- 374 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Psychoanalytic Geographies

About this book

Psychoanalytic Geographies is a unique, path-breaking volume and a core text for anyone seeking to grasp how psychoanalysis helps us understand fundamental geographical questions, and how geographical understandings can offer new ways of thinking psychoanalytically. Elaborating on a variety of psychoanalytic approaches that embrace geographical imaginations and a commitment toward spatial thinking, this book demonstrates the breadth, depth, and vitality of cutting edge work in psychoanalytic geographies and presents readers with as wide a set of options as possible for taking psychoanalysis forward in their own work. It covers a wide range of themes and perspectives in terms of theoretical approaches such as Freudian, Lacanian, Kristevan, and Irigarayian; conceptual issues such as space, power, identity, culture, political economy, colonialism, ethics, and aesthetics; disciplinary insights including Geography, English, Sexuality Studies, and History of Science; as well as empirical contexts such as the reception of psychoanalysis in early twentieth century England, psychoanalytic geographies of violence and creativity in a small Mexican city, visual cultures of second-generation Iranian artists living in Los Angeles, and the hysterical underpinnings of climate change scepticism.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

Histories and Practices

Chapter 1

Freud in the Field: Psychoanalysis, Fieldwork and Geographical Imaginations in Interwar Cambridge

A great wave of enthusiasm for psychoanalysis had struck the University of Cambridge. Arthur George Tansley, having resigned from the Cambridge Botany School in 1923 to study with Freud in Vienna, was one of the chief fomenters. This was a productive moment for psychoanalytic applications in numerous fields and key insights in economics, psychology, English, and anthropology can be traced to Freudian inspiration (Forrester and Cameron forthcoming). Can we say the same for the discipline of geography in its Cambridge context? On the face of it, the answer seems a pretty safe “no.” After “generally lamentable beginnings” with the first lecturer Henry Guillemard resigning when pressed to actually lecture (Stoddart 1989: 25), the early teaching focus was physical geography. Founding figures of Cambridge geography like Antarctic scientist Frank Debenham and historical geographer H.C. Darby (the first PhD in 1931) exhibited little interest in psychoanalysis.

And yet, one of the first people to introduce psychoanalysis to Cambridge students was Tansley who taught plant geography in the Natural Sciences Tripos and in the Geographical Tripos during the height of psychoanalytic fervor. The father of Tansley’s psychoanalytic colleague, James Strachey, was Sir Richard Strachey who had been integral, as President of the Royal Geographical Society, in the establishment of the first lectureship in geography at Cambridge in 1888 (Stoddart 1989: 24). Such details are just beginnings to the story. Drawing from a larger study, Freud in Cambridge, this chapter considers the reception of psychoanalysis amongst Cambridge staff and students in the years before and after the Great War, and argues that geographical methods and concepts taken for granted by contemporary researchers such as “participant observation” and the “ecosystem” have, if not direct links to psychoanalysis (and Cambridge geography), collateral descent.

Besides unearthing some new kin for present day psychoanalytical geographers, this chapter diverges from a standard history of psychoanalysis in at least two important ways. First, in departing from the historiography of British psychoanalysis centering on London and the institution-building work of Ernest Jones, our story involves a non-standard cast of characters, including non-professional psychoanalysts. Secondly, in locating psychoanalytic interest in a key center of the natural sciences we defamiliarize the present understanding that psychoanalysis belongs within the realm of culture, a tool of the human geographer only. Our story is a jolting reminder of a time when psychoanalysis was also recognized as a science, when it was a marker of scientific modernity to be psychoanalyzed and when a dream, as a matter of course, had the serious potential to change an academic’s life.

Cambridge Before and After the First World War

Geography made its disciplinary debut at the University of Cambridge in 1888. With funds from the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), the university appointed a lecturer in geography. In order to illustrate what that lecturer, once selected, should be teaching, the new RGS President, Sir Richard Strachey, delivered four public lectures on “Principles of Geography,” dealing mainly with “external nature” and drawing on his considerable knowledge of physical geography and the history of geography. However, he also referred to nature’s influence on the development of “man’s emotional, intellectual, and moral faculties” (Strachey 1888: 290).

A knowledge of the relations that subsist among living beings, which is a direct result of geographical discovery, shows us man’s true place in nature; our intercourse with other races of men in other countries teaches those lessons needed to overthrow the narrow prejudices of class, colour, and opinion, which bred in isolated societies, and nourished with the pride that springs from ignorance, have too often led to crimes the more lamentable because perpetrated by men capable of the most exalted virtue.

