- 302 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

On South Bank: The Production of Public Space

About this book

Tensions over the production of urban public space came to the fore in summer 2013 with mass protests in Turkey sparked by a plan to redevelop Taksim Gezi Park, Istanbul. In London, concomitant proposals to refurbish an area of the 'South Bank' historically used by skateboarders were similarly met by staunch opposition. Through an in-depth ethnographic examination of London's South Bank, this book explores multiple dimensions of the production of urban public space. Drawing on user accounts of the significance of public space, as well as observations of how the South Bank is 'practised' on a daily basis, it argues that public space is valued not only for its essential material characteristics but also for the productive potential that these characteristics, if properly managed, afford on a daily basis. At a time when policy-makers, urban planners and law enforcement authorities simultaneously grapple with pressures to deal with social 'problems' (such as street drinking, vandalism, and skateboarding) and accusations that new modes of urban planning and civic management infringe upon civil liberties and dilute the publicity of 'public' space, this book offers an insightful account of the daily exigencies of public spaces. In so doing, it questions the utility of the public/private binary for our understanding both of common urban space and of different sets of social practices, and points towards the need to be attentive to productive processes in how we understand and experience urban open space as public.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access On South Bank: The Production of Public Space by Alasdair J.H. Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

In recent times, public space has gone from being treated, in planning and academic discourse alike, as the space between buildings of secondary importance to built structures themselves (after Gehl 1996) to being the singular focus of professional conferences (for example Universal Design 2012, see http://www.ud2012.no/) and a key part of large-scale regeneration strategies (most famously the regeneration of Barcelona at the turn of the twentieth century [for example Blanco, Bonet and Walliser 2011]). Paradoxically, it is precisely at a time that commentators assert we are seeing ‘multiple closures, erasures, inundations and transfigurations of public space at the behest of state and corporate strategies’ (Smith and Low 2005: 1) that ‘public space’ is coming to the fore as a valid design subject in and of itself. This book attempts to explore this tension through an ethnography of a prominent set of public spaces in central London, ‘the South Bank’, conducted during a lengthy phase of physical transformation of that area. In doing so it identifies the productive qualities of space – a sense that it is always ‘in the making’ – as core to its publicness.

As city centres and their constituent public spaces are revisited and transformed in the current ‘global era’ of city-building (Herzog 2006), the observation has been made that until recently academic ‘work on the transformation of public space in contemporary cities was not based on empirical research that took into account the everyday experience of different social groups in that space’ (Degen 2001: 3 [emphasis in original]). For the purposes of this book, I would like to take this argument a step back: it is not only socio-spatial practices in public spaces subject to physical and/or functional transformation that have been neglected in empirical research, but rather empirical studies of socio-spatial practices in urban public spaces per se are lacking. Whilst key policy documents (especially The Value of Public Space [CABE Space 2004] and the Urban White Paper [DETR 2000] in the UK context) have stated the ‘vital’ contribution of ‘public open spaces … to the quality of urban environments and the quality of our lives’ (DETR 2000: 74), empirically-informed research into this relationship is limited so far.

The aim of this research, therefore, is to generate a qualitative understanding of the use, management and production of a particular set of urban public spaces as a means to explore the ‘value’ of public space presupposed by such policy literature. In line with the remit of the ‘re-materialising cultural geography’ series of which the book is a part, the study constitutes an empirically driven attempt to explore, through the analysis of the concomitant use and redevelopment of a particular public space setting, the dialectical relations which exist between culture, social relations and space and place. Given the onus of the series on revisiting the material contexts of culture in human geographical accounts, the book is also driven by a methodological concern, elaborated in the next chapter, about the need to address Mitchell’s (1996: 130) lament that researchers interested in urban spaces putatively provided for public consumption often ‘discount the experience of so many users of these spaces’.1 In particular I am interested in the ways that the open spaces of the South Bank are, more or less consciously, produced through architecture and urban design, through re-branding exercises and institutional prescriptions of function, and through use and everyday social production. It is on this broad production process that the analysis that follows comes to focus.

