![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Lost Link between Heaven and Earth

Heaven is my father and Earth is my mother,

and even such a small creature as I find an intimate place in their midst.

Therefore that which fills the universe I regard as my body and

that which directs the universe I consider as my nature.

All people are my brothers and sisters, and all things are my companions.

– Zhang Zai, 1020-1078, Western Inscription; cited in Chan, 1969, p. 497

Traditional Courtyard Houses

The courtyard house is one of the oldest dwelling typology, spanning at least 5,000 years and occurring in distinctive forms in many parts of the world across climates and cultures, such as China, India, the Middle East and Mediterranean regions, North Africa, ancient Greece and Rome, Spain, and Latin-Hispanic America (Blaser, 1985, 1995; Edwards et al., 2006; Land, 2006, p. 235; Pfeifer and Brauneck, 2008; Polyzoides et al., 1982/1992; Rabbat, 2010; Reynolds, 2002).

Archaeological excavations unearthed the earliest courtyard house in China during the Middle Neolithic period, represented by the Yangshao culture (5,000-3,000 BCE) (Liu, 2002a). The ancient Chinese favored this housing form because enclosing walls helped maximize household privacy and protection from wind, noise, dust, and other threats; and the courtyard offered light, air, and views, as well as acting as a family activity space when weather permitted (Knapp, 2005a; Wang, 1999).

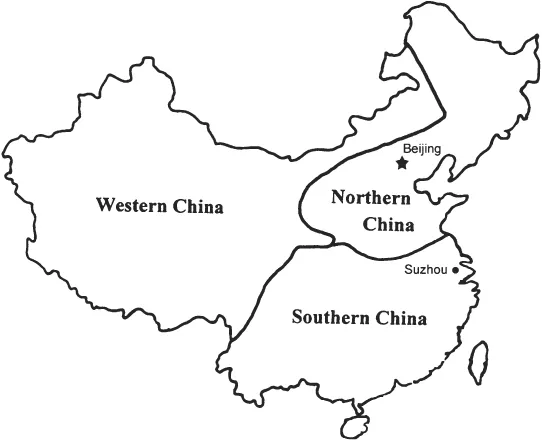

There was a distinctive variety of traditional courtyard houses due to China’s wide-ranging climates, 56 ethnic minority groups, and notable linguistic and regional diversity even among the Han majority. Hence, traditional Chinese courtyard houses were grouped as northern, southern, and western types according to their geographic locations in relation to the Yangzi River (Knapp, 2000, p. 2; figure 1.1). Chinese city planning and courtyard houses first emerged in the north and eventually appeared in the south due to migration (Knapp, 2000, p. 223; Wu, 1968). Cultural diffusion began during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) when core populations were encouraged to move to other parts of China to enhance their growth; most settlers built new residences in the style of their original homes (Sun, 2002). This confluence of building patterns demonstrates the layers and veins of acculturation within China over the centuries.

Figure 1.1 Map of China showing the northern, southern, and western divisions with locations of Beijing and Suzhou as the case study cities. Source: adapted from Knapp, 2000, p. 2 © 2005 University of Hawaii Press. Reprinted with permission

Chinese builders throughout the country have historically favored a number of conventional building plans and structural principles such as bilateral symmetry, axiality, hierarchy, and enclosure. Courtyards or lightwells (天井 tianjing, or ‘skywells’) were important features in the layout of a fully built Chinese house. Philosophically, the courtyards acted as links between Heaven and Earth, as during the Han dynasty (c.206 BCE-220 CE), the Chinese regarded Heaven and Earth as a macrocosm and the human body a microcosm to reflect the universe (Chang, 1986, p. 200); offering sacrifices to Heaven and Earth in courtyards was considered crucial to bringing good fortune (Flath, 2005, pp. 332-334).

