to discover the heart of Buddhism at its source in India, is a splendid story of human struggle and triumph. One of China's great heroes, Xuanzang is introduced here for the first time to Western readers in this richly illustrated book.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Xuanzang by Sally Wriggins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

Asian PoliticsONE

THE PILGRIM & THE EMPEROR

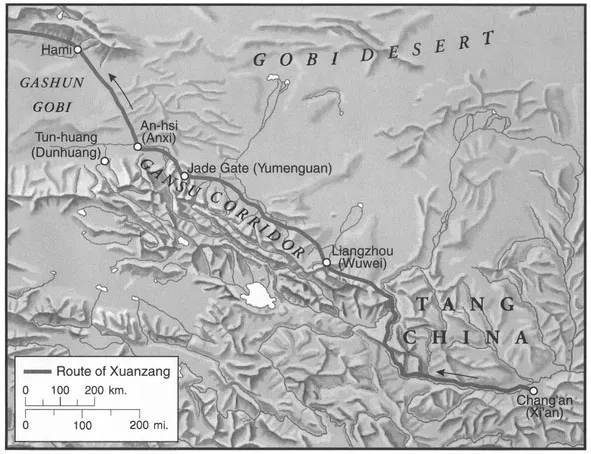

MAP 1.1 Itinerary of Xuanzang on the Silk Road in China (from Chang'an to Hami) (Philip Schwartzberg, Meridian Mapping)

IN 629 C.E. A YOUNG MONK named Xuanzang left China with a warrant on his head; he departed in secret by night. He made his way safely past five watchtowers in the desert and the Jade Gate, the last outpost of the Tang Empire, The fears of this solitary pilgrim were not over, for he was traveling against the wishes of the Emperor Taizong (T'ai-tsung, 626-649 C.E.) (Fig. 1.1).

This young ruler of the Tang dynasty had little sympathy for Buddhism at the time and did not want Xuanzang or any other of his subjects in the dangerous western regions. His power was far from secure and he was still grappling with the hostility and even treachery of several of the peoples of Central Asia. Disobeying the emperor would carry a heavy price, but Xuanzang was determined to go on a pilgrimage to the holy land of Buddhism in India.1

In April 645, after his 10,000-mile quest for truth to India, the pilgrim returned and approached the Tang capital Chang'an, modern Xi'an. The news of his arrival soon spread; the streets were filled to overflowing, so much so that Xuanzang could not make his way through the crowds. People had heard about his pilgrimage to far-off and strange lands and wanted to see him. He was obliged to spend the night by a canal on the outskirts of the city. The magistrates, fearing that a large number of people would be crushed in the crowd, ordered everyone to stand quietly and burn incense. The emperor was away at the time, but an audience was arranged. A huge procession of monks carried the relics, images, and books that Xuanzang had brought back with him from India. The return of a hero.

In the sixteen years between Xuanzang's lonely departure and his triumphant reentry in 645, both the pilgrim and the emperor had succeeded in the eyes of the world. The twenty-seven-year-old fugitive had become China's best-known Buddhist and one of the most remarkable travelers of all time.2 The thirty-year-old emperor, who was of Turkish-Chinese descent and therefore an expert horseman, had become one of China's greatest emperors, presiding over the expanding Tang Empire (Fig. 1.2)

Xuanzang accomplished his religious mission and returned safely with a large collection of Buddhist scriptures. He had seen "traces not seen before, heard sacred words not heard before, witnessed spiritual prodigies exceeding those of nature." He had consulted with the rulers of the oases of the Northern and Southern Silk Roads; the Great Khan of the Western Turks; King Harsha, uniter of northern India; and many potentates in between. He would remember a close friendship with the head of India's most illustrious monastery all his life. He had crossed the most dangerous rivers and three of the highest mountain ranges in Asia (Fig. 1.3).

![FIGURE 1.1 Portrait of the Emperor Taizong, who at first forbade the young monk Xuanzang to go to India and after the trip asked him to write an account of his journey, which is one of the principal sources for this book (The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs. Edward S. Harkness, 1947 [48.81 lj])](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/1629006/images/fig00005-plgo-compressed.webp)

FIGURE 1.1 Portrait of the Emperor Taizong, who at first forbade the young monk Xuanzang to go to India and after the trip asked him to write an account of his journey, which is one of the principal sources for this book (The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs. Edward S. Harkness, 1947 [48.81 lj])

Not only had the new Tang emperor consolidated his power in China; he had conquered Central Asia. First he defeated the Eastern Turks in Mongolia in 630 C.E. Then he turned his attention to the Western Turks. By a curious stroke of fate, the Great Khan of the Western Turks was murdered shortly after Xuanzang's visit; six months later his mighty empire collapsed. The Tang emperor then began to reestablish protectorates over the oases of the Northern and Southern Silk Roads, where the pilgrim had also been. As a result of these conquests, China exercised direct control as far as the Pamirs. On occasion, the emperor extended his power through diplomacy, such as when he arranged a marriage alliance with a Tibetan royal family. He had already sent two Chinese envoys to King Harsha in India in 643 C.E. after Xuanzang's visit. Religious missions such as Xuanzang's would extend the reach of China even bevond the Pamirs.

