- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The musical tradition of Ma'luf is believed to have come to North Africa with Muslim and Jewish refugees escaping the Christian reconquista of Spain between the tenth and seventeenth centuries. Although this Arab Andalusian music tradition has been studied in other parts of the region, until now, the Libyan version has not received Western scholarly attention. This book investigates the place of this orally-transmitted music tradition in contemporary Libyan life and culture. It investigates the people that make it and the institutions that nurture it as much as the tradition itself. Patronage, music making, discourse both about life and music, history, and ideology all unite in a music tradition which looks innocent from the outside but appears quite intriguing and intricate the more one explores it.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Ma'luf in Contemporary Libya by Philip Ciantar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Libya: Society, Culture and Music

How fine, dignified and intriguing is this Libyan race! Who would have the heart to interfere with this simple people in their tranquil, pastoral ways? How many reflections on the vanity of modern civilization cross one’s mind on entering one of these tents ….

(Camperio 1912, Pioneri Italiani in Libia [trans. Wright 2005: 191])1

My Libya diary begins from home, Malta—an island country only an hour flight away from Libya. The first fieldwork note is dated 2 April 2002, the day when I was to leave for my first trip to Libya as guest of the Islamic Call Society (Jama῾iyyat ad-Da῾wa al-Islamiyya).2 During that trip I was supposed to meet Hassan Araibi, Libya’s main exponent of the ma’lūf. However, the previous day, at around 9 p.m., I had received a phone call from the Society’s representative in Malta informing me that the trip was being postponed to a later date. Consequently, the tone of my first note was sombre, full of disappointment, although inquisitive at the same time:

Today I was supposed to leave for Libya; however, I was informed yesterday by the Islamic Call Society in Malta that my trip is being postponed to a later date which will be communicated to me later on. A really big disappointment when I had everything prepared. The reason that I was given was that Hassan Araibi was in Dubai and, therefore, it wasn’t possible for me to meet him. However, in a telephone conversation that I had afterwards with a Libyan friend of mine residing in Malta and a person close to the Society, he indicated to me that the Society was very preoccupied over my security due to massive demonstrations being held in Tripoli in support of the Palestinians and against the besiegement of Yasser Arafat in his West Bank quarters.

Apart from the Palestinian incident, my first planned trip coincided with a time when Libya had just started to recover from the international sanctions imposed on it by the United Nations Security Council in 1992, which sanctions included an embargo on air travel. The sanctions came into effect after Libya had refused to extradite two Libyan nationals considered by the United States and the United Kingdom to be the culprits of the US Pan American Airways airliner bombing of 21 December 1988 over the Scottish village of Lockerbie. The French government had also requested the extradition of six Libyans suspected of involvement in the UTA flight 772 bombing on 19 September 1989 when an aircraft with 170 passengers blew up en route from Brazzaville to Paris. As in the case of the former request, this request was rejected by the Libyan government. Following the lifting in 2001 of the imposed air embargo, which had put Libya in absolute isolation, the country’s airports gradually started to return to normality, with European airway companies such as British Airways, Alitalia and Air Malta fixing weekly flight schedules to Tripoli, Libya’s capital.

My first trip took place on 6 June 2002, two months later than planned. Most of the passengers on board were Maltese working in Libya’s petroleum industry and related jobs. The two Maltese gentlemen sitting next to me on the flight seemed to know each other very well as they chatted all the way through. As the plane touched down at Tripoli Airport at 2.00 p.m. we were informed that the temperature outside the aircraft had reached 41°C! The two gentlemen sitting next to me commented that in 1922 the temperature had reached almost 58°C. ‘I hope it won’t go up that much whilst I’m here’, I intervened jokingly in an attempt to start some last-minute conversation. ‘Everything is possible to happen here … it’s better for you to get prepared for any eventuality’, one of them replied smilingly. ‘Are you working here?’, asked the other one. ‘I’m here to carry out research on Libyan music’, I replied hastily. ‘Libyan music …?!’, exclaimed the first. ‘Will you be working on music in the desert?’, he asked again with a somewhat shrill voice of surprise. ‘We work on an oil rig in the desert and occasionally we hear music coming to us in the evening. You’re most welcome to visit us if you want to do research there’, he added whimsically whilst standing to line up in the queue moving out of the aircraft, hardly giving me the chance to thank him. His descriptive snippet reminded me of the accounts I had read a few days before of Western travellers’ expeditions in the Sahara, riding on camelback and struggling with the hard conditions of the most arid place on earth, the largest area of dry desert in the world. My thinking could not be prolonged, though, as I too had to join the queue on its way out of the aircraft to begin my first onsite experience of and encounter with Libyan society, life and music.

