eBook - ePub

Muslim Families, Politics and the Law

A Legal Industry in Multicultural Britain

- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

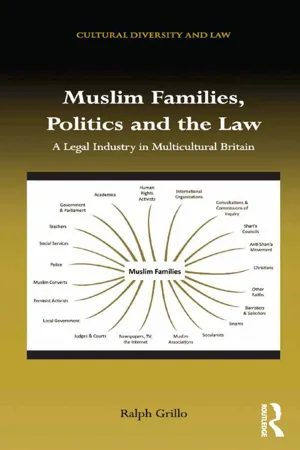

Contemporary European societies are multi-ethnic and multi-cultural, certainly in terms of the diversity which has stemmed from the immigration of workers and refugees and their settlement. Currently, however, there is widespread, often acrimonious, debate about 'other' cultural and religious beliefs and practices and limits to their accommodation. This book focuses principally on Muslim families and on the way in which gender relations and associated questions of (women's) agency, consent and autonomy, have become the focus of political and social commentary, with followers of the religion under constant public scrutiny and criticism. Practices concerning marriage and divorce are especially controversial and the book includes a detailed overview of the public debate about the application of Islamic legal and ethical norms (shari'a) in family law matters, and the associated role of Shari'a councils, in a British context. In short, Islam generally and the Muslim family in particular have become highly politicized sites of contestation, and the book considers how and why and with what implications for British multiculturalism, past, present and future. The study will be of great interest to international scholars and academics researching the governance of diversity and the accommodation of other faiths including Islam.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Muslim Families, Politics and the Law by Ralph Grillo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Law Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Cultural Diversity and the Law

Introduction

On three occasions in 2011–14, Baroness Caroline Cox, a member of the UK’s House of Lords, introduced a Private Members’ Bill,1 the Arbitration and Mediation Services (Equality) Bill, to make it a criminal offence, punishable by imprisonment, if a person ‘falsely purports to exercise any of the powers or duties of a court or to make legally binding rulings’ (see Appendix for the principal clauses). It was one of four bills under discussion in that period, each of which proposed to criminalize practices which many associated with British Muslims. The others were Philip Hollobone’s Face Coverings (Prohibition) Bill, outlawing the public wearing of face-veils,2 and the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing and Immigration Bills relating respectively to forced and sham marriages. Part II of this book (Chapters 7–11) follows the ‘career’ of Baroness Cox’s initiative which would have serious, possibly crippling, implications for the activities of bodies concerned with religious mediation and arbitration, including the Shari’a3 councils which operate within Muslim communities in Britain. It examines how the Bill was promoted and by whom, describes the arguments for and against and considers whether opposition to the councils (often incorrectly called ‘courts’) can be ascribed to ‘Islamophobia’.

The present chapter and Chapter 2 set this and other calls call for legislation in the wider context of debates about Islam in Britain, outlining the social and political background of Muslim immigration and settlement, the growing tension around Islam, and disquiet about the rise of religious councils. Part I (Chapters 3–6) groups a series of case studies on marriage and divorce. Muslim families are caught up in socio-legal and political arguments and cultural and social disputes about meaning and practice, with issues such as marriage registration, forced and arranged marriages and divorce disputed among and between Muslims and non-Muslims, reviewed in consultations, discussed in Parliament, tested in the courts, with Muslim religious leaders, and their critics and supporters, increasingly prominent in public life. Chapter 6, a pivotal chapter, draws on material presented in Part I and prepares the ground for Part II by reviewing different narratives of the ‘Muslim woman’ found in those debates (for example as victim or ‘survivor’, as hero(ine) and as obedient wife), which stem from different understandings of what constitutes agency, patriarchy, domestic abuse, mediation, community relations and so on. Finally, Chapter 12 considers whether there is room for constructive dialogue between Muslims and others, addressing and perhaps resolving differences.

Background

Contemporary European societies are all, in varying degrees, multi-ethnic and multicultural in terms of the diversity which has stemmed from the immigration of workers and refugees and their settlement. Currently, however, there is a widespread, acrimonious, debate about cultural and religious difference and its limits. There is scarcely any country in the West, or elsewhere, where this is not an issue, as may be observed in newspapers, television and the Internet, in election manifestos, parliamentary debates and ministerial statements, in policy initiatives at local, national and international levels and in the daily preoccupations of, for instance, social workers and teachers. Lawyers, too, are among the many groups and individuals touched by the law who confront different beliefs and practices and their possible ‘accommodation’. Interaction with cultural diversity is thus a central concern of this book. Its context is Britain, and while Muslims are by no means the only ‘others’ (Hindus and Sikhs certainly enter into the picture), it concentrates on their situation.