South Bank as a Case Study

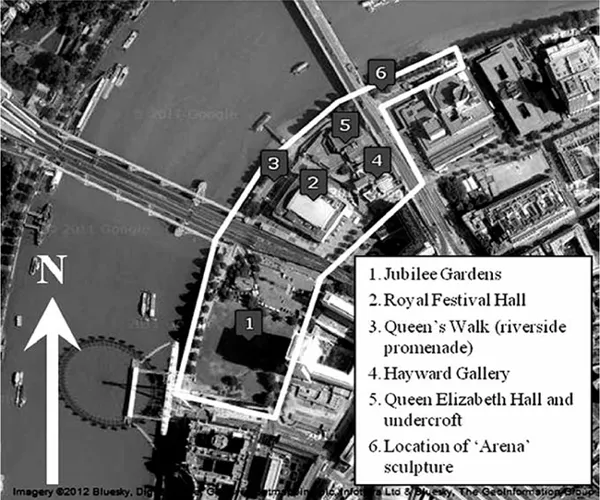

My hope for this text is that it provides a close account of the public life of the open spaces surrounding the Southbank Centre assemblage of arts institutions on the south embankment of the River Thames in central London (see Figure 1.1).2 While recent studies of urban public life have often employed a comparative approach (for example Anderson 1990; Cybriwsky 1999; Degen 2008), this research better resembles an ‘intrinsic case study’, whereby ‘in all its particularity and ordinariness, this case is itself of interest’ (Stake 1998: 88). Thus, the historical development of the Southbank Centre (and most notably the specific [ultra-]modernist ideological premises guiding its conception as the site of the ‘Festival of Britain’, May-September 1951)3 cannot be circumscribed without adversely affecting the salience of the findings generated. For example, if the Royal Festival Hall – the only part of the Southbank Centre remaining from the Festival of Britain – was intended as ‘a new sort of democratic cultural centre’ (McKean 2001: 4), then to ignore such intentions in a study of the social life of the surrounding area would clearly diminish the value of any conclusions drawn. Significantly, it is precisely these post-war origins of the ‘South Bank’ that are being re-appropriated in the ongoing redevelopment of the Centre.

Figure 1.1 Aerial photograph of South Bank

In addition, the Southbank Centre’s development has been temporally, and to some extent aesthetically, disjointed. Thus, a 17 year gap exists between the construction of the earliest (Royal Festival Hall 1951) and most recent (Hayward Gallery 1968) arts venues now constituting the Centre. Critically, this rather ad hoc ‘approach’ to urban design – as Matarasso (2001: 35) puts it the Centre’s ‘landscaping … emerged by default from a succession of unconnected “improvement” initiatives’ – contrasts the stylistically and ideologically integrated ‘masterplanning’ approaches now advocated for large scale projects in the urban design literature (see Sennett 2004: 3). Rather than avow and physically portray coherence from the outset, the Southbank Centre as a retrospectively assembled set of cultural institutions has had an ambiguous spatial and institutional identity. Moreover, this ambiguity relates not only to the Southbank Centre, but is definitive of the broader South Bank, an area that Minton (2006: 33) identifies as a ‘patchwork’ of publicly and privately owned and managed spaces. In a similar vein, Newman and Smith (2000: 12–15) identify the South Bank as a zone of mixed commercial and publicly-funded activity ‘interspersed with … [a] string of visitor-related sites that are united for the most part by the Thames Trail along the riverside’ (Newman and Smith 2000: 14). This spatial indistinctiveness is heightened because both the South Bank, and the Southbank Centre estate itself, straddle the London Borough boundary between Lambeth and Southwark.

