1.1 Historical Background of the Problem

For centuries, the development of civilisation has been inextricably linked to the processes of microbial colonisation of the places and residences where humans live. The problem of the contamination of indoor environments, and the related phenomenon of biodeterioration of primary products, materials and buildings, has therefore accompanied humanity since the dawn of its history. Probably the oldest mention of the destructive effects of microbiota – referred to back then as red and green ‘leprosy’ – on rooms and clothing comes from the Book of Leviticus, the third book of the Pentateuch of the Old Testament. Both prehistoric times, as evidenced by analyses of cave paintings from the Paleolithic period, as well as events related to archaeological and conservation research, were associated with properties which were destructive for organic and inorganic materials – mainly mould and actinomycetes, exacerbated by the presence of water in the environment. It was in 23 BC that the famous Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, in his work de Architectura, made the observation that ‘the bedrooms, as well as the libraries, should be situated so as to face eastwards, as this prevents the spread of damp and helps to avoid the spread of mould on both rooms and books’. Among researchers of the modern era, the role of dampness as a factor responsible for indoor bio-corrosion and the associated adverse health effects was probably first highlighted by Iranian doctor Mohammed bin Zakariya Al-Razi (865–925 AD). He stated that ‘avoiding being in damp interiors prevents the sinus pain or rhinitis and reduces airborne infections’. Although the conclusions concerning the importance of water in biodeterioration processes were already formulated in ancient times, significant progress in counteracting the effects of water damage was inhibited until the Renaissance. It was only then that the use of milk of lime as a means of protecting the structural elements of buildings against mould was popularised in Europe by the builders of Italian cities situated by rivers or canals. It was then popularised by Spanish conquistadors in the New World at the end of the 15th century.

Although the biodeterioration of buildings and works of art has been observed since ancient times, and information on the damaging impact of micro-organisms can be found in various periods of history, it has long been believed that the dominant factors of material corrosion are chemical and physical processes, ignoring the importance of biological corrosion [Sterflinger and Piñar 2013]. In practice, only at the end of the 19th century were bacteria and fungi found to have the ability to colonise building materials which may then lose essential properties under their influence. A change in the approach to the problem of bio-corrosion was reflected in the practical measures taken in Europe at that time (mainly in Germany, Austria, Switzerland and France) in the field of so-called ‘building mycology’. The work of R. Hartig released in 1885 by the Berlin Springer publishing house, titled Die Zerstörungen des Bauholzesdurch Pilze. 1. Der ächte Hausschwamm (Merulius lacrymans Fr.), was the inspiration for many initiatives within this field. In Germany and Switzerland, scientific research began on the mechanisms of mould infestation of buildings, as well as the search for appropriate measures to control and prevent it. In 1898, a special committee on the control of household mould was established in Zurich, and seven years later, the German authorities set up a Government Advisory Committee for the Control of Household Mould, consisting of biologists, foresters and construction specialists. As a result of the above, the Institute for Household Mould Research in Wrocław, Poland, was established as a laboratory for scientific research aimed at determining the mechanisms of biological contamination of buildings. Its second director, R. Falck, together with J. Liese and the above-mentioned R. Hartig, created the scientific basis for present-day building mycology. The periods of the First and Second World Wars led to catastrophic destruction and degradation of many buildings, ranging from residential, public and industrial buildings to historic sites and museums. These buildings, overexploited and not renovated during both armed conflicts and the post-war periods, became sites of mass development of microbiological corrosion which led to their biodegradation. At that time, expertise in such degraded buildings was once again an area of interest for researchers, which led to the commercial-scale production of chemicals intended for both the protection of building timber and the removal of mould from walls. The 1930s and the period after the Second World War (1945–1966) led to the development of materials science which, within its field, dealt not only with expert evaluations of biologically corroded buildings, but also with the problems of protection against bio-corrosion. These included the development of methods for the assessment of material protection measures, together with instructions for their defence, and anti-mould protection of buildings [Karyś 2014; Ważny and Karyś 2001].

The processes of microbiological corrosion of materials are inevitable, and the problem of ‘sick buildings’ and its solution continues to be an important issue for modern science and technology. It requires the interdisciplinary involvement of many fields, combining theoretical and practical knowledge of biology with technical, technological and design methods. These issues are undoubtedly underpinned by a thorough understanding of the phenomenon of bio-corrosion, recognition of its causes and the development of effective ways to prevent it.

1.2 Contemporary Problems Related to Microbiological Contamination of the Indoor Environment

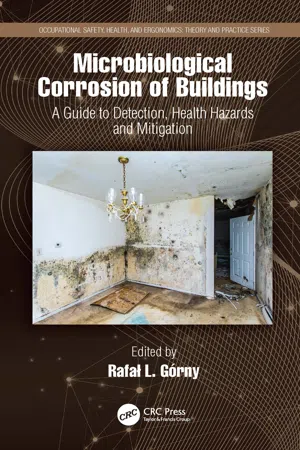

Buildings are continuously exposed to colonisation by micro-organisms present in the environment. During the exploitation of construction objects, their structural elements are subject to environmental stress caused by water in its various forms. Whenever water makes contact with the surface of a construction material, or seeps inside it, microbiological contamination may occur. Roofs, floors, lower walls or foundations are most often exposed to dampness and biodegradation. This type of damage is relatively common and is usually associated with mould, and the scale of this phenomenon is evidenced by numerous scientific works [Górny 2004; WHO 2009].

