eBook - ePub

Available until 4 Dec |Learn more

The Family and the School

A Joint Systems Aproach to Problems with Children

This book is available to read until 4th December, 2025

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 4 Dec |Learn more

The Family and the School

A Joint Systems Aproach to Problems with Children

About this book

This edition has been revised and updated to include more material specifically related to work with schools. It reflects the major changes in society, in legislation and in the nature of the interaction between families and the education system in the last decade. The contributors all have links with the Child and Family Department of the Tavistock Clinic and include educational psychologists working with schools and hospitals, family therapists, child and family psychiatrists and teachers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Family and the School by Emilia Dowling,Elsie Osborne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

A joint systems approach to educational problems with children

Emilia Dowling

Most professionals in the mental health field would recognize that two of the most influential systems in an individual’s development are the family and the school. However, not enough has been done to bring these two systems together as part of a therapeutic strategy to deal with problems in children.

Since the first edition of this book there have been interesting developments in the social context in which families and schools function. New legislation affecting these two systems will no doubt have far-reaching effects on children’s development in the family and school context in years to come. On the one hand the law has highlighted and recognized the children’s needs and rights. On the other hand, the current economic climate has prevented the expansion of children’s services and the danger is that these services will be required to focus mainly on ‘statutory’ work, making the scope for preventive and consultative work increasingly difficult.

In the face of an enormous amount of imposed change, the education system has to continue providing an environment for children to learn. Families in recent years have undergone increasing changes in life patterns and styles. In this changing environment the relationship between families and schools continues to evolve with children as linchpins between these two systems. Continuing efforts to develop work which meaningfully addresses this dual context are described in the second edition of this book.

The aim of this chapter is to examine the concepts of general systems theory as they apply to family and school functioning, with particular reference to the interaction between them when problems of an educational nature arise with children. The relationship between family and school systems, the meaning of organizational culture and beliefs and the implications for therapeutic interventions when problems occur in this dual context, are discussed.

Since the early 1960s clinicians have learned to put the individual in the context of the family, and this has led to the development of family therapy as a therapeutic alternative to individual treatment. Educationists have also moved from the belief that all problems reside within the individual to consider how pupils’ behaviour is affected by the particular educational establishment of which they are part (Burden, 1981a, 1981b; Gillham, 1978, 1981; Rutter et al., 1979). However, the applications of systems notions to families and to schools have developed quite slowly and separately and the result is two rather divorced schools of thought and practice, with insufficient cross-fertilization between them. On the one hand, there is a wealth of family therapy literature, and on the other, the educational literature, emphasizing school systems interventions.

Since Aponte’s seminal paper (1976) advocating the family-school interview, attempts have been made to explore children’s problems in the dual context of family and school although not all of them approach the subject from a systems perspective. Tucker and Dyson (1976) described an ongoing project involving families and school staff which, in their view, brought about changes in traditional practices for school psychologists as well as better communication between the two systems. Love and Kaswan (1974) examined the family and school environment of elementary school children from a wide range of socio-economic areas in order to ‘identify characteristics of family and school environments that seemed related to children’s personal social effectiveness’. Fine and Holt (1983) have examined implications of a family systems approach for school-based consultants. They warn of the problems of identifying the ‘client system’ and of the complexities of selecting appropriate strategies for both systems. S. Holmes (1982) outlines a series of useful steps in dealing with learning difficulties in a social educational context.

Studies of a more sociological, rather than interventive, nature include those by Craft et al. (1980) and Johnson (1982).

In Britain, Taylor (1982) has described a model of family consultation in a school setting. She has also highlighted the dilemmas for the child as the family and school ‘go-between’, having to negotiate daily the transitions from home to school (Taylor 1986). Recently Cooper and Upton (1990) have described an ecosystemic approach to emotional and behavioural difficulties in schools which seems particularly valuable for teachers. Frederickson (1990) has re-evaluated the systems approaches in educational psychology practice. She advocates the use of soft systems methodology and refers to its application to the school context.

