- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Secret Cemetery

About this book

Burial sites have long been recognized as a way to understand past civilizations. Yet, the meanings of our present day cemeteries have been virtually ignored, even though they reveal much about our cultures. Exploring an extraordinarily diverse range of memorial practice - Greek Orthodox, Muslim, Jewish, Roman Catholic and Anglican, as well as the unchurched - The Secret Cemetery is an intriguing study of what these places of death mean to the living. Most of us experience cemeteries at a ritualized moment of loss. What we forget is that these are often places to which we return either as a general space in which to contemplate or as a specific site to be tended. These are also places where different communities can reinforce boundaries and even recreate a sense of homeland. Over time, ritual, artefact and place shape an intensely personal landscape of memory and mourning, a landscape more alive, more actively engaged with than many of the other places we inhabit.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Secret Cemetery by Doris Francis,Leonie Kellaher,Georgina Neophytou in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Social Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Studying the Living in Cementeries

This is her first garden. It’s a memorial garden. It is a place to visit her still, and have a chat. The garden is another way of keeping in touch. I come every week on Thursday since she died. To tidy up, trim, cut the grass, put fresh water in, change the flowers that others bring. I feel she’s still with me. I used to see her every day when she was living. I worked where she lived and I would see her and have a cup of tea and a chat. Although Mum’s no longer alive, I still have a chat – for five minutes after I tidy up; I tell her what’s going on.

Thirty-eight-year-old East End resident whose mother had died two years previously and was buried at the

City of London Cemetery

This book, a study of what people do when they visit cemeteries, began with Class 29 at London’s Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, where one of us – Doris Francis – was studying landscape design in the School of Horticulture in 1995. The instructors gave the class an assignment: prepare a planting plan for an older cemetery in the English Midlands that was sponsoring a national competition to refurbish its grounds. When the students reviewed the site, they found no visitors tending graves, and none was invited to speak with the class about visitors’ needs and wants. When Francis told Leonie Kellaher, a fellow anthropologist and social gerontologist, about the assignment, they agreed that they wished to know more about what English mourners did when they went to cemeteries – about their activities, purposes and reflections.

Many scholars had previously studied burial sites, funeral rituals and mortuary behaviour among non-Western people, but few had made similar studies in their own contemporary Western industrial societies.1 Furthermore, books on English gravestones and cemetery design existed, but none was written from the perspective of those who used cemeteries.2 Here was new, useful research that needed to be done; as anthropologists, we would do our fieldwork at home, in England, in order to understand the cemetery experience from the viewpoint of the bereaved and to make our findings available to a wide public and professional audience. Although nearly every adult in London had some familiarity with cemeteries and what went on in them, these gardenlike places remained at once very public and very secret. We would study the unique culture that existed behind the cemetery gates to try to better understand these special spaces.

In 1996, the two of us – along with our sociologist colleague Georgina Neophytou – began to study London cemetery behaviour. We cautiously approached people and asked whether they would be willing to talk about why they visited the cemetery, what they did during their visits and what the visits meant to them.

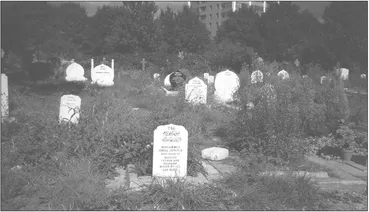

Most people, we discovered, were willing to talk to us. We interviewed and observed the actions of long-time English residents of the East End at the City of London Cemetery, where a well-kept, post– Second World War ‘lawn section’, featuring straight rows of graves with stone markers and small gardens (Fig. 1.1), adjoins older Victorian areas of elaborate monuments and tree-lined avenues. For comparison with other religious and ethnic groups, we talked to Orthodox Jews at Bushey United Jewish Cemetery, where grounds landscaped with ornamental pools, trees and flowers surround more austere, unplanted burial areas with expanses of white marble stones marking graves in long rows (Fig. 1.2). At New Southgate Cemetery, we spoke with the families of Greek Orthodox immigrants from Cyprus, who have turned sections of the 150-year-old cemetery into an exuberant garden by surrounding large white memorials with carnations, roses and plantings of rosemary and miniature cypress trees (Fig. 1.3).3 To extend our cross-cultural sample to London’s Muslim population, we interviewed Bangladeshi and Gujarati immigrants at Woodgrange Park Cemetery, where new Muslim graves were located in small clearings amid the thick overgrowth that covered older Christian memorials (Fig. 1.4) and where broken headstones lay gathered into piles near the derelict Gothic chapel. Behind the gates, each site seemed to hold its own secrets.

Figure 1.1. The lawn section of the City of London Cemetery, with its small grave gardens, 1998.

As the three of us crossed these cemetery thresholds, we entered a space ‘set aside’,4 a world that most people perceive as distinct from the everyday. As mourners themselves explained: ‘When you go through the cemetery gate, it’s another world.’ What we discovered there was that for the bereaved who visit cemeteries, these burial grounds are special, sacred spaces of personal, emotional and spiritual reclamation where the shattered self can be ‘put back in place’. Many mourners reported a sense of satisfaction, almost of sufficiency, at the end of a visit. They told of a charge of unrest that built up between visits and could be managed only through a return visit to the grave. Many actively resisted the push of the outside world to ‘move on’ and rejected the frequently asked question, ‘Why go to the cemetery, there’s nothing there?’ Many cemetery visitors relied on their own resources and the support of friends and family; they gave themselves time to mourn without self-judgement and measured their present ability to cope against the standard of the self two or three years earlier. Few allowed themselves to sink into total despair and monitored the amount of pain they could endure. Mourners reflected upon their own experiences to challenge popular homilies: ‘Time doesn’t really heal, but it does help to make the loss more bearable.’