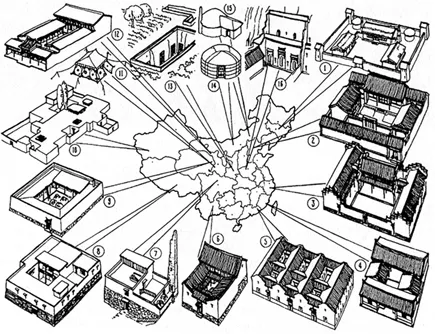

Across China, four basic types (and their sub-types) of traditional courtyard houses are found:

1. 1-storey square/rectangular-shaped courtyard houses (siheyuan) in the northeast such as in Beijing, Hebei, and Shandong; 1-2-storey rectangular courtyard houses that are longer in the north-south direction to maximize sunlight in the north such as in Shaanxi and Shanxi;

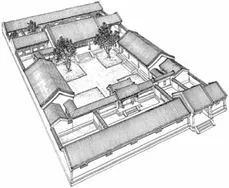

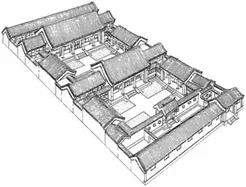

Figure 1.2 House types across China showing the courtyard as a common feature. Source: Drawing by Fu Xinian in Liu, 1990, p. 206

2. 2-3-storey courtyard/lightwell houses that are longer in the east-west direction to filter out summer’s hot sun in such southern regions as Jiangsu; 2-storey inverted U-shaped courtyard/lightwell houses (sanheyuan and yikeyin) in central and southern provinces such as Sichuan, Hunan, Anhui, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong, Guanxi, Yunnan, and Taiwan;

3. 3-4-storey fortresses in circular, elliptical, or octagonal structures (tulou) that house groups or entire clans in southern regions such as Fujian, Guangdong, and Jiangxi;

4. Cave-like sunken, earthen, or subterranean courtyard houses in northern and northwest regions such as Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Henan (Knapp, 2000, 2005a; Liang, 1998; Wu, 1999).

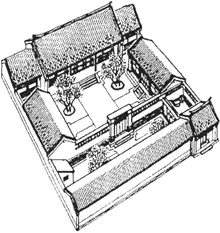

Beijing siheyuan are commonly regarded as the most outstanding examples of traditional northern Chinese courtyard houses.

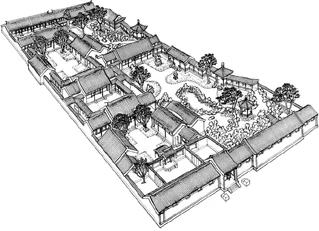

Traditional Suzhou courtyard houses are representative of the southern type, generally with smaller courtyards and gardens to admit less sunlight due to their hot summers.

Figure 1.3 A two-courtyard house of Beijing. Source: Liu, 1990, p. 210

Figure 1.4 A typical or standard three-courtyard house of Beijing. Source: Ma, 1999, p. 7

Figure 1.5 A relatively large four-courtyard house of Beijing. Source: Ma, 1999, p. 19

Figure 1.6 A five-courtyard house of Beijing with gardens. Source: Ma, 1999, p. 227

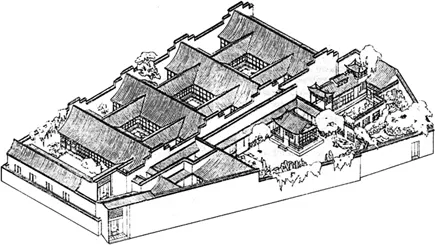

Figure 1.7 A large courtyard house compound in Suzhou. Source: Wu, 1991c, p. 58

Figure 1.8 A typical southern type of courtyard house complex with small courtyards and gardens in Yangzhou, China. Source: Schinz, 1989, p. 58, Urbanisierung d. Erde, Vol. 7, Borntraeger Science Publishers, www.borntraeger-cramer.de

Decline of Courtyard Houses

Traditional Chinese courtyard houses have undergone changes over the years. The Qing dynasty (1644-1911) was the peak period for the development of courtyard houses. However, British and French attacks from the 1840s, the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, and Japan’s two invasions during 1894-1895 and 1937-1945 forced a massive population move from the suburbs into the cities, resulting in a severe urban housing shortage and rendering most citizens’ livelihood increasingly more difficult. With rapidly increasing prices, many households started renting out rooms in their courtyard houses to help with living expenses. Consequently, the originally single-extended-family homes became multifamily compounds, and the very nature of traditional Chinese courtyard houses changed (Bai, 2007; Ma, 1999).