Stoker (1992) looks at the forces militating against change in the role and practice of educational psychologists. He perceptively examines the strongly held belief by many families, schools and education officials ‘that children can be “treated” and changed without any undue interference with the social system of which the child is a part’. He suggests that to challenge such a belief is to challenge a very entrenched power structure which will not readily welcome change. He alerts educational psychologists to be aware of these dynamics and proposes three models of service delivery which might help to address the issues and be of interest to educational psychologists wishing to effect systemic change.

Although the literature on the subject is scarce, in recent years an increasing number of practitioners recognize the importance of viewing families and schools as open systems in constant interrelationship with each other. The contributions to this book reflect some of the developments in this field.

A SYSTEMS PERSPECTIVE

A systems way of thinking refers to a view of individual behaviour which takes account of the context in which it occurs. Accordingly, the behaviour of one component of the system is seen as affecting, and being affected by, the behaviour of others. Ackoff (1960) defines a system as ‘any entity, conceptual or physical which consists of interdependent parts’. However, it is important to remember that systems theory stems from the physical sciences, which are more exact and predictable than the social sciences. The boundaries around physical systems are more clearly defined than those in social systems, where they are often arbitrarily determined.

General systems theory, which was conceived by von Bertalanffy (1950), provides an alternative theoretical framework to the linear model, which looks for causes in order to explain effects. Most professional trainings are based on a linear model, and in fact the mental health professions have been influenced by the traditional medical model in their search for the aetiology of pathological phenomena in dealing with emotional problems. The traditional scientific method by which variables are isolated in order to test out whether they cause a particular phenomenon is another example of how well-trained minds depend on linear thinking.

Plas, in her book Systems Psychology in the Schools (1986), offers a very thorough review of the theoretical and philosophical basis for systemic theory. Her work is particularly important as it refers in detail to some crucial precedents to the development of systems ideas: for example, Gestalt theory (Kofka, 1935), field theory (Lewin, 1952), and transactional theory, in particular the influence of Dewey and Bentley (1949), whose work was concerned with the relationship between the observer and the observed. This notion is, of course, central to the systemic epistemology, which holds that what we know depends on how we know (Keeney, 1983).

The application of Plas’s ideas to work with school systems is explored further in Chapter 2.

KEY CONCEPTS OF GENERAL SYSTEMS THEORY

Context

One of the basic tenets of general systems theory is the emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs:

Living systems, whether biological organisms or social organizations are acutely dependent upon their external environment and so must be conceived of as open systems … open systems [which] maintain themselves through constant commerce with their environment, i.e. a continuous inflow and outflow of energy through permeable boundaries.(Katz and Kahn, 1969, p. 91)

In terms of social processes this means a move from the intrapsychic to the interpersonal level, from an individual to an interactional view of behaviour. This conceptual shift in the social sciences has taken place in parallel with developments in the physical sciences, where the focus has also moved away from a concern with the intrinsic properties of the matter to the way in which the matter is organized and the ways its particles relate to one another.

Circular causality

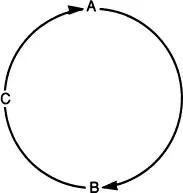

If we view behaviour in terms of cycles of interaction, instead of asking whether A causes B, the behaviour of A is seen as affecting and being affected by B and C, as shown in Figure 1.1.

When families find themselves locked in dysfunctional interaction patterns, a linear explanation of the ‘cause’ of the problem is not very helpful as it just swings the blame from one person to the other. In the case of a mother who complains about her husband’s lack of involvement in the care of their child, it is more useful to identify the sequences of interaction which contribute to the perpetuation of the problem, than to apportion blame for it. The sequence can be translated as follows: the more she tells him that he never helps, the less he will help, since he feels so incompetent next to her, the more she does not let him try, the less he can learn, and so it goes on, only escalating as the recriminations extend to other areas, and consequently further uninvolvement and discontent will be triggered. A similar cycle could be identified in a school where the head teacher, who behaved in an authoritarian and autocratic manner, complained about his staff not supporting or helping him; the more he made his own decisions – without consulting, as he thought he would not be supported – the more his decisions were perceived by the staff as impositions; therefore they felt infantalized, did not take part in the planning of events and, on occasions, even behaved like irresponsible adolescents.