In recent decades, natural disasters caused by water have hit many regions of the world quite regularly. One of the biggest problems for victims of this type of disaster is the return to their homes and workstations. Buildings damaged by water are usually uninhabitable due to the condition of the structure, damage to various types of installations or sanitary conditions. The presence of water and the pollutants in it create ideal conditions for the development of micro-organisms that can threaten human health, either through direct contact with their source or indirectly through their emission into the air. According to U.S. statistics, almost all of its 119 million homes and 4.7 million public buildings have experienced an episode of severe dampness due to flooding, swamping or water intrusion into their interiors in their history [U.S. Census Bureau 2003]. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina led to a disastrous flood in New Orleans. Destroyed, and abandoned by many inhabitants, the city has become a place where both the ways of spreading microbiological pollutants and the methods of removing them from damp materials can be studied to this day [Adhikari et al. 2009; Chew et al. 2006; Farris et al. 2007; Rao et al. 2007].

Inevitable climate change is causing frequent floods around the world, and thus increasing the risk of water damage to various types of buildings, ranging from residential through public to agricultural and industrial facilities. According to the report published by the European Environment Agency, there were 3,563 floods in 37 European countries between 1980 and 2010. The highest number (321) was recorded in May and June 2010 in 27 Central European countries.

Many regions of the world were devastated by floods in 2019. According to FloodList data, 15,000 houses in India and 13,000 houses in Africa were affected by the floods that occurred in September 2019 alone. The losses incurred by the U.S. as a result of Hurricane Dorian and the floods it caused run into trillions of dollars. At the same time, torrential downpours also led to flooding and inundations in European countries [FloodList 2019]. Scientists predict that by 2050, the number of floods in the world, and the economic losses associated with them, will have increased five times, and by 2080, 17 times. This is due to global warming, increasing the value of land around flood plains and rapid urban development [EEA 2016]. It can therefore be assumed that, considering that number and scale, a long-term effect destroying microbiologically contaminated or damp buildings and potentially causing health problems may affect families whose dwellings did not undergo appropriate restoration and drying procedures, as well as appropriate anti-mould protection. The scale of this problem is also evidenced by the fact that the cost of damage to buildings caused by microbiological corrosion is estimated to exceed €200 million per year in Germany alone [Sedlbauer 2001]. According to Finnish data, the estimated unit cost of repairing microbiologically damaged interiors which had an adverse impact on the health of occupants may be as high as €10,000–€40,000 per year [Pirinen et al. 2005]. Nevertheless, the overall costs of removing the bio-corrosion from building construction are difficult to estimate. This is because they include not only the costs of cleaning, but also renovation and repair, and, in many cases, also the costs of destruction of cultural assets associated with the devastation of historic buildings [Gaylarde et al. 2003].

Undoubtedly, it can be stated that the problem of microbiological contamination of interiors is nowadays a worldwide phenomenon, and building materials are affected by biodeterioration regardless of the climate zone or location of the building [Ribas Silva 1996]. According to a survey carried out in North America, 27–36% of houses are affected by mould. According to research using measurements of indoor air quality, this proportion reaches even 42–56%. In European countries, the proportion of damp and mouldy residential buildings varies between 12–46% in the UK, 15–20% in the Netherlands and Belgium and 12–32% in the Nordic countries (Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Iceland and Estonia). Despite this, the proportion of signs of building damage caused by excessive dampness, as recognised by construction engineering specialists, can reach up to 80% of residential buildings. A similar situation is observed in the Middle East and in Asian countries. For example, in Israel as many as 45% of houses have problems with dampness and mould, while in 20% of the interiors these problems are considered serious. In the Gaza Strip and on the West Bank of the Jordan River, it was observed that in 56% of the houses the mould spread on walls and ceilings. In Ramallah it was found that this proportion is as high as 78%. It is also estimated that in agricultural areas of Taiwan 12% of homes are damp, 30% have signs of household mould, 43% have had water intrusion and in 60% of interiors at least one of the above-mentioned signs occurred. In Japan, almost 16% of houses show signs of mould [Adhikari et al. 2009; Chew et al. 2006; Farris et al. 2007; Rao et al. 2007].

The consequences of microbiological contamination of premises are, on the one hand, progressive corrosion of building materials and, on the other hand, a decrease in the quality of indoor air, resulting in the occurrence of ‘sick building syndrome’ (SBS) symptoms such as fatigue, headaches, dizziness, nausea, exhaustion or mucous membrane irritation [Sundell et al. 1994; Robertson 1988].

1.2.1 Traditional and Modern Building Materials

The comfort of the building and its resistance to biodeterioration depends largely on the building materials, what they are made of and their proper use. Despite significant progress in the construction sector, there is no clear methodology for implementing an appropriate selection of these materials [Fezzioui et al. 2014]. A...