At this point, the significance of the timing of the research on which this text is based must be acknowledged. Thus, while the social consequences of urban regeneration are by no means the sine qua non of this book, the time-frame for data collection is one characterised by change rather than stability. That is, on the one hand the Southbank Centre has been subject to its own redevelopment masterplan (by Rick Mather architects) since 1999. This ‘transformation’ (as the Southbank Centre administration describe it [SBC 2004]) has been organisational as well as material, as the Centre’s 2007 re-branding (from ‘South Bank Centre’ to ‘Southbank Centre’) attests. At the same time, and at a number of scales, other sites, districts or clusters along the South Bank have also had their identities strengthened and their ‘locatedness’ brought into sharper relief. For example, the public realm around the Royal National Theatre adjacent to, but not formally part of, the Southbank Centre was regenerated not so long ago (in particular with the Lottery-funded creation of ‘Theatre Square’ in 1998). At the district scale, since their formation in 1991 the South Bank Employers Group have taken an increasingly active role in ‘physically improving’ and ‘marketing’ the local area, and in promoting a coherent visual identity for it (esp. SBEG 2004). This particular (SBEG) realisation of the ‘South Bank’ has been complemented by the emergence of ‘Better Bankside’ in 2004, a Business Improvement District (BID) responsible for the section of the ‘South Bank’ east of SBEG (and up to London Bridge). In this respect, my research comes at a time when, as Anna Minton (2006: 33) puts it:

[I]t is clear that the pattern of [management] is changing and moving as Adam Caruso notes from ‘density of ownership’ to the single ownership of areas. The result is that the South Bank can now be clearly divided into chunks or enclaves which have a clearly defined feel from one another.

That is, this book describes a moment when the ‘ambiguity’ or openness of the South Bank is being challenged not so much by changing ownership per se, but by a realisation of space by a number of organisations and institutions and at a number of scales.

With this in mind, the discussion that follows to some extent pertains to relatively stable visible forms and social relationships as they respond (either directly or indirectly) to physical and managerial change. However, the pervasiveness of these changes is again key. Given the scale of the Southbank Centre’s ‘transformation’ (170,000 m2) and its emphasis on renovation rather than wholesale (re)creation, the morphological change taking place is again piece-meal. Some aspects of the ‘transformation’ are complete (for example the Hayward Gallery ‘pavilion’ designed by Dan Graham and Haworth Tompkins Architects [2003], the RFH’s ‘Festival Riverside’ frontage and ‘Liner Building’ designed by Allies and Morrison Architects [2004 and 2005 respectively], and the Jubilee Gardens re-landscaping by West 8 Landscape Architects [2012]) or under consideration (for example the ‘refurbishment of the Queen Elizabeth Hall undercroft’ [SBC 2006: 5; also Escobales 2013] and redevelopment of the Hungerford car park site). This timing allowed for an analysis not only of everyday practices in social space, but also an analysis of these practices as they were mediated by periods of intensive morphological change.

My attention to the South Bank also has a personal basis, and here Walter Benjamin’s (1999: 262) observation that ‘[t]o depict a city as a native would calls for … the motives of the person who journeys into the past, rather than to foreign parts’ seems salient. That is, I developed a particularly strong lay relationship with the South Bank when I started skateboarding there on a weekly basis in ca. 1993 (until 1999). The extended (30 year plus) toleration of skateboarding by the Centre, and specifically of skateboarding in public space with the exogenous social interactions this engenders, suggested something to me about the specific character of the open spaces of South Bank. It is the social intricacies and minutiae of this character that I wanted to explore.

Defining ‘Public Space’ For This Research

It is important that I clarify at the outset what I intend by the term ‘public space’. Specifically, by emphasising the material dimension of public space in this research I aim to distance the empirical basis of this work from, firstly, more abstract fields of enquiry (esp. the Habermasian notion of the ‘public sphere’ [for example Benhabib 1992]). At the same time, however, I want to avoid overly spatial definitions of public space as material surface; definitions of public space simply as ‘the green spaces, parks, streets, civic squares and other outdoor spaces that are freely accessible to the public and usually free of charge’ (CABE Space 2007a: 12). Spatial typology-based definitions such as these arguably preclude the ways that spaces are experienced as public, and their conceptualisation as spaces produced as much through everyday practices as design.

The following analysis therefore partly sits in opposition to attempts at prescriptive definitions of public space and is interested instead in what it is about socio-spatial practice on the South Bank that means it is understood as ‘public space’. As a framework for this highly contextual understanding of ‘public space’ it is, however, worth situating the concept in a relational way. This approach is adapted from Lyn Lofland’s (1998) overview of social scientific research in this field: The Public Realm: Exploring the City’s Quintessential Social Territory. Here, the work of Albert Hunter (1985, in Lofland [1998: 10–15]) is particularly useful. Hunter develops a triptych of the ‘realms’ of city life, in which some important distillations are made. Hunter’s three realms are as follows:

• The private realm characterised principally by intimate ties between primary group members located within households/personal networks.