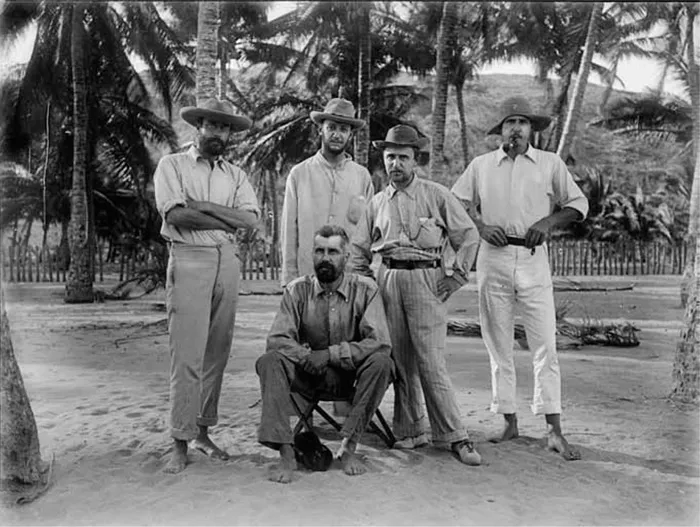

Figure 1.1 Some members of the Torres Strait Expedition: Haddon (seated) with (l–r) Rivers, Seligman, Ray, and Wilkin. Mabuiag, 1898

Source: Reproduced by permission of the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (N.23035.ACH2).

Although physical geography was strongly emphasized, geography teaching early on included the subject of anthropogeography (the scientific study of human geographical distribution and relationship to environment) taught for two decades by Alfred Cort Haddon, himself a member of the Royal Geographical Society from 1897 (RGS 1921).

Famously, Haddon (see Figure 1.1) led the 1898 Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to the Torres Straits. The event was formative for Cambridge and British anthropology, involving the development of field methods, with Haddon at this time introducing to anthropology the standard geographical survey term “field-work” (Herle and Rouse 1998: 17; in geographical usage, see, for instance, Pringle 1893: 139). His companions included W.H.R. Rivers, a Cambridge psychologist who would find his interests diverted to anthropology through the experience, and C.S. Myers, a former student of Rivers’s who would later share Rivers’s interest in Freudian psychoanalysis. Another was Charles Seligman, member of the RGS from 1906, whose subsequent fieldwork would also involve studies of dreams and the unconscious. Funded mainly by the university with smaller donations from the RGS and other societies (Herle and Rouse 1998: 58), Haddon envisaged the expedition as a “multidisciplinary project encompassing anthropology in its broadest sense” (ibid.: 3) and, once safely returned, Haddon provided the RGS with a public demonstration of film, phonograph recordings and lantern slides from the expedition (ibid.: 129) and would seek from its members continued support for further investigations in Melanesia (Haddon 1906). For Rivers, the Cambridge Torres Straits Expedition had initially been a project in comparative psychology, yet his intensive methods led him to address and resolve problems in anthropology and geography. The soberly qualified psychological findings were most straightforwardly interpreted as demonstrating little if any difference between the perceptual capacities of white Europeans and Torres Strait Islanders. These probably did form the starting-point for the anti-racism or non-racism, particularly of Rivers and Myers, and thus demonstrated a clear-cut estrangement from the evolutionist assumptions of Victorian anthropology (Richards 1998: 136–57, 1997).

Teaching virtually ceased during the war of 1914–18 as Cambridge became a site for regiments to be drilled and housed, and libraries were transformed into hospitals. Rivers turned immediately from ethnography to the treatment of the war neuroses, most famously those of officers at the Craiglockhart Hospital. In parallel with this activity, Rivers had been seized with scientific enthusiasm for Freud’s theory of dreams, his interest intensifying markedly as he worked on his own dreams (Forrester 2006: 65–85). Following the armistice, Rivers gave 19 lectures at Cambridge on “Instinct and the Unconscious,” published as a book of the same name in 1920. He also lectured on dreams; after his sudden death in June 1922, this lecture series was published by his literary executor Elliot Smith as Conflict and Dream (1923). Although in both books Rivers revealed himself in new and unprecedented ways, Conflict and Dream was especially revealing of Rivers’s internal world, since he followed Freud’s example in both spirit and letter in using principally his own dreams (with settings and associations from Cambridge furnishing significant aspects of the dream material) to examine critically Freud’s theory of dreams. As emboldened students like Harry Godwin “tried our hand at dream analysis and collected our own instances of the ‘Psychopathology of everyday life’” (1985: 30), Cambridge dreaming Freudian-style was in full swing.