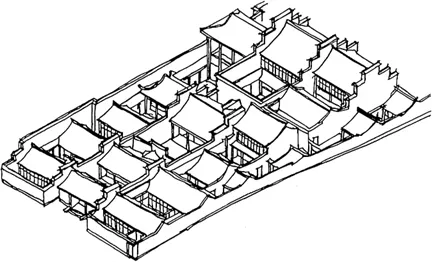

With the establishment of People’s Republic of China in 1949, the country’s population expanded rapidly. Subsequently, the evolved 4-5-family courtyard houses increased capacity to shelter over 10 families upon their children’s marriages. New kitchens, storage spaces, and even bedrooms built into the courtyards turned the ordered enclosures into disordered quarters. These changes made it difficult for the courtyard houses to maintain their original charm, mystique, tranquillity, and cosiness (Bai, 2007; Ma, 1999; Zhu, Huang, and Zhang, 2000, p. 8).

During the ‘Cultural Revolution’ (1966-1976), traditional Chinese courtyard houses sustained the most severe damages. Systematic destruction was launched in 1966 to demolish the ‘Four Olds’ (old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits). Red Guards chiselled out uncountable amounts of invaluable artwork of brick, wood, and stone carvings; they also ruined colorful decorations on courtyard houses, after which, the few surviving houses were either plastered over, repainted, or simply left in their own wreckage. This devastation led not only to demolished courtyard houses, but an irreversible, fatal assault on Chinese art and architecture (Knapp, 2005a; Ma, 1999; J. Wang, 2003, p. 335).

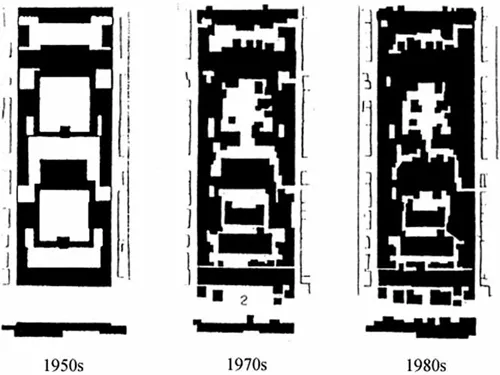

More damage was still on the way. In March 1969, at the height of the Sino-Soviet split, a border conflict occurred in Zhenbao Island that led to a nation-wide ‘Excavation Movement’1 on the Chinese side to prepare for Russian attacks, but which further destroyed traditional courtyard houses’ structures. In Beijing, this movement was eclipsed by the 1976 Tangshan Earthquake that was like ‘frost on snow.’ To provide refuge, many ‘anti-quake sheds’ were added to already overcrowded courtyards. These temporary shelters became permanent and distorted Beijing siheyuan beyond recognition (Bai, 2007; Ma, 1999; figure 1.9).