Based on those onsite experiences, this chapter aims to put together a socio-cultural and musical backdrop for the Libyan musical tradition we are concerned with in this book. It aims to bring forth some of the dichotomies, if not also paradoxes, that coexist in Libya’s culture and, by extension, musical domain. Such ideas and debates concern aspects related to issues such as ‘modernism’ versus ‘traditionalism’, the ‘old’ and ‘new’ and the blending of both, as well as the identification of what is considered as ‘local’ or ‘imported’. The jumbled sounds and aspects of Libya’s musical life highlighted in this chapter—with which the ma’lūf not only coexists but sometimes merges intrinsically—can be partially explained, if initially placed within a conventional order, commencing with a description of the land and the people inhabiting it, together with a short historical survey of Libya that locates Gaddafi’s 1969 revolution in a historical chronology. This is then followed by a discussion concerning music and related cultural and educational policies in the post-1969 revolutionary years that in some way or another had an impact on Libyan music in general and the ma’lūf in particular. Following that, a discussion will unfold concerning the different aspects of Libya’s contemporary musical life as Tripoli’s emerging diverse soundscape. Other musical domains treated in this chapter include Libya’s folk music and its role in contemporary musical life and the official culture more widely, the recording industry and its proliferation in the post-1969 revolutionary era and, finally, formal music education in Tripoli and the making of the professional musician. All this aims to contribute towards the construction of the context that will assist us in retrieving ‘what lies behind’ the Libyan ma’lūf tradition and its role in today’s Libya.

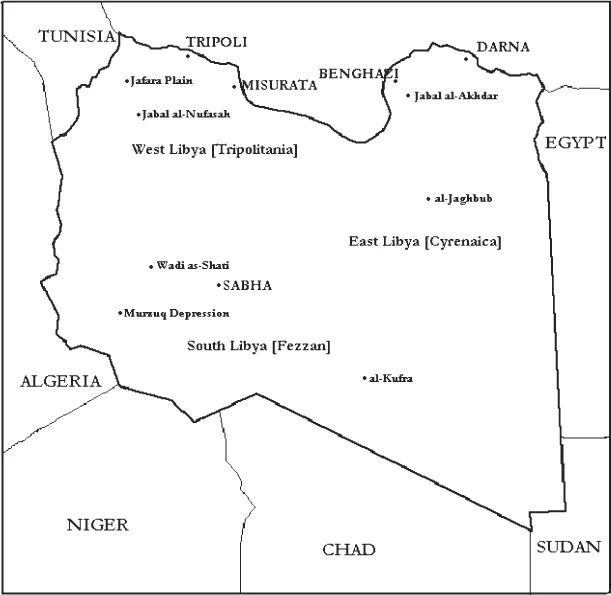

The Land and the People

Libya is a vast North African country with land covering an area of 1.8 million square kilometres, 90 per cent of which is desert. This makes its area the fourth largest in Africa and the seventeenth largest in the world.3 At the time of the present research, Libya’s population was 5.7 million, 1.7 million of whom resided in the capital, Tripoli. Its 1,900 km coastline borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north whilst inland it borders Egypt to the east, Sudan to the south-east, Niger and Chad to the south, Algeria to the west, and Tunisia to the north-west (see Figure 1.1). Due to its strategic geographical position between Africa and Europe, Libya has always served as a natural trading route between the two continents. In addition, its position between the Maghreb (West) and Mashriq (East) countries of the Arab world has over the years facilitated transit missions between the two areas.

Most of Libya’s population is composed of Arabic-speaking Muslims of mixed Arab and Berber ancestry. Libya’s population also comprises Greeks, Maltese, Italians, Egyptians, Afghanis, Turks, Indians and sub-Saharan Africans.4 Considering its large territory, Libya is one of the least densely populated nations in the world. In fact, 90 per cent of its population lives in less than 10 per cent of its territory, mostly along the Mediterranean coast. More than half of the population is urbanized and mostly concentrated in the two largest cities of Tripoli and Benghazi. Since the 1960s ‘the benefits of modernization have tempted most tribal people to swap tough conditions for a more comfortable and stable life in the towns—government schemes have provided new housing in the larger oases’ (Hardy 2002: 66).

