- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

What do we mean by 'art'? As a category of objects, the concept belongs to a Western cultural tradition, originally European and now increasingly global, but how useful is it for understanding other traditions? To understand art as a universal human value, we need to look at how the concept was constructed in order to reconstruct it through an understanding of the wider world. Western art values have a pervasive influence upon non-Western cultures and upon Western attitudes to them. This innovative yet accessible new text explores the ways theories of art developed as Western knowledge of the world expanded through exploration and trade, conquest, colonisation and research into other cultures, present and past. It considers the issues arising from the historical relationships which brought diverse artistic traditions together under the influence of Western art values, looking at how art has been used by colonisers and colonised in the causes of collecting and commerce, cultural hegemony and autonomous identities.World Art questions conventional Western assumptions of art from an anthropological perspective which allows comparison between cultures. It treats art as a property of artefacts rather than a category of objects, reclaiming the idea of 'world art' from the 'art world'. This book is essential reading for all students on anthropology of art courses as well as students of museum studies and art history, based on a wide range of case studies and supported by learning features such as annotated further reading and chapter opening summaries.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access World Art by Ben Burt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

WESTERN PERSPECTIVES

How ideas of art that developed in Europe were applied to other cultures, both present and past, with the expansion of Western knowledge of the world through exploration, commerce, and colonization.

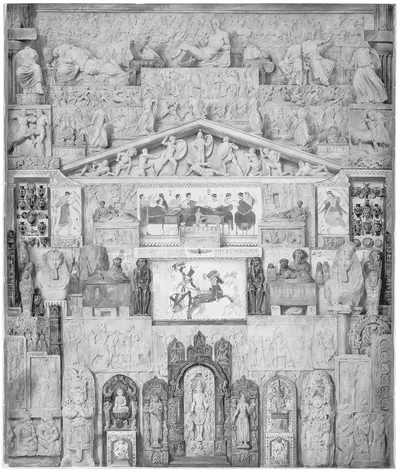

1 THE ORIGINS OF ART

We begin by looking at how the Western idea of art was constructed during the past five hundred years, while Europeans were exploring the world and developing their claim to be at the apex of human civilization. While distinguishing their own most valued products as art, they also collected and classified the artefacts of the world, founding museums, galleries, and academies to serve concepts of art that were inherently ambiguous and contested.

Outline of the Chapter

- New Worlds and Histories

A historical review of European expansion, the Renaissance of ancient Mediterranean culture, and the idea of art. - Industrial and Intellectual Revolutions

The roots of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment and the development of art connoisseurship - British Museums

The collection and classification of artefacts since the eighteenth century, with a focus on the British Museum. - Politics and Commerce, Art and Craft

A preliminary look at the Western culture of collecting.

Art originated in Europe, but not, as Europeans tend to assume, with the cave paintings of the Paleolithic. Rather, it began only a few hundred years ago as a cultural tradition of distinguishing the creation of particular artefacts and activities that communicate significant ideas and emotions. Th is was not a simple matter even when Europeans applied it to their own culture, and it produced all sorts of contradictions when applied to other peoples’ artefacts as they were drawn into ever closer relationships through globalization. If the concept of art is indeed to have the universal application that “world art” implies, it is important to understand how it came to mean what it does through the history of its construction in Europe and its application to the rest of humanity.

NEW WORLDS AND HISTORIES

It was five hundred years ago, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, that peoples around the world began to have the generally unpleasant experience of being “discovered” by Europe. In the process, Europeans began to come to terms with the widening horizons, as well as the wealth and power, that the onset of globalization brought them in the centuries that followed.

In the 1490s, the Spanish reached the Caribbean, and the Portuguese found a route around Africa to India. In the 1500s, the Spanish began conquering territory in and around the Caribbean, and the Portuguese founded a colony at Mozambique. In the 1510s, the Portuguese captured Malacca in Malaya and began trading with southern China, while the Spanish began the conquest of the Aztec empire of Mexico. In the 1520s, the Portuguese began to colonize Brazil, and the Spanish sailed around the world. In the 1530s, the Spanish conquered the Inca empire of Peru. By the mid-sixteenth century, Europeans were trading South American silver for Indian cotton cloth, Southeast Asian spices and Chinese silks, and were shipping Africans as slave labor to work sugar plantations in the Americas. By the early seventeenth century, the British, French, and Dutch were establishing their own overseas empires, in competition with the Spanish and Portuguese.