![FIGURE 1.2 Relief from the tomb of the Emperor Taizong (ruled 626-649 C.E.), showing a general removing an arrow from a wounded horse (University of Pennsylvania Museum [Neg. #23298])](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/1629006/images/fig00006-plgo-compressed.webp)

FIGURE 1.2 Relief from the tomb of the Emperor Taizong (ruled 626-649 C.E.), showing a general removing an arrow from a wounded horse (University of Pennsylvania Museum [Neg. #23298])

What a difference in background and temperament of these two men! Brought up with Confucian values, Xuanzang was a bookish boy who read Confucian classics and became a scholarly Buddhist intellectual. But he broadened his intellectual skills, and far from staying in a monastic cell, he overcame robbers and pirates and became a mountaineer and survivor in the desert. The emperor, whose early education was horsemanship and archery, was a rough soldier and heroic warrior

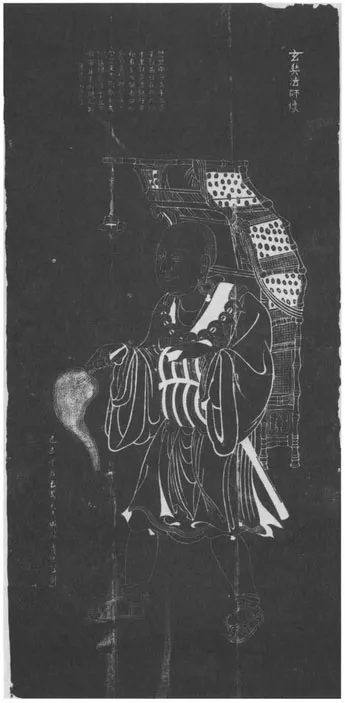

FIGURE 1.3 Copy of a traditional fourteenth-century portrait of Xuanzang with a modem-looking frame pack filled with the Buddhist scriptures he brought with him from India. Portrait from a rubbing taken from a stele at Xuanzang's burial place, at the Temple of Flourishing Teaching, outside Xi'an. (Courtesy Abe Dulberg, photographer)

who had come to the throne after assassinating his elder brother. Yet the emperor in the early years of his reign came to be regarded as a moderate, frugal, and wise Confucian ruler who sought the advice of his ministers and was concerned for the welfare of his people,3 As a final irony, it was Xuanzang's secular knowledge of foreign affairs gained from years of arduous travel that interested the Tang ruler, although toward the end of his life, the ailing emperor changed his views on Buddhism, sought out Xuanzang for solace, and accepted him wholeheartedly as his spiritual mentor.4 At the first meeting of the emperor and the pilgrim in 645, both men were at the height of their careers. The experiences of the Chinese pilgrim and the political interest of the emperor coincided in a remarkable way. With the expansion of his new empire, the emperor needed firsthand information about the successes and failures of his imperial policies. Xuanzang was the ideal informant. The emperor questioned the forty-three-year-old monk in detail about the rulers, climate, products, and customs of the countries he had been through. Impressed by Xuanzang's knowledge of foreign lands, Taizong asked him to be a minister to advise the emperor on the new Asian relationships and problems of his kingdom. Xuanzang declined. Then the emperor requested that he set down a detailed account, country by country, of the western kingdoms that he had visited. What interested Xuanzang the most—information on the monks, their schools of philosophy, and especially the monuments and stories of the Buddha—were matters of indifference to his patron.

No matter. Writing an account of the western regions was a new kind of request for Xuanzang who was used to those who sought his advice on religion or philosophy. A man of many parts, adventurer, intellectual, theologian, priest, and ambassador, he had given spiritual advice and inspiration to many political leaders and potentates in Central Asia. A "Prince among Pilgrims," this Buddhist monk moved easily in both religious and secular worlds. His powerful personality had impressed both the Emperor Taizong and the great Indian King Harsha. A man of unusual flexibility open to the new and strange wherever he found it, Xuanzang was an ideal observer of foreign cultures.

Studying in Monasteries

Who was this Chinese pilgrim, and how did he happen to go on his long journey? According to his biographer, Xuanzang was born near Luoyang in the province of Henan in 602. He was the youngest of four sons, an heir to a long line of literati and mandarins. His grandfather had been an official in the Qi (Ch'i) dynasty ¡479-501 C.E.) and held the post of eminent national scholar. His father had been well versed in Confucianism and was also distinguished for his superior abilities and elegance of manner. However, this Confucian gentleman preferred to busy himself in the study of his books and pleaded ill health rather than accept offers of government service at the time of the decaying Sui dynasty (581-618 C.E.).