Figure 1.1 Libya in North Africa

Historically, Libya was divided into three regions: Tripolitania in the north-west, Cyrenaica in the east and the Fezzan in the south-west. Nowadays, these three regions are known as West, East and South Libya. The Tripolitanian region embodies a fertile north-western peninsula known as Jafara that extends towards a hilly area known as Jabal al-Nufasah. The capital Tripoli, took its name from the region in which it is situated. The Cyrenaica region in East Libya comprises a narrow fertile coastal strip with a high plateau covered by trees known as Jabal al-Akhdar (the Green Mountains), as well as the city of Benghazi, considered to be the second largest city in Libya. With the exception of some scattered oases like those of al-Jaghbub and al-Kufra, the lowlands south of Jabal al-Akhdar are mostly deserted. This part of the desert is one of the most arid places on earth and is considered to be the largest area of dry desert in the world. To the south, the region of the Fezzan comprises a number of scattered oases like those of Murzuq and Wādī ash-Shāṭī. The Fezzan also contains the town of Sabha situated 800 kilometres south of Tripoli. Considering Libya’s vast land area and the large stretches of desert that for years have separated urban areas such as Benghazi and Sabha from Tripoli (this being the cradle of the ma’lūf tradition in Libya), one can understand why, in those circumstances, it was difficult for the ma’lūf to reach with strong diffusion remote urban areas like those mentioned above. Until present times, although one might find ma’lūf performed in Benghazi and Sabha, its popularity there is incomparable to that in Tripoli. Several Libyans I spoke to insisted that the ma’lūf remained concentrated in Tripoli even after the unification of the three regions in 1963, when the mobility of ma’lūf musicians could have been facilitated by the newly constructed network of highways and air routes.

Libya Until the 1969 Revolution

In ancient times the area that is now known as Libya was colonized by both the Phoenicians and the Greeks.5 The latter used to refer to the entire North African region—excluding Egypt—as Libya. The Greeks thought that all the people living in North Africa looked alike, and therefore they attributed to them the name Lebu; the Lebu people are nowadays known as Berbers. At this time the country was divided into two major provinces, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, with the Phoenicians occupying the former and the Greeks the latter. Punic settlements on the Libyan coast included Oea (Tripoli), Labdah (later Leptis Magna) and Sabratah, in an area that came to be known collectively as Tripolis, or the ‘Three Cities’. Moreover, the Phoenicians had built up an efficient agricultural infrastructure and a sophisticated system of trade, leaving desert trade in the hands of the desert people themselves. In the fifth century BC Tripolitania was incorporated into the Carthaginian Empire, while in around 500 BC Cyrenaica was annexed to the Persian Empire. All of Libya was then ruled in turn by the Egyptians (323 BC), Romans (74 BC), Vandals (AD 455) and Arabs (AD 643).

The Arab conquest is considered to be the one that has had the most profound and lasting influence on the country. Both the religion (Islam) and the language (Arabic) of Libya came from the Arabs, and have lasted over the centuries. The Arabs were diffused all over the country and eventually integrated with the local inhabitants. In 1500 the Spanish landed in Tripoli and ruled it until 1530 when Emperor Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, bestowed it on the Order of the Knights of St John. Fifty-one years after the Spanish conquest, in 1551, the Turks captured Tripoli from the Knights and integrated it into the growing Ottoman Empire, which at that time already included Cyrenaica, Egypt, Algeria and Tunisia. Under the Ottomans, Tripoli became the headquarters of the Barbary pirates. In all, the Ottomans ruled Libya for more than 300 years (1551–1912) during which period Libyan prosperity degenerated.

In the meantime, a Sufi Order was founded in Mecca in 1837 by Sayid Muhammad bin Ali al-Sanusi al-Idris al-Hasani, an Algerian and grandfather of Idris, Libya’s first king. The Sunni movement was established with the aim of restoring the purity of Islam and assisting its members. The founder chose Cyrenaica as a centre for his movement and settled there in 1843. Later on the movement spread all over Cyrenaica and Fezzan through the establishment of several Sufi lodges (or zawāyā). These lodges gained importance not only as centres of learning and religion but also as a source of political influence for the Sanusis (as the followers of the founder were known). Evans-Pritchard (1949: 80) describes the role of the zāwiya (singular of zawāyā) as follows:

Sanusiya lodges served many purposes besides catering for religious needs. They were schools, caravanserai, commercial centres, social centres, forts, courts of law, banks, besides being channels through which ran a generous stream of God’s blessing. They were centres of culture and security in a wild country and amid a fierce people and they were stable po...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Musical Examples

- Technical Notes

- Preface

- 1 Libya: Society, Culture and Music

- 2 The Nawba in North Africa and in Libya

- 3 The Ma’lūf al-Idhā῾a: Change, Continuity and Contemporary Practices

- 4 The Musical Making of Ma’lūf

- 5 The Libyan Ma’lūf in the Realm of Arab Music Aesthetics

- Epilogue

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index