Although scholars have long contemplated these matters, in the current conjuncture they have assumed increasing importance, as is demonstrated by a plethora of publications.4 Although Judge David Pearl had, in 1995, noted the growing range of questions concerning marriage, divorce, inheritance, the custody of children and so on with which courts were having to deal, an authoritative account of Family, Law and Religion in England and the USA (Hamilton 1995) had, relatively speaking, little coverage of Islam and Muslim practices, compared with what it might have done had the book appeared 25 years later: so much has happened in the intervening period and there are several interconnected reasons for this.

First, there are some 15–18 million Muslims in Western Europe, with the 2011 census recording 2.7 million in England and Wales, c. 5 per cent of the population (Office for National Statistics 2012b), significantly up from 2001 (3 per cent). They are found in all parts of the country with substantial concentrations in London, especially East London, and in other conurbations including the West/East Midlands, Manchester and West Yorkshire. The vast majority (perhaps 96 per cent) are followers of different strands of Sunni Islam (the Shi’a population is relatively under-documented).5 They are not, however, homogeneous. Bowen (2014) is a valuable compendium of information about the main ideological tendencies among British Muslims, based on extensive interviews with the principal actors. Her study, which concentrates on organizations (religious, political and both), their ideological position within Islam, their local leadership and international connections, shows that doctrinal and other disputes are many and vigorous, with ethnic and similar allegiances often aligned with religious difference.

Secondly, the Muslim population is now predominantly a family one. Although many migrants (women and men) were originally ‘single’, and anticipated returning to countries of origin, others, unintentionally or perforce, became settlers, bringing or sending for partners and children or establishing new families in situ: Gilliat-Ray (2010) has an excellent summary of the literature on marriage and the family among people of South Asian background, especially Sikhs and Muslim. This is not an entirely new phenomenon: in Britain and France, Muslim families, with a background in South Asia or North Africa, were already well-established in the 1970s, and a second generation (in France les beurs) was already evident in the early 1980s, if not before. But since the 1970s, the Muslim family presence in Europe (immigrants, refugees and their descendants) has become progressively wider and deeper, as well as more diverse in terms of origin. Hence, matters routinely affecting family life and relations of gender and generation have grown in importance with immigration and settlement catalysts for changing perceptions of self and others, forcing all parties (incomers and members of receiving societies) to reassess and perhaps reassert cherished values, and bringing individuals and families within the purview of the law.

Thirdly, although many are now long-term migrants, or born and brought up in Europe, relationships with societies of origin have not diminished. As a huge literature has shown, information and communication technologies and cheap air travel enable migrants to maintain significant social, economic and cultural ties with countries of origin, and with fellow migrants elsewhere. Transnationalism or rather the transnationalization of relationships, is a major factor in the contemporary scene, with the consequence that the world of migrants, refugees and settled minorities is often multi-jurisdictional and trans-jurisdictional not least where marriage is concerned (Shah 2010a, 2010b; Sona 2014). An annual report of the Office of the Head of International Family Justice for England and Wales, for instance, noted that the movement of people across borders has brought before the courts ‘an increasing number of family law cases with an international dimension’ (2013: 23).

Fourthly, some people from such backgrounds may seek to maintain some practices seemingly at odds with those of the societies in which they have settled and are therefore perhaps ‘problematic’ so far as the law and public policy are concerned. I emphasize some, and add that legal issues may arise as a result of what is occurring within minority6 families, in the changing dynamics of gender and generation in demographically maturing populations (Qureshi et al. 2012; Werbner 2004), as much as from any disjunction between minority and majority practices, though the two are directly or indirectly connected. There are, certainly, many cultural and psychological assumptions (for example regarding the best interests of children or the status of women) hegemonic in contemporary Western societies but different from those prevailing in other cultures, and this disjunction may be a cause of much anguish on all sides. But ‘Western’ cultural/psychological assumptions have now to a large extent ‘gone global’ and permeate legal and normative templates in many parts of the world with implications for the internal relations of families of non-Western origin.

