- 390 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Designed for introductory students, this collection of key readings in language and linguistics will take readers beyond their introductory textbook and introduce them to the thoughts and writings of many esteemed authorities. The reader includes seminal papers, new or controversial pieces to stimulate discussion and reports on applied work.

Language in Use:

- is split into four parts – 'Language and Interaction', 'Language Systems', 'Language and Society' and 'Language and Mind'

- covers all the topics of language study including conversation analysis, pragmatics, power and politeness, semantics, grammar, phonetics, multilingualism, child language acquisition and psycholinguistics

- has readings from authorities including Pinker, Fairclough, Crystal, Le Page and Tabouret-Keller, Hughes, Trudgill and Watt, Halliday, Sacks, Mills, Obler and Gjerlow

- provides comprehensive editorial support for each reading with introductions, activities or discussion points to follow and further reading

- Is supported by a companion website, offering extra resources for students including additional activities, useful weblinks and advice from the authors

Designed for use as a companion to Introducing Language in Use (Routledge, 2005), but also highly usable as a stand-alone text, this Reader will introduce readers to the wide world of linguistics and applied linguistics.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 LANGUAGE AND INTERACTION

CONTENTS

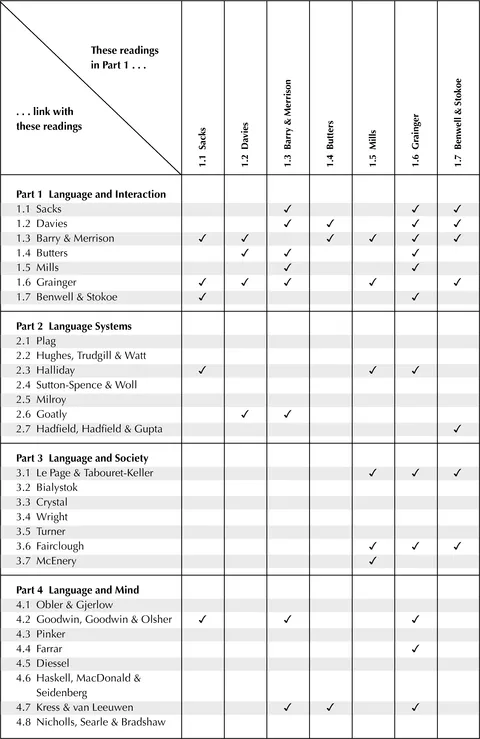

| Partmaps: Part 1 cross-references |

| Introduction to Part 1: Language and Interaction |

| 1.1 On the Preferences for Agreement and Contiguity in Sequences in Conversation |

| 1.2 Grice's Cooperative Principle: Meaning and Rationality |

| 1.3 Language-in-Use: a Clarkian Perspective |

| 1.4 How Not to Strike it Rich: Semantics, Pragmatics, and Semiotics of a Massachusetts Lottery Game Card |

| 1.5 Impoliteness |

| 1.6 Reality Orientation in Institutions for the Elderly: the Perspective from Interactional Sociolinguistics |

| 1.7 University Students Resisting Academic Identity |

Partmaps: Part 1 cross-references

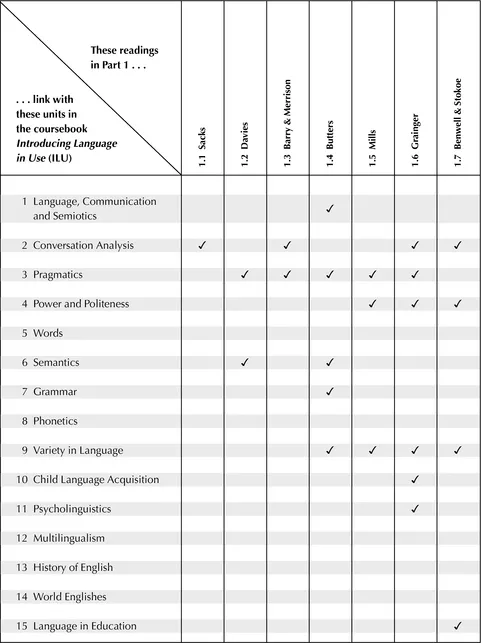

Partmaps: Part 1 cross-references to ILU

INTRODUCTION TO PART 1: LANGUAGE AND INTERACTION

We have called this book Language in Use: a Reader and we have divided it into four equally weighted parts. This first section is about language and interaction and it is perhaps not entirely accidental that, of the four parts, this is the first of our collection. Why? Because we firmly believe that it is here (i.e. in the inter-action) that language in use has its nexus.a

a All parts were created equal – it’s just that some parts are more equal than others!

