I

Berber Society in the Maghreb and the Formation of the Sherifian Empire

Ibn Khaldun, the only Muslim historian to encompass within a single sweep the whole troubled history of Maghreb society through several centuries, formulates an hypothesis regarding the Berbers, in a famous passage in the Kitab al-ʽIbar,1 whose powerful insight we have not always recognised. “They belong”, he tells us, “to a powerful, formidable, brave and numerous people; a true people like so many others the world has seen—like the Arabs, the Persians, the Greeks and the Romans.” But the great writer immediately adds this rider, whose validity has not diminished since the fourteenth century: “Such was the Berber race. But, having fallen into decadence, and having lost their nationalistic spirit through the luxurious life that the exercise of power and the habit of domination had permitted to develop, their numbers decreased, their patriotic fervour diminished, and their corporate identity became weakened, to the point where the various peoples who made up the Berber race have now become the subject peoples of other rulers and bow like slaves under the burden of taxation.”

In fact, the Berbers are, even today, a great people, but the tribes which comprise ‘Barbary’, from western Egypt to Morocco and Senegal, are scattered throughout the different regions of North Africa, “like the membra disjecta of a nation” in the words of Ibn Khaldun. Nevertheless, they retain a common heritage of language, of thought and of primitive art intact in the midst of the Arab populations which separate them one from another; they retain the same fundamental basis of social and political organisation, as well as their own intellectual inclinations and emotional make-up. One can say further that they have retained a profoundly original form of collective life. On these grounds, then, they are still a “brave and numerous” and great people.

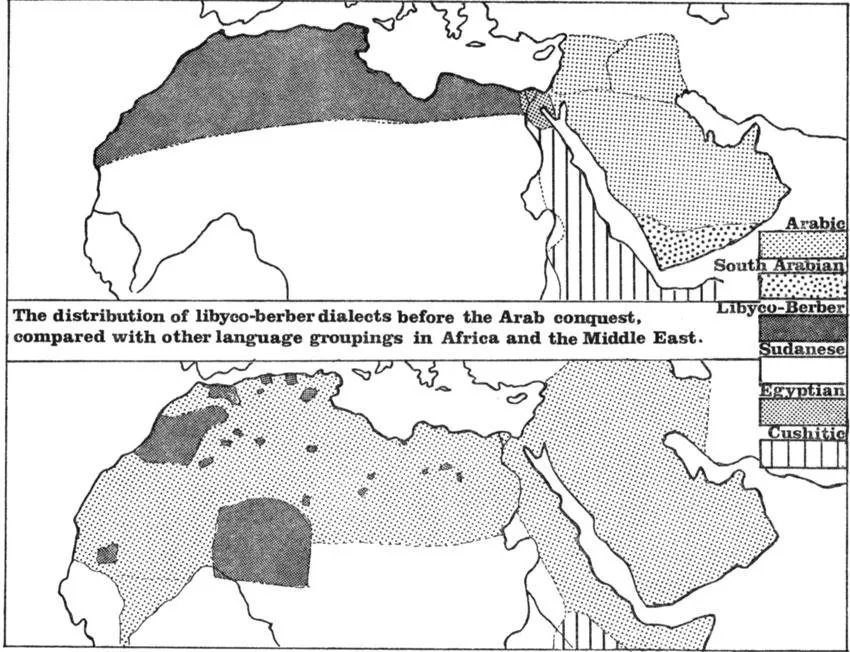

The region in which the Berber language was spoken has broken up and become highly fragmented over the centuries. The principal centres remaining of some significance today are to be found in Morocco and the Sahara. It is necessary to point out, however, that the latter concentration (constituted largely by the Tuareg group) is, despite its demonstrable size, much less important than the former because of its extremely low population density. The Arabic language has spread through the entire Arabian Peninsula and the whole of North Africa. Source: Meillet and Cohen: Les Longues du Monde.

But even if the Berbers have resisted the rising tide of Arab civilisation from their mountain fastnesses up until the present day, it is certainly true that the entire history of the Maghreb has been dominated, for more than a thousand years, by the same process: the slow destruction of indigenous institutions and the progressive assimilation of the indigenous African populations by Arab tribes and by Islamic civilisation. It is the political and social aspect of their struggle against these forces that we intend to explore in the following pages. We hope to demonstrate how Berber society has continued to show an indestructible vitality, even in our own century, and despite its decadence.

We shall be concerned initially to investigate and to describe what different linguistic, religious and political forms the attack on the Berber way of life took during the course of history, and our examples will be drawn repeatedly from that particular region of the Maghreb that we call today Morocco, for it is there that appear to be concentrated with the greatest energy and at the same time both the forces of destruction and the forces of renewal.

