- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Six Names of Beauty

About this book

Beauty may be in the eye of the beholder, but it's also in the language we use and everywhere in the world around us. In this elegant, witty, and ultimately profound meditation on what is beautiful, Crispin Sartwell begins with six words from six different cultures - ancient Greek's 'to kalon', the Japanese idea of 'wabi-sabi', Hebrew's 'yapha', the Navajo concept 'hozho', Sanskrit 'sundara', and our own English-language 'beauty'.

Each word becomes a door onto another way of thinking about, and looking at, what is beautiful in the world, and in our lives. In Sartwell's hands these six names of beauty - and there could be thousands more - are revealed as simple and profound ideas about our world and our selves.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Six Names of Beauty by Crispin Sartwell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Aesthetics in Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Beauty

English, the object of longing

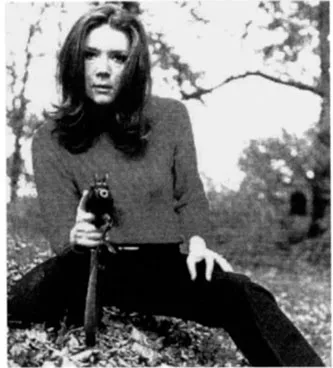

My first crush was directed not at a girl in my class or my neighborhood but, as is frequently the case in the era of mass media, at an image on my television screen. “The Avengers” was a British show, half spy adventure, half surrealist cinema. The lead female character, foil to John Steed’s unflappable bowler-topped gentleman, was Mrs. Emma Peel, played by Diana Rigg. There seemed to be no Mr. Peel in the picture to interrupt the accessibility of the magnificent Mrs. Peel. She often wore skin-tight leather jumpsuits a la Catwoman (I also had a certain affection for Julie Newmar in the latter role), and she moved around the English countryside with a grace usually reserved for professional dancers. And she absolutely kicked ass; she was an early example of the feisty, self-sufficient, potentially violent heroines who are now a staple of everything from Disney animations to high literature. She met every dilemma with perfect composure and deep wit. And of course Diana Rigg was beautiful, all cheekbones and slim curves.

At twelve I believed I was in love with her, and I pictured us together—not having sex, but just talking and perhaps sharing a chaste kiss. I read Diana Rigg’s personality from her performance, and fantasized that if she knew me, she’d love me, too. But it was safe to want her, because ultimately she was entirely inaccessible (and people who don’t realize that about their celebrity crushes mutate into stalkers). With a girl in my class, I might have had to express myself. With Mrs. Peel I didn’t have to, and thus I could invent long conversations with her to be held as we walked hand in hand. I imagined helping her defeat evil, then enjoying a relaxing evening with her at home. Erotic longing of this kind leads to intense experiences of beauty, and I certainly had them.

Diana Rigg remains forever young on the reruns, videotapes, and DVDs of “The Avengers,” but, of course, in life, many of the aspects of her loveliness and of my desire were fleeting. The fleetingness of youth and its particular variety of beauty provide a great theme of poetry and of life. Thus the poets advise virgins to make much of time. Diana Rigg ripened, and when next I saw her, twenty years later, hosting Mystery, she was still desirable, but in a different way. Her eyes still emitted that flash of wit; it had deepened into intelligence, and her charm into character. But I hate to say it: I felt loss.

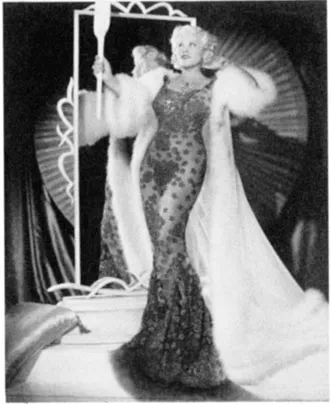

The relation of beauty to time and to loss is fraught with all of our feelings and ideas—and our repression of our feelings and ideas—concerning life and death. It must be very difficult for someone like Diana Rigg to age, and I congratulate her for doing so gracefully. But for “celebrities” or “sex symbols” to maintain unsullied their status as objects of desire they have to die young. James Dean, Marilyn Monroe; the great beautiful dead of rock ‘n’ roll: Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Kurt Cobain. Some beautiful people (Monroe) kill themselves. Some (Mick Jagger, Jane Fonda) try to maintain themselves in a semblance of youth. Some finally relax into their age. But of course in the long run whatever they and we have—youth, beauty, love, possessions—we lose.