The riches brought home to Europe helped shift the balance of power in society, challenging the political and intellectual certainties of the state and church. As prominent men increasingly bought their power with commercial wealth, rather than extracting wealth by political power under feudal relationships, they became increasingly unwilling to accept theological justifications for the old order. It was no longer enough to insist on a single absolute divine truth, from which knowledge had to be deduced rather than added to by new experience and research. In their search for new explanations for their changing experience, Europeans discovered an ancient past for themselves at the same time that they were discovering the wider world. Th e “age of discovery” also saw a revival of ancient Mediterranean culture and the emergence of new ways of thinking, which led in time to new cultural traditions of science, and of art.

The revival of ancient knowledge and skills produced new theories of history. Following the fourteenth-century Italian philosopher Francesco Petrarch, it came to be generally agreed that civilization had gone through a cycle of “ages.” Growing from “archaic” beginnings, it had achieved its highest point in “classical” Greece and Rome (when, among other things, painting and sculpture were perfected), had declined with the Roman empire under Christianity and the barbarian invasions, been forgotten in the ensuing “dark ages,” recovered somewhat in the transitional Christian “middle ages,” and eventually revived with the rediscovery and rebirth, or “renaissance,” of antiquity from the mid-fourteenth century. Later, in the eighteenth century, Europeans decided they had seen through the ignorant illusions of their predecessors, in the “enlightenment,” which paved the way for “modernity.”

This way of viewing European history, in which civilizations rose, fell, and rose again to reach the heights of contemporary achievement, laid the ground for later theories of world history, including why most of the newly discovered peoples had never risen in the first place. It was no coincidence that among the ancient Mediterranean practices revived in the Renaissance was commercial slavery, under which it was acceptable to force supposedly less civilized peoples, such as Muslims, Amerindians, and Africans, to work for the benefit of Christians.

ART AND ARTISTS

The cycle of history was realized, among other things, in a revival of the ancient conventions for painting and sculpture, which required that the appearance of things be idealized to represent the beauty of nature. For the Florentine sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti in the mid-fifteenth century, this revival was signaled by the paintings of Giotto in the early fourteenth century. While the skills of making things could be loosely described as “arts,” practiced by artisans, Renaissance painters and sculptors were increasingly treated as “artists,” who, analogous with poets, pursued an intellectual discipline under divine inspiration. By the mid-sixteenth century, the standards for assessing their work were being set down in influential writings that focused on prominent artists and their influence upon one another, allowing a history of styles, schools, and periods to be constructed. Th e Italian architect and painter Georgio Vasari in Th e Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects described how, in the cycle of decline and revival from ancient times, the individual creativity of contemporary artists had attained a divine “grace.” Vasari and like-minded artists founded academies of art under royal patronage throughout Europe from this time, setting standards derived from Plato’s concept of perfect forms, which the mind could conceive as underlying the imperfect world of experience.

Classical works provided models and inspiration for an emerging hierarchy of artistic value, formalized by the national academies and explained in the 1660s by André Félibien, art historian of the French royal court:

the pleasure and instruction we receive from the works of painters and sculptors derive not only from their knowledge of drawing, the beauty of the colours they use or the value of the materials, but also from the grandeur of their ideas and from their perfect knowledge of whatever they represent . . .

Thus, the artist who does perfect landscapes is superior to another who paints only fruit, flowers or shells. The artist who paints living animals deserves more respect than those who represent only still, lifeless subjects. And as the human figure is God’s most perfect work on earth, it is certainly the case that the artist who imitates God by painting human figures, is more outstanding by far than all the others. However, although it is a real achievement to make a human figure appear alive, and to give the appearance of movement to something which cannot move; it is still the case that an artist who paints only portraits has not yet achieved the greatest perfection of art and cannot aspire to the honour bestowed on the most learned of his colleagues. To achieve this, it is necessary to move on from the representation of a single figure to that of a group; to deal with historical and legendary subjects and to represent the great actions recounted by historians or the pleasing subjects treated by poets. And, in order to scale even greater heights, an artist must know how to conceal the virtues of great men and the most elevated mysteries beneath the veil of legendary tales and allegorical compositions. (Félibien 1669)

Figure 2 Nicolas Poussin, a seventeenth-century French artist working in Rome, produced what his friend André Félibien described as the highest class of painting. Poussin drew upon Classical as well as biblical themes to represent moral, philosophical, and emotional values in paintings carefully composed in appropriate stylistic modes. The Return from Egypt, painted about 1630, showed the child Jesus having a vision foretelling his crucifixion; the ferryman presumably alluded to Charon, who in Greek mythology carried souls across the river Styx, separating the living from the dead. (Dulwich Picture Gallery)