The Linguistic Distribution of the Berbers

Let us look now at the linguistic map of North Africa, for the retreat of Berber society can be demonstrated most clearly by means of the linguistic evidence. In this way we shall be able to judge at a glance the importance of the changes that have taken place since antiquity. Let us refer, for example, to the maps given in LesLangues du Monde, edited by Meillet and Cohen,2 which are more eloquent than a long historical narrative (see Map 1).

In the fifth century BC, before the Roman conquest, the Berber peoples—the Libyans, the ‘Getules’, and the ‘Troglodytes’ of whom Herodotus and Hanno write—were in contact throughout northern Africa with ‘Nigritia’, the country of the ‘Ethiopians’. Then, later, when they had become Romanised, or else had undergone the influence of the Carthaginians on the coast, they pushed the peaceful black populations of the oases back towards the southern regions of the Sahara. It was at about the time when the Berbers had thrust back and destroyed the ‘Ethiopians’ that the Arabs made their first appearance in the Maghreb. First of all, and indeed until the tenth century, they presented themselves only as political and religious leaders, and the language they spoke was spread only by the diffusion of the Islamic faith. Then, between the tenth and the fifteenth centuries, they became invaders and pushed towards the extreme west of the Maghreb in two waves: that of the Hilal, who came for the most part via the Tell, and that of the Maʽqil, who came up from the fringes of the desert.3 The results of these incursions by the Arabs may be seen on any twentieth-century map.

Today the Berbers have retained their language—the guardian of their traditions and of their laws—only in the mountains, in the oases of the Sahara, or in the inaccessible depths of the desert. The principal groupings are those of the Jebel Nefusa, of the Aures, of the Jurjura Kabylia, of the Rif, of the Western Atlas, of the Middle Atlas and of the Suss. The Zenaga, on the borders of Senegal, number only a few tens of thousands, while the Tuareg, despite the size of their territory, are only a few thousand. Almost everywhere the spread of the Arabic language is marked, if perhaps slow. Doutté and E. F. Gautier have estimated that in Algeria Arabic is gaining 40, 000 converts every fifty years. It is clear that at other periods in the past its progress has been more rapid still.

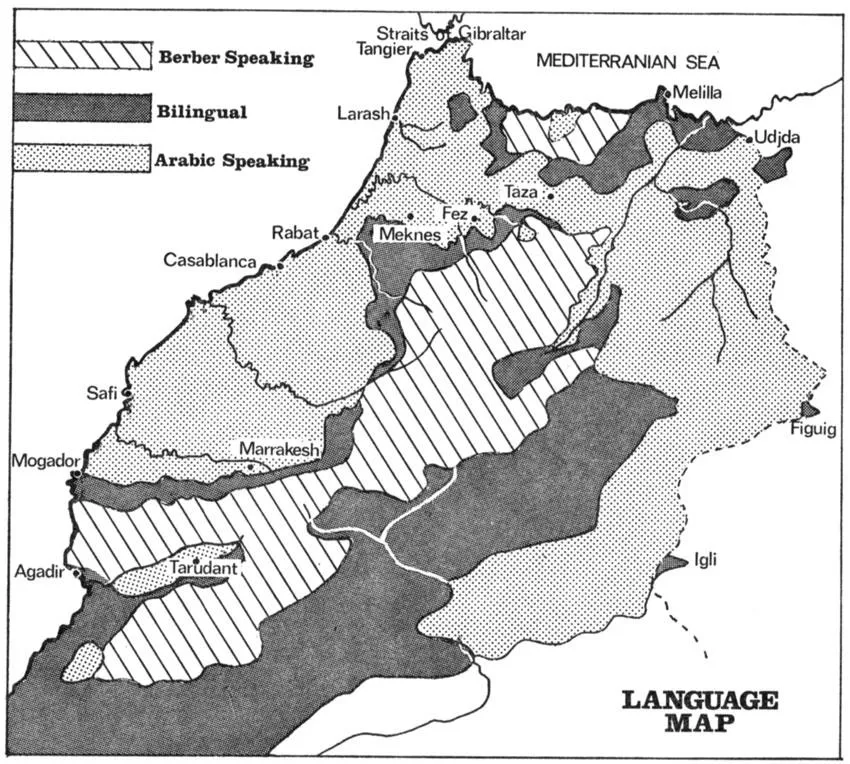

One can see that only in one single region of the Maghreb have the indigenous African populations retained their own dialects over a sizeable territory and in large numbers, and that is the mountain regions of Morocco against which the tide of the Arab invasion was halted. A linguistic map of Morocco will enable us to clarify the relationship between the different linguistic ‘forces’ in operation (see Map 2). Three areas can be identified: that of Arabic speech, that of Berber, and that of bilingualism. The area where Arabic is used is, generally speaking, that of the Atlantic plains, together with the Fes-Taza corridor and the desert regions. All the towns in Morocco fall within the Arabic-speaking area. Tarudant, the capital of the Suss—which is one of the heartlands of Berber culture—is surrounded by Arabic-speaking tribes: the Ulad Yahia, Menabbha and Hauara. We should mention specifically—and we shall make this point again later—that the huge area of the Atlantic plains is not inhabited entirely by groups of Arab origin, for there are certainly many tribes which were originally Berber. In the south, for example, there are the Dukkala and the Shiadma, who were still Berber-speaking in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries; in the north there are the tribes of the Jbala, which were probably Arabised much earlier as a result of influences from Andalusia.