****

The English word “beauty” derives from Old French “bealte” and eventually from the Latin “bellum.” In its earliest uses in written English, dating from the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, it refers almost exclusively to women, and that is still probably the word’s most common application, certainly when the term is used as a noun. That is not surprising. We may assume that much of the early writing in English was done by men who liked women, for whom the women they called beautiful were the objects of perhaps their most intense desire. And through the history of Western art, the female nude is the most frequent subject, with the exceptions of Jesus and Mary. Many of its greatest masterpieces directly appeal to erotic desire, from Titian’s “Venus and Cupid,” and Velasquez’s “Rokeby Venus,” to Georgia O’Keeffe’s flowers and Andy Warhol’s obsessively repeated Marilyns. And though usually art that is called “erotic” represents some kind of direct expression of sexuality, the erotic plays much more widely in the entire arena of human desire. In that sense, art that depicts the powerful might express the desire for power; art that depicts Jesus might express spiritual seeking; art that depicts food might express an appreciation of the pleasures of dining; art that depicts nature might express a yearning toward the world.

Though “beauty” has been defined very frequently and variously, it is also famous as a word that should not be, and perhaps that cannot be, defined. Nevertheless, beauty is the object of longing. I am less concerned to defend that as a definition than to use it as a basis for trying to find something common to certain kinds of human experiences and relations to things. Longing itself is an enduring, which is also to say unsated, state of desire. So in the broadest sense, the experience of beauty is always erotic, is always a wanting. Since we all long, beauty is a universal object of human experience. But to the extent that different epochs, cultures, groups, or individuals have different longings, their experiences of beauty will have different objects.

****

The philosopher and art critic Arthur Danto asks a simple question: why do we bring flowers to a funeral? What is the association of beauty with death, or with grieving? Perhaps, he says, we need a contrast to our grief, a small pleasure in the face of an overwhelming pain, a surcease from mourning that yields a kind of distance or perspective. But the relation of beauty to pain and in particular to loss is deeper and closer than that, I think. Beauty always bears within it the poignancy of loss, and the cut flower is not only an occasion of visual pleasure, but a symbol of what passes.

The loss that lingers in every beautiful thing intensifies desire. Indeed if we did not age, if things did not disintegrate, the experience of beauty would be impossible. Without loss, desire could be fulfilled at will; things would exist for us as perfect resources, always potentially available for our use. That we can lose things, that in fact we are always in the process of losing everything we have, underlies the longing with which we inhabit the world. And in that longing resides the possibility of beauty. The flowers and the music at a funeral are meant to make grief more poignant, to bring everyone into full participation with the grief, by including in it the touch of beauty. There is always a doubleness or an irony for us in the vitality of the cut flower. But grief and death and beauty call on us to yearn, and perhaps they call on us to yearn impossibly, to yearn for an object that is always slipping from our grasp.

****

The variety of the objects of beauty has been used as an argument for beauty’s subjectivity. As a matter of fact, we really cannot find some intrinsic quality that is shared by all things that people find beautiful. But our longing for these things does not make them beautiful. The claim that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” is false because beauty is a feature of the situation that includes the beholder and the object, the situation in which longing is made that in turn makes us move or cry or love or come. The beautiful thing is not the retinal image of the sunset or the firing of neurons in the brain in response to that image, or even exactly the transport of the soul that is induced. We experience the beauty of the sunset itself. We give beauty to objects and they give beauty to us; beauty is something that we make in cooperation with the world.