Specifically, we subscribe to the following fundamental propositions about language:

- Language is USED

- Language is used FOR DOING THINGS

- Language is used for doing things BY PEOPLE

- Language is used for doing things by people INTER-ACTIVELY

- Language is used for doing things by people inter-actively and IS THUS INHERENTLY CONCERNED WITH THE CONSTRUCTION OF SOCIAL SELVES.

To demonstrate, let us borrow the words of some authors that we affiliate with.

I, II, III We should constantly remind ourselves that languages do not do things; people do things, languages are abstractions from what people do.

Le Page and Tabouret-Keller (1985: 188)

I, II, III, IV Language is used for doing things. People use it in everyday conversation for transacting business, planning meals and vacations, debating politics, gossiping. Teachers use it for instructing students, preachers for preaching to parishioners, and comedians for amusing audiences. Lawyers, judges, juries, and witnesses use it in carrying out trials, diplomats in negotiating treaties, and actors in performing Shakespeare. Novelists, reporters, and scientists rely on the written word to entertain, inform, and persuade. All these are instances of language use – activities in which people do things with language. [. . .] Language use is really a form of joint action.

Clark (1996: 3, original emphasis)

I, II, III, V When people use language, they do more than just try to get another person to understand the speaker’s thoughts and feelings. At the same time, both people are using language in subtle ways to define their relationship to each other, to identify themselves as part of a social group, and to establish the kind of speech event they are in.

Fasold (1990: 1)

THE READINGS

In their own ways, each of the seven readings in Part 1 touches on one or more of these five core propositions. They also seem to split into two main camps.

The readings about language being used for doing things by people interactively

Harvey Sacks is rightfully recognised as the founder of Conversation Analysis (CA). Sadly, while the discipline was still very young, he died in a car accident in 1975. The fact that Reading 1.1 (Sacks 1987, reproduced here in its entirety) was first published 12 years after his death and that we have chosen to include it in this volume (35 years after he died) is testament to the phenomenal legacy that he left behind. Having said that, ‘On the preferences for agreement and contiguity’ is not a particularly canonical paper – certainly it is not as well known as Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson (1974) on turn-taking; Schegloff, Jefferson and Sacks (1977) on repair; or Schegloff and Sacks (1973) covering adjacency pairs and closing conversations – but therein lie some of the reasons for including it here. First, these other papers are often available (or at least discussed at length) in other widely accessible publications (see Further Reading in 1.1). Second, unlike these published papers, this one still very much retains the flavour of the original spoken lecture: so many paragraphs begin with discourse markers we tend only to find outwith written texts (now, so, ok); it has audience participation in the final question–answer pair; and it has aspects of spoken delivery that show Sacks the person (‘Wow, that’s a fantastically neat thing to have seen’, ‘You know perfectly well that zillions of things work that way’). Admittedly, the 1400+ page collection of his (1995) Lectures on conversation also offers this ‘being there’ feeling, but the paper we reproduce here does not appear in that collection – a third reason for its inclusion here. Furthermore, unlike the Lectures (each of which was designed as one-in-a-series), this paper was originally delivered as a public lecture – a stand-alone entry-level unit – and this represents a fourth reason for the current choice. In short, we believe it represents very good value for money.

Reviewers have (sensibly) asked why we have included Reading 1.2 (Davies 2007) – a paper about Grice rather than a paper by Grice. The answers are simple. First, as well as the original 1975 paper in Cole and Morgan, ‘Logic of conversation’ is also available elsewhere (lightly edited in Grice 1989, more heavily edited in Jaworski and Coupland 2006, and reduced to secondary reportings in not only virtually every textbook on pragmatics, but also in so many introductory textbooks on linguistics – including Bloomer, Griffiths and Merrison 2005). Second, we considered the other papers of particular interest to linguists (such as Grice 1957, 1982) somewhat impractical as entry-level readings. Third, and most important, the point of Davies’ paper is to highlight that Grice’s most quoted paper has far too often been misinterpreted/misrepresented out of context, and to simply reproduce that paper may not have resulted in new students’ fullest appreciation of the issues involved, and may have simply (if inadvertently) reinforced those erroneous interpretations.

Reading 1.3 (Barry and Merrison 2009) is also presented in its entirety. And that is partly because it was originally written as a second-year undergraduate term paper. The course was taught by Andrew John Merrison and the paper was written by Becky Barry. She has allowed him to collaboratively tinker around the edges here and there, but essentially, the paper is largely as it was submitted. And that is one of the main reasons for its inclusion in this volume. Yes, it is an excellent introduction to Clarkian issues (sadly, a simple introductory text to Clark’s theory of Using Language does not exist (yet)) – and we believe that those ideas should be more widely accessible to students of language and linguistics – but it also shows what can be achieved even at an undergraduate level. And as this reader is pitched at students coming to these topics for perhaps the first time, we thought it was important to show that simply being a new student in the field does not necessarily mean being unable to contribute to it.