Fifthly, we are in what the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas (2008) has called a post-secular world, with people increasingly turning to religion to guide their conduct and seek advice on how to comport themselves in societies often seen as secular, individualistic and immoral. This may seem paradoxical given that the 2011 UK census, for example, showed a decline in belief and practice among adherents of the historic Christian churches (see also Park et al. 2013), with the former Archbishop of Canterbury (Rowan Williams) describing Britain as a ‘post-Christian’ society.7 Against that there has been a rise of new forms of Christian religiosity (the evangelical movement, the Black majority churches and so on), along with new forms of spirituality, and the increasing visibility of non-Christian faiths, including Hinduism and Sikhism. The turn to religion, locally and globally, is certainly noticeable among Muslims for whom Islamic law and practice, as enshrined in the Qur’an and in the traditions associated with the sayings and acts of the Prophet Mohammed, and their various interpretations (Shari’a) constitute, it is claimed, an imperative guide to moral conduct. A follower of Islam has many identities besides a religious one (gender, class, ethnicity, age, nation and so on), and analytically it may be misleading to treat religion as defining a person’s subjectivity (Alexander et al. 2013), thereby reproducing the categories of current political or religious rhetoric, and ignoring other, more significant ways of constituting identities. Nonetheless, for some people (outsiders, insiders, Muslims, non-Muslims) a person’s essence is captured by their religion; being a Muslim (or Christian or Jew) is crucial to their lived experience.

Sixthly, that Muslim migrants and their descendants reside in Muslim minority countries has given a new urgency to long-standing questions concerning followers of the faith living outside of the ‘abode of Islam’ (Moore 2010; Sardar-Ali 2013a, 2013b, and references cited). Should such places be treated as hostile territory, the ‘abode of war’, or regions where one may live peacefully and compromise is possible? In this connection, there has been a proliferation of claims (for example by Muslim scholars operating internationally and supported by countries such as Saudi Arabia) concerning the recognition of Shari’a (or ‘Muslim legal and ethical norms’, Maleiha Malik, 2009), and its availability for Muslims living in Muslim minority countries. Sometimes couched in the language of a traditional, puritanical, ‘Salafist’ form of Islam (Cesari 2013; but see Bowen 2014 for other variations), these claims go way beyond the cautious search for a ‘place’, that perhaps characterized an earlier epoch (Joly 1988), posing questions about the role of Islam in public life, and the nature of citizenship. What does it mean to be a citizen of Britain and so on and a Muslim; what kind of a citizen can/should a Muslim be? Might devout Muslims make concessions to the laws of the land, and adapt Islam to the local context? To what extent is Shari’a open to reinterpretation and modification via ijtihad (independent reasoning) when some Islamic scholars argue that this debate was closed centuries ago? These have become pressing issues within minority institutions and associations, and not least among families whose members are reflecting on how to manage affairs in a changing world where relations are ever more complex and less clear-cut, and kin are widely dispersed across geographical and socio-cultural space.

Seventh, while such matters exercise many Muslims, they also concern non-Muslims reflecting about Islam in the West. The changing nature of the Muslim presence along with the globalization and transnationalization of a resurgent Islam, and a deepening crisis of trust between Muslims and non-Muslims, on both sides of an apparently widening divide, especially after 9/11, have led to a questioning of policies of multiculturalism. From c. 1960–2000, Britain sought to control and regulate immigration while accepting that most immigrants were here to stay. There was increasing recognition of the legitimacy of cultural difference, allowing the expression of such difference, within certain limits, in the private sphere, and to some degree the public sphere too. Moreover, a raft of legislation enacted from the 1960s through to the mid-2000s addressed the rights of minorities, enhancing their ‘freedom from’ (to use Isaiah Berlin’s terminology, 2002), for example, discrimination.8 After the turn of the millennium, however, there was a ‘backlash’ against such policies (Vertovec and Wessendorf 2010). Countries such as Britain were seen as becoming ‘too diverse’ (Goodhart 2004), with an ‘excess of alterity’ (Grillo 2007a).

Claims by opponents (philosophers, politicians, religious leaders, among others) that multiculturalism encouraged separatism and radicalization and threatened social cohesion were seemingly justified by disturbances in the ethnically mixed cities of northern Britain in 2001 which occasioned heart-searching about the alienation of young Muslims. A review of the disturbances led to the conclusion that ‘many communities operate on the basis of a series of parallel lives’(Cantle Report 2001: 9), and that Britain was ‘sleepwalking to segregation’, as Trevor Phillips, then Chairman of the Commission for Racial Equality, controversially put it,9 a view contested by Finney and Simpson (2009). Both phrases achieved widespread currency. Moreover, practices seemingly at odds with those of Western societies were increasingly deemed unacceptable in societies espousing liberal, democratic, individualistic, secular values. Especially when associated with Islam they attracted ever-growing media attention (Moore, Mason and Lewis 2008), and were central to arguments about the rights and wrongs of ways of living in multicultural societies in Europe and elsewhe...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Acronyms

- 1 Cultural Diversity and the Law

- 2 The Spectre of Shari’a

- Part I Politics and the Muslim Family

- Part II Baroness Cox’s Bill

- Appendix

- References

- Index of Cases Cited

- Index