Field Imaginations

The Making of Participant Observation

W.H.R. Rivers’s premature death in 1922 inflicted considerable distress on his students and friends. Rivers had lectured alongside geographers in Indian Civil Service Studies, but his specific contribution to the discipline of geography had much to do with his innovations in “intensive” field methodology. Haddon had been involved in “the intensive study of limited areas” (Herle and Rouse 1998: 15–16) before the 1898 expedition, but credit for the full development of participant observation is often ascribed to a transmission of thought and practice from Rivers to Bronislaw Malinowski.

Participant observation, in which the ethnologist herself becomes a research tool and has explicit interaction and involvement with those people being studied, figures prominently in human geography textbooks on method (for example, Clifford and Valentine 2003; Flowerdew and Martin 2005), yet, as to its origins, most geographers likely would suggest it is an example of recent interdisciplinary borrowing from anthropology. Furthermore, such texts do not link psychoanalysis to the history of fieldwork (though Ian Cook provides a suggestive passage in which he recommends recording dreams in a diary; Flowerdew and Martin 2005: 180). Indeed, if at all, Freud or psychoanalysis explicitly comes up in such methods textbooks only in relation to feminist and textual analysis. In this section, we highlight not only participant observation’s psychoanalytical connections, but also its more geographical associations through the work of Rivers.

There are two mythicized founding dates for social anthropology in Britain: the Torres Straits Expedition of 1898 and the publication in 1922 of both Malinowski’s Argonauts of the Western Pacific and Radcliffe-Brown’s The Andaman Islanders. The second of these dates also marks the aforementioned death of the leading anthropologist of the period 1898–1922: W.H.R. Rivers, whose career began with the Torres Straits Expedition. Another way of putting this is to claim that what was started in 1898—the intensive fieldwork approach to understanding “primitive” cultures—came to fruition with the publication of two monographs by practitioners who had learned the lessons of the Torres Straits program and put them into practice in the 1910s, and were thus as a consequence able to produce perfectly formed exemplars of intensive fieldwork and the understanding based upon it.

This account places all the emphasis upon method: that ideal of the lone researcher going out, immersing in one very specific native culture, becoming a “participant observer” (a mid-1920s term) and reporting back. Part of the eventual prestige of social anthropology would come to rest on the sheer arduousness of the labor involved and hardships undergone in this process and upon the fact that no other researchers were involved or had ever been there; the new fieldwork ideal was strangely solitary and naïvely empiricist in its conception of professional expertise. Yet there was an accompanying conceptual transformation in the period 1898–1922: where the center of gravity of anthropology had been evolutionism and religion, the new social anthropology was non-evolutionist (because synchronic structural-functionalist) and preoccupied with social structure and order. The key area for understanding social structure became “kinship,” investigated using the “genealogical method,” what Stocking calls the “the major methodological innovation associated with the Cambridge School” (1995: 112), developed in Rivers’s work with the Todas, the Solomon Islands, Melanesia, and Polynesia during the first decade of the twentieth century. A new ideal was promoted in the section Rivers wrote for the Royal Anthropological Institute’s updated 1912 edition of Notes and Queries (Urry 1972: 45–57) contrasting “survey work” with what was now required—“intensive work”:

A typical piece of intensive work is one in which the worker lives for a year or more among a community of perhaps four or five hundred people and studies every detail of their life and culture; in which he comes to know every member of the community personally; in which he is not content with generalized information, but studies every feature of life and custom in concrete detail and by means of the vernacular language (Rivers 1913: 7).