****

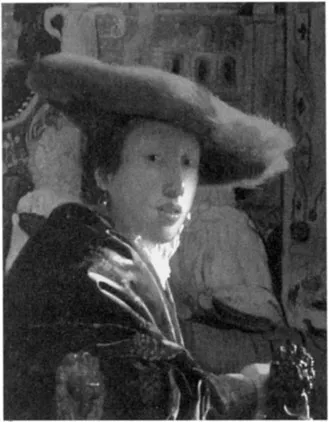

Shortly after contracting my crush on Mrs. Peel, I had my first profound experience of art. I grew up in Washington, D.C., with my parents dragging me to the National Gallery and other museums from the time I was a small child. Probably I oohed politely, but truly I regarded the works of art with an indifference appropriate to their status as monuments, things immune to childish regard. But one day, for reasons that remain obscure to me, I took a bus downtown and parked myself in the Dutch section. I was a little more interested by the paintings than I had been before, perhaps in part because I was following my own impulse by being there, and in gravitating to the seventeenth century and away from the Impressionists favored by my parents. I stared for some time at Vermeer’s tiny miracle, “Woman in a Red Hat,” a painting both respectful of visual reality and buffed smooth by light in Vermeer’s characteristic way. Several times I made up my mind to leave, then returned. Finally I had a feeling like falling, an almost romantic aesthetic swoon. It shocked me: I hadn’t thought myself capable of such a feeling. That experience motivated years of devotion to figuring out what art is and where that experience came from; it drives me forward still as I write this book. And though my feeling was deep, it was the painting, not the feeling that I loved, that possessed beauty. “Woman in a Red Hat” and I made that swoon together.

****

The classic triad of ultimate values is truth, goodness, and beauty. Truth is built into belief: to believe something is to take it to be true. Goodness is built into decision: to decide on a course of action (at least according to many thinkers) is to decide that it is best. And beauty is built into desire: what we desire we learn to find beautiful.

****

My stepfather was an amateur carpenter and cabinetmaker. A Quaker, pacifist, and political radical, he was a conscientious objector in World War II. While working in a lumber camp where objectors labored in the Pacific Northwest, Richard contracted polio. He spent a year in an iron lung and emerged a paraplegic. He never moved very far again without the use of artifacts or tools: crutches, wheelchairs, specially adapted cars and electric vehicles. For that reason and also due to something intrinsic, he had an unusual relation to the artifactual environment. I never really understood the use or the aesthetic of tools until he came to live with us when I was 12.

A couple of years later, we built a system of cabinets for tools and implements behind our house on Livingston Street. He taught me the use of the circular saw and other power tools, and in doing so he continually slowed me down and showed me how and why to work with care and to work in harmony with the tool. But even more than with the power tools, I was struck by the way he held and applied a hammer and the other simplest hand tools. He had great precision but also strength: he worked with care and decision. Each stroke of a hammer cost him a great effort, and so he made each stroke count, his weathered hand directing the tool with a concentration that merged eye, hand, and tool into a single system. Richard was never a connoisseur of tools in the sense of collecting them for their own sake or buying expensive things; the hammer I remember best from 1970 was the simplest possible, with a somewhat rusty head and a plain wooden handle. He still had that hammer when he died in 2002; I have it now.

****

Ananda Coomaraswamy, the early twentieth-century Indian aesthetician and museum curator, said that “a cathedral is not as such more beautiful than an airplane, … a hymn than a mathematical equation; … a well-made sword is not more beautiful than a well-made scalpel, though one is used to slay, the other to heal. Works of art are only … beautiful or ugly in themselves, to the extent that they are or are not well and truly made, that is … do or do not serve their purpose.” The definition of beauty as suitedness to use is wrong, I think. Sometimes beauty shows wild excess to any possible use, and though a simple sword that is perfect for killing may be beautiful, so may be a fantastical blade that is suited for little but to be looked at. But Coomaraswamy’s definition also contains an important insight. We are surrounded by a world of artifacts designed to bring our desires to fruition. If these things are made truly and well, we experience them—whether they are buildings, pieces of furniture, vessels, or tools—as beautiful, because they help us realize our desires in a satisfactory way. They take up a place in the economy of our longings. Indeed, few objects are so simply and obviously beautiful as a well-made tool, the purpose of which is by necessity inscribed in its design, and craftsmen devote themselves not only to making the objects of their craft, but to an appreciation of tools, a love of the means by which they achieve their ends. In craft, means and ends become intertwined so that the process itself by which the crafted object is made is experienced as an end: the process itself is beautiful, like a dance. An excellent craftsman, at work on a pot or a cabinet, engages in a beautiful process that eventuates in a beautiful and useful object. The tool both expresses a desire and leads toward its satisfaction, and to that extent can itself be the object of longing.