Xuanzang was brought up in a Confucian household, At the age of eight he amazed his father with his filial piety, a strong virtue in Confucianism. He even began to study the Confucian classic books about this time. But the intellectual vitality of Confucianism was waning,5 and Xuanzang's older brother became a Buddhist monk. He took an interest in his younger brother and saw to it that he began to study Buddhist scriptures at his monastery in Luoyang at a young age.

Xuanzang was the kind of serious boy who was old before he was young. When he was only twelve years old, an unexpected royal mandate announced that fourteen monks were to be trained and supported by the state at his brother's monastery in Luoyang, the eastern capital of the Sui dynasty. Several hundred candidates applied at the Pure Land Monastery for this important ordination. The young adolescent Xuanzang loitered at the monastery gate until the imperial envoy, who was about to supervise the ceremony, engaged him in conversation. "What is your name? Your age?" And when Xuanzang revealed how very much he wanted to be a monk, the official asked him why. "My only thought in taking this step, " he replied, "is to spread abroad the light of the Religion of Tathagata (Buddha!."6

Such an unexpected and formal reply impressed the official, who recognized the boy's remarkable qualities from his eagerness, confidence, and modesty. The official selected him as one of the novices to be ordained despite his youth, for, as he explained to his fellow officials, "To repeat one's instructions is easy, but true self-possession and nerve are not so common."7

For the next five years Xuanzang lived with his brother at the Pure Land Monastery. He plunged into the study of Buddhist scriptures, both the austere doctrine of early Buddhism and the mystical doctrine of the Greater Vehicle, or Mahayana. Xuanzang was irresistibly drawn to this later Buddhism, whose two key words were "Emptiness," signifying the object of wisdom, and "Bodhisattvas," or Enlightened Beings, who postponed their own salvation for the sake of others (Fig. 1.4.).8

His philosophical studies were interrupted in 618 C.E. when the Sui dynasty collapsed. Because of the anarchy that followed its downfall and the civil war between the Tangs and their rivals, many parts of the empire fell into chaos.9 Xuanzang and his brother fled first to Chang'an in the northwest, which the Tang rulers had proclaimed their capital. They found the city swarming with soldiers, so the two brothers, along with a large community of monks who were gathering from various parts of the empire, made their way to Chengdu, in Sichuan. Xuanzang and his brother spent two or three years there studying the different schools of Buddhism.

FIGURE 1.4 Wall painting and sculpture in one of the earliest Dunhuang Caves in China. Center figure is a Bodhisattva, or Maitreya (these are beings who postpone their own salvation so that they may help others). (The Lo Archive)

Xuanzang's biographer compared the two young men: "His elder brother . . . was elegant in his manners and sturdy physically just like his father., . . His eloquence and comprehensiveness in discussion and capacity to edify people were equal to those of his younger brother." He continued, "But in the manner of loftiness of mind, without being affected by worldly attachments; in profound researches in metaphysical aspects of the cosmos; in ambition to clarify the universe . . . and in the sense of self respect even in the presence of the Emperor," Xuanzang surpassed him.10

In 622, when he was twenty, Xuanzang was fully ordained as a monk. Shortly afterwards he left his brother behind in Chengdu and returned to the capital.

Preparing Himself in Chang'an

Chang'an had much to offer Xuanzang. It was the greatest city in China—perhaps in the entire medieval world. Tang historical sources are so detailed that we know, for example, that it occupied an area of more than 30 square miles.11 Rome at its height occupied 5.2, square miles. Chang'an, a city of a million people in the seventh century, became the center of the great culture of the Tang dynasties. In 742 C.E. its population had swelled to two million inhabitants, of whom five thousand were foreigners.12

With its rich cultural life, prosperity, and the variety of nationalities that came to live there, Chang'an was a radiating center of Asian civilization. New stimuli from northern India and the kingdoms of Central Asia enriched Chinese Buddhism and made it the most lively and influential system of thought in its day. From Iran and Central Asia came other new religions, including Islam, Zoroastrianism, Manichaeanism, and Nestorian Christianity. Together with these intellectual and spiritual influences came many new developments in the arts, ranging from music and the dance to metal working and fine cuisine, as well as important technical and scientific influences in mathematics and linguistics. A galaxy of poets and artists were also part of this glittering capital. The latest in Buddhist doctrine and in pictorial models, the newest in entertainment and fashion, could be found in Chang'an....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Maps

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Spelling and Pronunciation

- 1 THE PILGRIM & THE EMPEROR

- 2 THE OASES OF THE NORTHERN SILK ROAD

- 3 THE CROSSROADS OF ASIA

- 4 THE LAND OF INDIA

- 5 PHILOSOPHERS & PIRATES IN NORTHERN INDIA

- 6 THE BUDDHIST HOLY LAND

- 7 NALANDA MONASTERY & ENVIRONS

- 8 PHILOSOPHERS, ROCK-CUT CAVES & A FORTUNE-TELLER

- 9 THE JOURNEY HOME TO CHINA

- 10 BACK IN CHINA

- AFTERWORD: THE LEGACY OF XUANZANG

- Glossary

- Notes on Illustrations

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- About the Book and Author

- Index