The area where Berber is used exclusively is, speaking broadly, that of the high mountains, in the Rif and the Atlas; these are the last bastions of the linguistic resistance. The bilingual regions start at the edges of these areas. Here the women will speak Berber, while the men—or at least those whose occupations bring them in contact with the outside world—understand Arabic. One might say that this is the area where the Berber type of life, driven from the public sector and deprived of its freedom, has found refuge in the home.

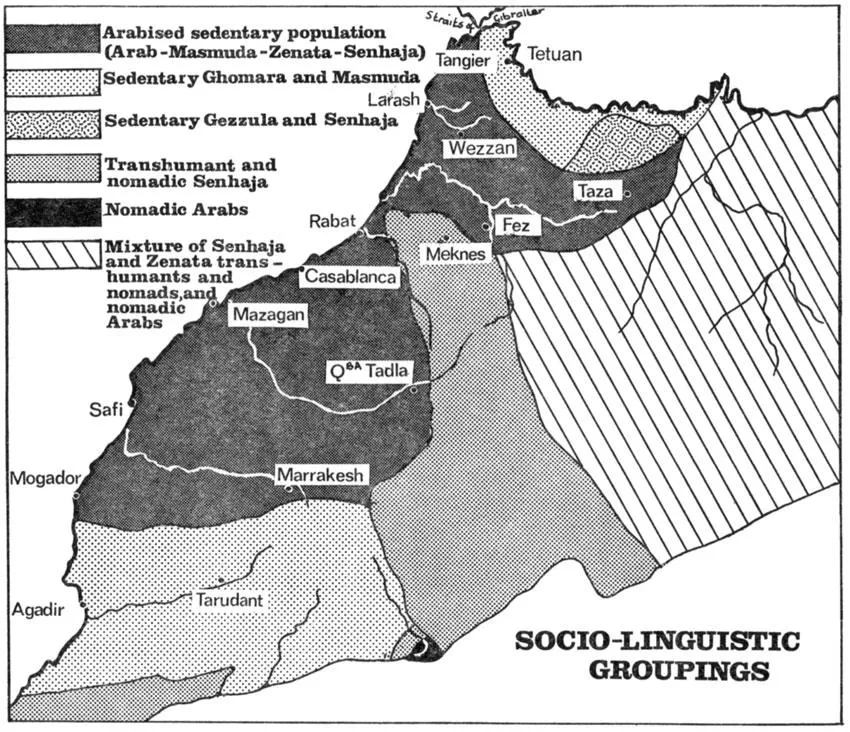

One can estimate that, out of six million inhabitants—and this is a very rough figure—about two and a half million maintain their use of Berber, whether in all fields of activity or merely in the home. A crude map of population distribution in Morocco supports these suggestions (see Map 3). We can distinguish:

1. The region of the Shleuh proper, who belong for the most part to great Berber families: the Masmuda and the Gezzula between the Wed Dra and the Atlantic, to the south of Marrakesh. This is a region inhabited by sedentary populations, living in villages and hamlets which, in the high mountain areas, continue to use the fortress storehouses called ‘agadirs’ The men of this region are hard-working and frugal; it is the area which, together with the Jurjura Kabylia, provides a massive labour force for France and the rest of North Africa.

2. The region of the Senhaja: transhumants of the Jebel Saghro and Jebel Aiashi who extend as far as the Middle Atlas and the plains of the Gharb. They make use both of tents and of ‘qasbahs’ (igherm, tighermt). This region is the land of sheep farmers, fierce and savage warriors upon whom Maurice Le Glay modelled his heroes.4 It is among these people that the tradition of Berber independence is best preserved.

3. The region of the transhumant Zeneta, who live mingled with Senhaja and Arab elements all along the Muluia up to the fringes of the eastern Rif. They live in tents and have no qasbahs. These pastoralists are frequently as difficult to control as the last group (2).

4. The region of settled farmers in the north of Morocco, where Ghomara and Senhaja intermingle. They tend to live in villages or else in scattered homesteads. Like the Shleuh they practise seasonal labour migration, although in this case it is directed largely towards Algeria.

5. The Arabised region of the plains, inhabited by sedentary populations of Arab (Hilal and Maʽqil) origin—particularly near the towns—and Berbers of various different ‘families’. A precise ethnic map would enable one to recognise elements from the four groups given above.