Following on from Readings 1.2 and 1.3, Reading 1.4 (Butters 2004) is a study of a particular case of situated making of and subsequent (mis)construal of meanings. It is also an applied study, in the sense that it involves the use of linguistic analysis to address a real world problem (viz. whether or not somebody has won – and therefore whether or not some other body has to pay out – $1 million).

The readings about language also being used for defining social selves

Being concerned with impoliteness, Reading 1.5 (Mills 2005) is clearly about interaction. But impoliteness is also necessarily about the negotiation of social meanings via linguistic means, and in this excerpt from a longer paper on gender and impoliteness, Mills offers us two main arguments about impoliteness: (i) that it ‘has to be seen as an assessment of someone’s behaviour rather than a quality intrinsic to an utterance’ (in other words, impoliteness is something people do), and (ii) it ‘can be considered as any type of linguistic behaviour which is assessed as intending to threaten the hearer’s face or social identity, or as transgressing the hypothesized Community of Practice’s norms of appropriacy’ (in other words, impoliteness is something people do that is interpreted according to conceptualisations of social selves).

Reading 1.6 (Grainger 1998), ‘Reality Orientation in Institutions for the Elderly: the Perspective from Interactional Sociolinguistics’, sells itself in its subtitle as both interactionally and socially orientated. It covers very many issues relating to this part,b and for that reason alone, we feel it is a good choice for this reader. It is, however, also suitable (and especially so for Part 1) as it is concerned more generally with social identities and social realities as they are co-constructed through day-to-day interactions. It is also an applied linguistics paper as it uses linguistic methods (here, Interactional Sociolinguistics) to provide insights into institutionalised issues (here, the effective management of the care of the confused elderly within National Health Service hospitals in the UK). Our final reason for its inclusion is that we feel it should be getting wider access by linguists than might be afforded to it by virtue of its publication in the Journal of Aging Studies.

b Including: caretaker talk (aka ‘baby talk’ or ‘motherese’); accommodation theory; linguistic politeness and face threatening acts; Grice’s cooperative principle; repair (in the form of overt correction); preference organisation; institutionalised talk; power.

Finally, there is Reading 1.7 (Benwell and Stokoe 2005), which is another paper reproduced in full. It is an applied conversation analytic account of students’ resistance to academic tasks and academic identity. In short, it seems that quite a few students (in the UK at least, though almost certainly more globally than that) appear to interact publicly as if they are not fully engaging in their university learning experience. The important point here is that the public appearance of non-engagement is not necessarily the same as actual non-engagement. Basically, it is not (currently) ‘cool’ to display an academic persona and so the identities involved in ‘doing education’ and ‘doing being a student’ are in direct conflict, and this has consequences for effective models of learning and teaching. Oh – and another reason we chose this paper was to let students know that their teachers know what they are up to! ☺

REFERENCES

- Bloomer, A., Griffiths, P. and Merrison, A.J. (2005) Introducing Language in Use: a Coursebook. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Clark, H.H. (1996) Using Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fasold, R. (1990) The Sociolinguistics of Language. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Grice, H.P. (1957) Meaning. Philosophical Review 66, 377–88.

- Grice, H.P. (1975) Logic and conversation, in P. Cole and J.L. Morgan (eds) Syntax and Semantics, vol. 3. New York: Academic Press, 41–58.

- Grice, H.P. (1982) Meaning revisited, in N.V. Smith (ed.) Mutual Knowledge. New York: Academic Press, 223–43.

- Grice, H.P. (1989) Studies in the Way of Words. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Jaworski, A. and Coupland, N. (eds) (2006) The Discourse Reader (2nd edn). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Le Page, R.B. and Tabouret-Keller, A. (1985) Acts of Identity: Creole-based Approaches to Language and Ethnicity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sacks, H. (1995) Lectures on Conversation, Volumes I and II. Edited by Gail Jefferson. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Sacks, H., Schegloff, E.A. and Jefferson, G. (1974) A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language 50 (4), 696–735.

- Also in J.N. Schenkein (ed.) (1978) Studies in t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Acknowledgements

- Read me (before you read anything else in this Reader)

- Bookmaps

- Transcription conventions

- Prologue

- PART 1 LANGUAGE AND INTERACTION

- PART 2 LANGUAGE SYSTEMS

- PART 3 LANGUAGE AND SOCIETY

- PART 4 LANGUAGE AND MIND

- Epilogue

- Index

- Useful websites

- International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) Chart

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Language in Use by Patrick Griffiths,Andrew John Merrison,Aileen Bloomer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.