In these Notes, Rivers set out a “concrete” field methodology, giving license to the “model of the lone field ethnographer, ‘immersing’ himself in ‘the natives’’ way of life” (Buzard 2005: 9); Malinowski would bring these Notes to Papua New Guinea where he would conduct ethnographical fieldwork from 1915–18, receiving in addition detailed instructions from Seligman on how to “observe those facts relevant to Psycho-Analysis” (Malinowski unpublished) as well as “a short account of dreams” (Stocking 1986: 31). Alongside Rivers, Haddon and Myers, the chief contributor to the 1912 edition of Notes and Queries was the scholar of ancient geography, James Linton Myres, life member of the RGS since 1896. Following a section in which Myers and Haddon discussed the recording of emotions (“a snap-shot camera will be found invaluable”, Freire-Marreco and Myres 1912: 181) and gestures, Notes and Queries reprinted the RGS official scheme for the transcription of place-names (1912: 186–92). Myres provided instructions regarding geographical topics such as “path-finding,” “landmarks,” and “modes of travel” (98–101). At the same time as Rivers was preparing his “General Account of Method” for Notes and Queries, which suggested that native terms should be used whenever possible, he was also involved with Myres, Haddon, and Sydney Ray (the language specialist member of the 1898 expedition) in discussions with the RGS on the geographical nomenclature for the Melanesian Islands (Thurn et al. 1912: 464–8). Rivers’s formal presentation to the RGS in March 1911, illustrated with several specially prepared maps, was published in The Geographical Journal in May 1912 (Rivers 1912: 458–64). His critical examination of naming practice argued for the use of native names for practical and political reasons but stressed also the confusions that can result. Intense fieldwork in one area requires attention to geographical specificity as sometimes, for instance, a name for a local district might be the same name for the island as a whole. He appealed to the RGS, most sensibly in collaboration with Royal Anthropological Institute, to take action.

The modern movement in ethnology attempts to portray native institutions by giving concrete accounts of things as they are from the native point of view … Such a concrete method will come more and more into use in the future, but such concreteness can result in nothing but confusion unless native names, including those of places, are used in accurate and well-defined senses (459–60).

Though he mapped out the terrain of participant observation, Rivers never fully entered on it himself. Always aware of issues of objectivity and the interests of the observer, he stood on the verge of recognizing that the observer’s implication in the scene of inquiry was constitutive of the field of the human sciences. In the field of psychotherapy, he hoped to escape from Freud’s recognition that in both dreams and the neuroses, there was no avoiding the implication of the subject’s own desires and the observer’s relationship with his patients—indeed, this implication was being turned around by Freud into the foundation stone of the theory and therapy of the “transference neuroses.” As Buzard (2005: 9–10) astutely notes,

[A]uthority derives from the demonstration not so much of some finally achieved “insideness” in the alien state, but rather from the demonstration of an outsider’s insideness. Anthropology’s Participant Observer, whose aim was a “simulated membership” or “membership without commitment to membership” in the visited culture, went on to become perhaps the most recognizable (and institutionally embedded) avatar of this distinctively modern variety of heroism and prestige.

With Rivers’s sudden death, the program of rapprochement between psychoanalysis and anthropology that he had begun was unexpectedly transformed by his replacement as the intellectual leader of British anthropology by Bronislaw Malinowski who, despite his manifest and self-declared great debt to Freud, would later be recalled more for his rejection rather than incorporation of psychoanalysis on behalf of the discipline he did so much to professionalize. Both Rivers and Malinowski repeatedly acknowledged the “genius” of Freud; both Rivers and Malinowski mounted fierce critiques, based on their ethnographic expertise, of key features of psychoanalysis. Their contemporaries, for their own reasons, heard only the criticisms, not the admiration. Malinowski’s field diary from the Trobriand Islands (1915–18), published only in 1967, was no mere record of events but what he called “[a] location of the mainsprings of my life” (1967: 104, quoted in Stocking 1986: 23); it revealed his innermost feelings—fears, anger, love, sexual anxieties, and his dreams—and is best read as an “account of the central psychological drama of Malinowski’s life—an extended crisis of identity in which certain Freudian undertones were obvious to Malinowski himself” (Stocking 1986: 23). For Malinowski, following the ghost of Rivers, the novel method of participant observation required the observer to pass through the phases of participation and return, the going out and the coming back, capable of rendering that transmutation of his very being which he had undergone not only into objective data but also into a body of theory. The imperial side of the project was not new and nor was it given up by the new practitioners. What Malinowski added was a Freudian obverse, a requirement that the interior and the exterior be mapped onto each other.

Roots of the Ecosystem

The scene is Vienna, March 192...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface by Paul Kingsbury and Steve Pile

- Introduction: The Unconscious, Transference, Drives, Repetition and Other Things Tied to Geography

- PART I: HISTORIES AND PRACTICES

- PART II: PSYCHIC LIFE AND ITS SPACES

- PART III: THE TECHNOLOGIES OF BECOMING A SUBJECT

- PART IV: SOCIAL LIFE AND ITS DISCONTENTS

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Psychoanalytic Geographies by Paul Kingsbury,Steve Pile in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Movements in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.