A rough classification of the tribes* made on the basis of their origins enables one to calculate the following numerical distribution: between ten and fifteen per cent of the tribes of Morocco are of genuine Arab origin. Examples are provided by the Ulad Jerrar, Menabbha and Ulad Yahia in the Suss, the Rehamna, Beni Meskin, Ahmar, Ulad bu Seba and Beni ‘Amir in the Atlantic plains, and the Sofian, Khlot and Haiaina in the Gharb. Even among these tribes we can distinguish the presence of discrete elements of Berber origin. Between forty and forty-five per cent of the tribes are Arabised Berbers, who may often claim to be Arabs but who can be assigned, on the basis of certain historical evidence, to one or other of the great Berber ‘families’. These tribes often contain Arab elements, whether families or whole fractions. Examples in this category are the ʽAbda, the Shawia and the Dukkala, or the gīsh5 of the towns, like the Ida u Blal and the Mejjat, or the tribes of the Sahara, like the Tekna. Finally, between forty and forty-five per cent are Berber tribes within which Arab elements constitute only a tiny minority.

It can be seen that the area where Arabic is spoken is that dominated by the towns, while Berber is exclusively a rural language. The phenomenon of Arabisation is, in fact, directly related to the influence of the urban areas on the surrounding tribes, and also to the influence of the Arab tribes gathered in these areas by the Sultans. There are many towns where Berber is spoken, but there are no city-dwellers who cannot speak Arabic. Arabic, because of its universal value, is the language used for the various transactions which take place between tribes speaking different Berber dialects, as well as being the language of religion and of the central government.

In what form is the Muslim religion introduced to the indigenous African population? It is necessary, at this point, and in order to avoid confusion and mistakes, to indicate clearly what are the major general features of Berber Islam. It has sometimes been said, with singular inaccuracy, that France drove the Berbers to Islam in North Africa and that she thereby made a serious political error by inadvertently reinforcing the barriers between these primitive peoples and our own civilisation with the unassailable bulwark of a religion which has frequently shown itself to be particularly uncompromising, and even hostile, towards the West. France had no need to encourage the Islamisation of the Berbers for the simple reason that the Berbers had been Islamised centuries ago.6 Their devotion to their faith is often even more noticeable than that of the Arabs. And they would certainly be astonished if they heard, from the fastnesses of their mountain retreats, that certain ill-informed Christians or Muslims in the towns hoped, or feared, that they might be converted to the Christian faith. In Berber areas, moreover, the religion has freely assumed a quite particular form, for the tribes have adapted it over the centuries to their own intellectual and political requirements.

It is known that Islam was not accepted without a great deal of resistance on the part of the Berbers during the first three centuries of the Hejira. Their opposition first of all took on a dual form: either they established heterodox sects—as the Persians did in the Middle East—to escape the constraints of the new religion, or else, on the contrary, they adopted a rigorous puritanism and called for an even stricter doctrine in reaction against the orthodox Islam of the towns, as a way of closing their homelands off from all external intervention. Moroccan heterodoxy had a brilliant career at first, and in fact until the eleventh century, with the false prophets of Berghuata, who translated an unusual version of the Qur’an into Berber and regarding whom Ibn Khaldun has left us certain details. It appears that Jewish influences played a significant part in the foundation of this ephemeral Berber religion. No less strange were Ha-Mim—false prophet of the Ghomara—and his kinsmen, who were able, by means of magical practices, to rally the mountain-dwellers of the Rif to their support, for a period of time at least. One should probably compare this religious ‘resistance’ with that which developed in the Atlas mountains under the name of Judaism and which appears to have been followed secretly until after the sixteenth century. In the absence of precise documentation one might surmise that the most independent of the Berber tribes (the Zeneta of the territory of the Beni Warain, the Senhaja of the Central Atlas and the sedentary populations of the Anti-Atlas) had the intention in the early centuries of turning aside the thrust of Islam by presenting themselves as Jews—who, in the eyes of the Muslims, were privileged as ‘people of the book’ (Ahl al-Kitab) and were distinguished from pagans who might, for their lack of faith, be put to the sword or sold into slavery. What appears to support this hypothesis is the fact that, even today, one finds the best-preserved traditions of Berber magic and the richest folk-lore among Muslim tribes regarded as being of Jewish origin, despite the fact that no traces of Judaism were previously observed in their traditions. These apparently Jewish tribes would therefore have been groups of Berber origin who put up a strong resistance during the first period of Islamisation. We know, furthermore, that in the time of Leo Africanus, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, there still remained, in several places in the Atlas, communities of Jews (or communities which were regarded as such) who owned land there and were prepared to defend it. One might suggest that these were the last remnants of Berber tribes which had, at an earlier date, taken up Judaism as a defence against the Muslim conquest.

The Berber tendency towards puritanism and austerity demonstrates a similar continuity. We sho...