This view of events implies a different epistemology; the question why (linear, cause-effect model), is replaced by how the phenomenon occurs, and attention is paid to the sequences of interaction and repetitive patterns which surround the event.

Psychological functioning involves a reciprocal interaction between behaviour and its controlling conditions, and as actions are regulated by their consequences, the environment is, in turn, altered by the behaviour (Bandura, 1969).

Plas suggests that the term recursive, identified by Bateson (1979), captures the essence of non-linearity. ‘A recursive phenomenon is the product of multidirectional feedback, which occurs as functional and arbitrarily identifiable parts of a system engaged in transaction across time and space. A recursion is non-linear; there is mutuality of influence’ (Plas, 1986, p. 62).

Punctuation

The notion of circularity is intimately linked with the concept of punctuation, that is, the point at which a sequence of events is interrupted to give it a certain meaning. If reality is viewed in terms of interactional cycles, it is easy to see how a certain interpretation of what causes what depends on the way reality is punctuated. ‘Every item of perception or behaviour may be stimulus or response or reinforcement according to how the total sequence of interaction is punctuated’ (Bateson, 1973, p. 263).

A secondary school requested that ‘something must be done’ with a boy who was described as severely disturbed. When teachers were asked for a specific example of how he behaved and what made him appear as severely disturbed, they referred to the fact that he punched a boy who accidentally knocked his lunch tray and spilt milk on his blazer. This was, the head of year said, the proof of how severely disturbed he was – a disproportionate reaction, as he saw it, to a relatively minor incident. The head had chosen to punctuate reality at the point of the boy’s behaviour, labelling it as disturbed. Exploration of the context revealed that the mother, a widow living on Social Security, had saved for a year to buy George a new blazer and had threatened to ‘beat the hell out of him’ if he damaged it. This was the first time George had been allowed to wear his blazer.

No punctuation is right or wrong – it just reflects a view of reality. Our particular view of reality is that behaviour is intimately dependent on the context in which it occurs. When educational problems arise, it is useful to examine the problem in the dual context of the family and the school.

Homeostasis

This term, first used by Walter Cannon (1939), refers to the tendency of living organisms towards a steady state of equilibrium. ‘Homeostasis is made possible by the use of information coming from the external environment in the form of feedback. Feedback triggers the system “regulator” which by altering the system’s internal condition maintains homeostasis’ (Walrond-Skinner, 1976).

However, the application of this essentially biological concept to the understanding of social systems has been challenged by family theorists such as Dell (1982) and Hoffman (1981), who prefer the notion of coherence. Hoffman defines ‘coherence’ as having to do with how pieces of the system fit together in a balance internal to itself and external to its environment.

Nevertheless, the self-regulating properties of the family system have proved a useful notion to clinicians in understanding the purpose of the present problems and the tendency in families to maintain the status quo and resist change. As Gorell Barnes points out,

Its value in clinical assessment is that it offers clinicians a way of thinking about key characteristics in the family which are interrelated with the present problem … It may also help him consider what the likely effects of improvement...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Notes on contributors

- Foreword to first edition

- Foreword to second edition

- Introduction

- 1 Theoretical Framework: A Joint Systems Approach to Educational Problems with Children

- 2 Some Implications of the Theoretical Framework: An Educational Psychologist’S Perspective

- 3 The Child, the Family and the School: An Interactional Perspective

- 4 Taking the Clinic to School: A Consultative Service for Parents, Children and Teachers

- 5 Joint Interventions with Teachers, Children and Parents in the School Setting

- 6 Parents and Children: Participants in Change

- 7 The Teacher’S View: Working with Teachers Out of the School Setting

- 8 Some Aspects of Consultation to Primary Schools

- 9 Schools as a Target for Change: Intervening in the School System

- 10 Consultation to School Subsystems by a Teacher

- 11 The Children Act 1989: Implications for the Family and the School

- 12 Issues for Training

- Bibliography

- Name index

- Subject index