****

Plato, in the Symposium, made the key connection of beauty to eros, desire. He believed that worldly beauty, especially the beauty of sexually attractive people, could bring us toward a supernal beauty, a beauty that would consist of the purest, most abstract truth. Be that as it may, we cannot ignore the use of the term “beauty” to refer to the arts of makeup and coiffure: the whole arsenal of techniques supposed to render one desirable. The most widely appreciated “beauties” are models and movie stars.

The history of cosmetics testifies to human ingenuity, to what can be accomplished by squads of technicians operating on overlapping generations for millennia, creating objects of yearning from Nefertiti to Lucretia Borgia to Mary Pickford to Lauren Bacall to Jennifer Lopez. Cosmetic artists, in fact, talk about “creating a face” on a human armature, and it is amazing how elaborate or even dangerous and bizarre the process of creating a face can be. Consider this list of ingredients in medieval makeup: “arsenic sulfide, quick lime, bat blood, bees’ wings, mercury, and slug slime for waxing, polishing, and whitening; decoctions of green lizards in walnut oil, sulfur, and rhubarb for bleaching.” An alchemical potion for eternal beauty recommends distilling young ravens and drinking off the product, a process that must have presented certain difficulties. The British parliament considered a law in the eighteenth century declaring cosmetics, perfumes, and artificial teeth to be witchcraft, to which, as the preceding formulae show, they were indeed closely related.

The witchcraft of cosmetics always idealizes the body, smoothes over its singularities and idiosyncrasies in order to make of it an ideal object of desire. The beauty of Jennifer Lopez is supposed to be universal, a general representation of femininity, a kind of skinniest common denominator of nubile womanhood. It is universal also in the sense that it is normative for sexuality: it is supposed to display what all men want and what all women want to be.

But if Plato thought that beauty pursued truth, the beauty industry argues against him. Beauty in the sense of cosmetics and coiffure devotes itself to artifice (its “falsity” again connects it to witchcraft), concealment, disguise, to manufacturing appearances. Beauty as the beautician understands it is not the reality underlying the appearance; it is the apotheosis of appearance. Oscar Wilde claimed that beauty is sheer surface, that what’s good about it is that it’s only skin deep, or not even skin deep. In the world of cosmetics and high fashion, the terms “nature” and “natural” appear continually and uncritically, but always “nature” is itself an artifice: “natural” refers to the style of Chanel in contrast with that of Dior, for example.

We long toward the unattainable beauty of the human face or the human body perfected, smoothed over into a kind of screen onto which we project our desires. Even the perfect people depicted in films and magazines are not as perfect as their depiction, and there is art in making the images themselves impossibly beautiful. The perfection of the pinup, model, and movie star as sexual objects is completed by the fact that they are already lost to us, lost to us in the process of fantastic idealization even before we can attempt to attain them. In this way, they are ideal objects of longing.

****

We also appreciate a seemingly opposite beauty: beauty of character, of saints and sages, or of people with more simplicity, serenity, or clarity than we ourselves possess. Though beauty seems to be a concept of perception—clearly connected to the visual, auditory, gustatory—so that something as elusive to sense as a “soul” or personality could not be beautiful, the conception of the beautiful soul or personality is quite familiar and is sensible to the extent that we understand perfectly well what is meant. It is in part a moral notion, and there is no profit, finally, in trying to keep moral and aesthetic ideas wholly insulated from one another—though certain strands of philosophy have tried to do just that—because morality, too, plays in the arena of human desire, though with different implications.

There are two modes of the erotic: what we desire to have (or make love to, or give love to), and what we desire to be (what we aspire to, what we emulate). We experience both of these in popular entertainments such as novels or (especially) film and television, where glamour of character can have either effect or both simultaneously. If we c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- 1. BeautyEnglish, the object of longing

- 2. YaphaHebrew, glow, bloom

- 3. SundaraSanskrit, holiness

- 4. To KalonGreek, idea, ideal

- 5. Wabi-SabiJapanese, humility, imperfection

- 6. HozhoNavajo, health, harmony

- Notes

- Illustrations

- Index