Figure 1.2. White marble graves at Bushey United Jewish Cemetery, 1997.

The words, actions and reflections of these people also revealed the ways many of them used the resources of nature – the cemetery landscape and the flowers and plants they brought to the grave – and how they employed images of the grave as ‘home’ to put ‘flesh’ back on the bones of the deceased, to remember them and not to forget. Many users of City of London and New Southgate Cemeteries took part in a cemetery culture of gardeners whose embellishments of the grave with plants and flowers helped them to cope with grief, to keep the deceased’s identity alive and to regenerate their relationships even after death. The observations and reflections of all these study participants revealed something of the public yet hidden and secret cemetery as a place that connects the world of the living with the world of life after death.

To think about a grave and its cemetery as being like a garden appeared to help many mourners make sense of the incomprehensibility of death and the experience of loss. Although the rural churchyard has historically dominated the English popular imagination

Figure 1.3. Orthodox Greek Cypriot graves surrounded by roses, carnations and miniature cypress trees at New Southgate Cemetery, 1998.

and iconography of death, the bereaved in our research study chose instead to call upon the image of the garden when speaking about death and burial.5 It was the spiritual and regenerative aspect of the garden that seemed to inform this association between cemeteries and gardens, drawing on deep religious and historical roots. The imagery of paradise and the Garden of Eden in the Jewish, Christian and Islamic traditions, for example, suggested a beautiful, secluded park, ornamented with water, trees and flowers.6 Enclosed within this walled garden was the sacred tree of life; it was a place without death. In the teachings of Christianity, the garden remains religiously significant – a reminder both of the Garden of Eden and Christ’s agony at Gethsemane.7 As Adam was required to ‘dress and keep’ the sacred space of Eden before the Fall, so, too, the cultivation of the soil (and possibly the tending of a grave) became work ordained by God, and horticulture and burial in a garden offered a promise of paradise regained.8 Throughout English history, the enclosed garden has been seen as engendering repose and promoting harmony, its flowers and trees emblematic of spiritual truths, beauty and order. As an outdoor cloister, the garden has also been depicted as a religious house, offering retreat for spiritual and moral reflection, solitary meditation and communion with nature.9 Perhaps it was this ideal of the garden as a spiritual and palliative resource that led to its being privileged as an ideal accompaniment for burial.

Figure 1.4. New Muslim graves at Woodgrange Park Cemetery, 2002.

As a place of contemplation, however, the English garden with its fading flowers also confronts people with the transitoriness of life, the certainty of death and the vanity of earthly pursuits – even while the cycles of decay and renovation of nature offer consolation and solace.10 But in what other ways does the image of the garden inform mourners’ understanding of the cemetery? Both cemeteries and gardens are bounded places set apart from the rigid regularity of daily schedules and calendars; they are ‘timeless’ spaces of generational and accumulated time. Nature’s powers of rebirth and regeneration, as experienced in gardens and cemeteries, offer resources that confound and obscure an irreversible linear vision of the human life course and suggest, instead, a cyclical, repetitive and eternal view of existence that holds hope for immortality. Through the creation of the cemetery in the form of a landscaped garden, a harmony with nature was sought in death – a return to the lost Garden of Eden.

By entering the contemporary cemetery and viewing that world from the perspectives of the bereaved, we learned that while many mourners identified the cemetery with a garden, they also associated the ideas of home and tomb as another resource for dealing with death and loss. Dictionaries indicate an analogy between tomb and home (‘one’s abode after death’;11 and the ‘last’ home12) and many bereaved align these meanings when speaking about the grave plot and its marker.

Since ancient times, the architecture of the grave has mirrored society’s thoughts about the dwellings of the living.13 In writing about tombs as houses for the dead, the archaeologist Ian Hodder found that tombs in prehistoric Europe corresponded in shape, construction, orientation, position of entrance and decoration to houses of the same period.14 The tomb has also reflected a culture’s ideas about death and the afterlife.15 The ancient Egyptians, for example, believed that the dead lived on in the after-world. The tombs of the elites replicated the houses the deceased had enjoyed while alive and were intentionally built with rooms, corridors and false doors and windows, thereby extending the home boundary into eternity.16 The ancient Greeks, with a different view of the afterlife, feared death, and their gravestones often depicted and evoked the yearned-for humble home occupied in this life.17 From the Middle Ages onward, the Christian tomb, often located in the churchyard or church nave, represented a sleeping place from which death would be overcome at resurrection.

In ancient Mediterranean societies, as well as among some traditional cultures in Africa and the South Pacific such as the Tikopia of the Solomon Islands studied some seventy-five years ago by Raymond Firth, the custom was to bury the senior men of the household under the floor of the residential dwelling.18 This choice of burial location reflected the roles the deceased had played in life as well as those expected of them in death,19 and so acknowledged their ongoing participation in the life of the family and community. The dead were believed to influence the lives of their surviving kin, and their spirits were regular...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword: The Body in the Sacred Garden

- Chapter 1 Studying the Living in Cemeteries

- Chapter 2 The Dynamics of Cemetery Landscapes

- Chapter 3 Planting the Memory: The Cemetery in the First Year of Mourning

- Chapter 4 The Grave as Home and Garden

- Chapter 5 Negotiating Memory: Remembering the Dead for the Long Term

- Chapter 6 Keeping Kin and Kinship Alive

- Chapter 7 Cemeteries as Ethnic Homelands

- Chapter 8 Change and Renewal in Historic Cemeteries

- Appendices

- Notes

- References

- Index