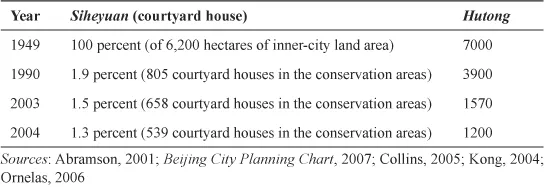

Since the 1990s, China’s rapid economic growth coupled with an unprecedented level of real estate development has resulted in the almost wholesale destruction of traditional courtyard houses. For example, until 1949, Beijing was a completely traditional courtyard city. In the early 1950s, Beijing’s inner city had 11 sqkm of single-storey siheyuan, of which only 5-6 percent was dilapidated. At the end of the 1980s, most parts of inner Beijing were still occupied by siheyuan of various qualities. However, in 1990, the inner city had total single-storey siheyuan of 21.42 sqkm, of which almost 50 percent was decaying. The increased floor space from 11 sqkm to 21.42 sqkm was due to the proliferation of improvised extensions, an indication that not much courtyard was left. Between 1990 and 1999, a total of 4.2 sqkm of Beijing siheyuan were demolished, with its areas shrunk from 17 sqkm to 3 sqkm between the early 1950s and 2005 (Tan, 1998; Yuan, 2005). Today, the few well-preserved hutong (‘lane’) with refurbished siheyuan serve only high officials and those who can afford such homes (Trapp, 2002?, p. 5; Zheng, 2005).

Figure 1.9 Decline of a courtyard house compound in Beijing from early 1950s – 1970s – 1980s. Source: Zhu and Fu, 1988

Table 1.1 Extent of survival of siheyuan and hutong in inner Beijing

The massive destruction of traditional Chinese courtyard houses was followed by housing redevelopment to alleviate acute housing shortage. From the late 1950s to the late 1970s, the Chinese government constructed large numbers of new residential quarters of 4-5-storey parallel ‘Socialist Super Blocks’ influenced mainly by the Soviet Union (Dong, 1987; Gaubatz, 1995, 1999). Between 1974 and 1986, the Beijing Municipal Government built around 7 sqkm of new housing in the inner city which accounted for 70 percent of the city’s total housing redevelopment since 1949 (Wu, 1999), most of which consisted of residential tower blocks of over 10 storeys comprised of individual apartments. By the end of 1996, new housing projects numbered over 200, covering 22 sqkm of inner Beijing (Tan, 1997, 1998). In Suzhou, between 1994 and 1996, nearly 3 million sqm of new housing were added to the housing stock each year (Zhu, Huang, and Zhang, 2000, p. 3).

Such a large scale housing redevelopment has had a major impact on the historic cities’ overall structure, land-use pattern, and cultural sites. Although each new apartment has the advantage of privacy and facilities, not to be underestimated when compared with the old, dilapidated courtyard houses from which many of these residents came, and the mid- and high-rises had eased some desperate housing demands, most of them did not include a courtyard – the traditionally important link between Heaven and Earth was lost. Chinese urban areas are extending and transforming at such phenomenal speed that the intangible value of traditional dwelling culture runs the danger of uncontrolled elimination (Acharya, 2005; Collins, 2005; Chatfield-Taylor, 1981; Entwurf, 2005; Gaubatz, 1995, 1999; Mann, 1984; Marquand, 2001; Nilsson, 1998; Ornelas, 2006; Reuber, 1998; Schell, 1995; Spalding, n.d.; Tung, 2003; Van Elzen, 2010; W. Wang, 2006; Watts, 2007; Whitehand and Gu, 2006; Wood, 1987).

As early as the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE), China had already launched debates concerning high-rise buildings with the concluding remark that they were “too far to harmonize Heaven and Earth, therefore drop the idea”2 (Luó, 1998; Luò, 2006, p. 109; J. Wang, 2003, p. 146; my translation). A growing body of literature provides evidence for the unnatural and harmful impacts of tower blocks not only on Chinese cultural landscapes, but also on the wellbeing of occupants, particularly that of the elderly and children (Bosselmann et al., 1984; Ekblad and Werne, 1990a, 1990b; Ekblad et al., 1992; Lu, 2004, p. 333; Stewart, 1970; Tan, 1997; J. Wang, 2003, p. 145; Wu, 1999; Yan and Marans, 1995).

Numerous housing studies suggest that despite traditional courtyard houses’ physical deteriorations and poor living conditions (He, 1990; Lu and He, 2004; Wu, 1999, p. 112), Beijing residents prefer ...