• The parochial realm characterised principally by a sense of commonality among those involved in interpersonal networks that are located within communities (for example intra-neighbourhood or intra-workplace relations).

• The public realm ‘constituted of those areas of urban settlements in which individuals in copresence tend to be personally known or only categorically known to each other’ (Lofland 1998: 9 [emphasis in original]).

In articulating this triptych, Lofland’s (1998: 22) own distinction between ‘public space’ and the ‘public realm’ is also clearer; for Lofland (1998: 11), realms ‘are social, not physical territories’. As such, the co-ordinates of the public realm are not necessarily invariable, and do not (and moreover cannot) map precisely onto the geometric bounds of legally public space. Rather, in categorising a particular space, the nature of the social relations present (and the scale and intensities of these relationships) is deemed important. For example, in William F. Whyte’s (1981) seminal study of mid-twentieth century ‘streetcorner society’ in an Italian slum in Boston, it is clear that (at least at certain times) the streetcorners described, though legally ‘public’ spaces, constitute the parochial realm. Conversely, a cinema foyer before or after a screening, while constituting a ‘private space’ in legal terms, might house activity more characteristic of the public realm.

In this respect, the intricacies involved in the particular reading and usage of the term ‘public space’ adopted here surface; that is, I am interested in an empirically-grounded understanding of a particular set of material spaces that are open to the public. Here it is worth noting that, in legal terms, the Southbank Centre (since the appointment of a South Bank Centre Board in April 1987 [Matarasso 2001: 24]) is an independent and privately-managed complex, and so should perhaps most accurately be termed a ‘publicly-accessible property’ (esp. Staeheli and Mitchell 2008).4 However, it is also a set of institutions and spaces that is run on behalf of the public and receives public funding.5 This complex ownership and management structure, which undoubtedly exacerbates the sense of ambiguity (of ‘publicity’, ownership and spatial extent) experienced at the site, has been set out in the ‘memorandum submitted by the South Bank Centre’ to the Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport (House of Commons Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport 2002a) for their third report on ‘Arts Development’. This memorandum states that:

The South Bank Centre is a charity that manages a 27-acre estate from County Hall to Waterloo Bridge …, on a long lease from the Arts Council, who hold the freehold on behalf of the Government in the form of Department of Culture, Media and Sport. The estate is comprised of arts buildings and substantial public realm …. The British Film Institute, an independent organisation that is a subtenant of the South Bank Centre, manages the National Film Theatre under Waterloo Bridge and the IMAX cinema in the Waterloo roundabout. The South Bank Centre’s public realm comprises Jubilee Gardens, Queen’s Walk from the County Hall to the Royal National Theatre, as well as important commuter pedestrian routes from Hungerford footbridge … and two major service lanes and delivery yards. In the spring of 1998 the Department of Culture, Media and Sport … charged [Elliot Bernerd, then Chairman of the South Bank Centre, with … ] the responsibility of working with all stakeholders to bring the arts complex up to world class standards with £25 million of Arts Council lottery funds and further funding from the Heritage lottery Fund. … Taken together with the independently managed Royal National Theatre and the British Film Institute, the centre represents the largest concentration of cultural facilities anywhere in the world.

Given these complexities, in the analysis that follows ‘the importance of reconceptualising publicity and privacy in ways that separate the content of actions from the spaces in which action is taken’ (Staeheli 1996: 601 [emphasis in original]) becomes clear. The formal ‘privacy’ of the Southbank Centre in terms of ownership does not therefore necessar...

Table of contents

- Cove Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Public Space as a Research Setting

- 3 Boundary Effects: Morphology and Activity at South Bank

- 4 South Bank as Theme Park? Public Space and the Practical Accommodation of Disorder

- 5 Play and Public Space: Theorising Ludic Practices at South Bank

- 6 ‘The Stamp of the Definitive’: From ‘Loose Space’ to ‘Public Realm’ at South Bank

- 7 Conclusion: Time to Stand Back? The Reinvented Southbank Centre

- Bibliography

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Index