During the seventeenth century, such values became increasingly important to the wealthy elite who commissioned, purchased, and collected such works for private enjoyment and public display. Experts refined the skills to assess the artistic and hence the commercial value of paintings. In 1719, the English painter Jonathan Richardson published criteria “Shewing how to judge I. Of the Goodness of a Picture; II. Of the Hand of the Master; and III. Whether ’tis an Original, or a Copy.” He set out principles of content, composition, and style, and wrote on “the science of a connoisseur,” concerning the quality, authenticity, and value of artefacts treated as art.

By the eighteenth century, the European elite had identified the knowledge and skill to create beautiful, thought-provoking images as an art superior to the production of other artefacts and had established as disciplines the history of art (or at least of artists) and the connoisseurship of artistic value. Th e vague and flexible concept of art, from being a general description of creative skill, was now helping to distinguish the culture of the elite from its lower classes. In this sense, it proved both useful and resilient as Europeans gained more experience of other cultural traditions.

INDUSTRIAL AND INTELLECTUAL REVOLUTIONS

As Europeans prospered from the fruits of discovery—from the labor of Native and African slaves on Native American lands, and military and political control of the maritime trade around Africa to India, China, southeast Asia, and across the Pacific to the far side of America—so their own culture changed with the experience of increasing globalization. By the late eighteenth century, when they began to invest the wealth of the world in the development of their own manufacturing industries, Europeans were becoming convinced that they had surpassed the achievements of antiquity and were now in the forefront of human development, ready to take charge of the world, intellectually as well as politically. Th is was still subject to divine providence, of course, but there was a shift from acceptance of the divine received wisdom of the theologians to a “natural philosophy” investigating God’s work in a world of ever-widening horizons. Th ere were debates over the seventeenth-century philosophies of the French René Descartes, who used reasoning by deduction from divinely instituted general facts and first principles, and of the English Francis Bacon, who preferred reasoning inductively from facts established by empirical investigation, as adopted by the British philosophers John Locke and Isaac Newton. Philosophy contributed to the scientific developments that produced new industrial technologies. The industrial revolution of the second half of the eighteenth century was also the product of an intellectual revolution, still described as the “Enlightenment,” which opened Europeans’ eyes to the world as we now imagine it to be. Kim Sloan has characterized it as “a desire to re-examine and question received ideas and values and explore new ideas in new ways. Th rough an empirical methodology, guided by the light of reason, one could arrive at knowledge and universal truths, providing liberation from ignorance and superstition that in turn would lead to the progress, freedom and happiness of mankind” (2003:12).

Among these new intellectual developments were new attitudes to art. By the mid-eighteenth century, connoisseurship had become a serious historical methodology. Th en, in 1764, the German Joachim Winckelmann published a history of art that rejected Vasari’s focus on individual artists in favor of more general considerations of cultural history. Winckelmann identified certain stylistic qualities with phases in the rise and decline of civilizations, from Egyptian through Etruscan and Greek to Roman. Th is supposedly reflected the history of the human spirit as identified by Plato, with the greatest artistic achievements made under the conditions of liberty attributed to ancient Greece, which reflected the political aspirations of Enlightenment intellectuals.

At the same time, the definition of “the arts” was changing, producing what has become the idea of “art for art’s sake,” as Shelly Errington has explained:

The eighteenth century took the idea of framing [images] further than the literal frame by distinguishing art from craft and separating the fine arts into five types: painting, sculpture, architecture, music, and dance. . . . By the end of that century, then, all five “fine arts” became useless contemplatable objects and required the frame—whether a picture frame, a pedestal, or a stage—to function as a boundary between the piece of art and the world, setting off art from everyday life, from social context, and from mundane utility. Th e frame pronounces what it encloses to be not “real” life but something different from it, a representation of reality. Th us at the end of the eighteenth century and the first part of the nineteenth century, music and dance, which are activities, were turned into aesthetic objects by framing them (with stage or platform) and separating them from the audience, which then contemplated them as spectacles, as the art connoisseur contemplated the painting on the wall. (1998:83–84)

A refined concept of the arts did not diminish interest ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART I: WESTERN PERSPECTIVES

- PART II: CROSS-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVES

- PART III: ARTISTIC GLOBALIZATION

- Afterword

- References

- Index