eBook - ePub

John Adams's Nixon in China

Musical Analysis, Historical and Political Perspectives

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

John Adams's Nixon in China

Musical Analysis, Historical and Political Perspectives

About this book

John Adams's opera, Nixon in China, is one of the most frequently performed operas in the contemporary literature. Timothy A. Johnson illuminates the opera and enhances listeners' and scholars' appreciation for this landmark work. This music-analytical guide presents a detailed, in-depth analysis of the music tied to historical and political contexts. The opera captures an important moment in history and in international relations, and a close study of it from an interdisciplinary perspective provides fresh, compelling insights about the opera. The music analysis takes a neo-Riemannian approach to harmony and to large-scale harmonic connections. Musical metaphors drawn between harmonies and their dramatic contexts enrich this approach. Motivic analysis reveals interweaving associations between the characters, based on melodic content. Analysis of rhythm and meter focuses on Adams's frequent use of grouping and displacement dissonances to propel the music forward or to illustrate the libretto. The book shows how the historical depiction in the opera is accurate, yet enriched by this operatic adaptation. The language of the opera is true to its source, but more evocative than the words spoken in 1972-due to Alice Goodman's marvelous, poetic libretto. And the music transcends its repetitive shell to become a hierarchically-rich and musically-compelling achievement.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access John Adams's Nixon in China by Timothy A. Johnson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mezzi di comunicazione e arti performative & Musica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Setting the Scenes

Chapter 1

Portraits of the Chinese Landscape

The landscape of China was a new terrain to be discovered by Western viewers of President Richard Nixon’s historic visit in February 1972. Yet the inhabitants of this large, populous, ancient, and thriving civilization were well familiar with its agricultural contours, its colors, and its beauty. These perspectives on the Chinese landscape could not have been more different. Whereas its inhabitants saw fruitful soil, vivid colors, and serene openness, its Western visitors saw barren fields, a gray canvas, and emptiness. In Nixon in China, John Adams and Alice Goodman depict these differing perspectives of the Chinese landscape through Adams’s musical presentation as well as the ways in which the landscape is described in or implied by the libretto.

Adams foreshadows these conflicting points of view beginning with the opening measures that depict dawn on the day of Nixon’s arrival through overlapping ascending scales. With the simultaneous presentation of metrical and harmonic consonance and dissonance, Adams musically depicts this divergence in point of view between the American visitors and the Chinese citizens. The music that might be viewed as the overture – although the instrumental portion is not self-contained, nor particularly lengthy – contributes significantly to one of the main conflicts of the opera, the differing perspectives of East and West.

Goodman also establishes this conflict through descriptions of the landscape in the first scene. Looking at presumably the same fields, the Chinese citizens see potential, embodied in the fruits of their labor ready for harvest, but the Nixons fail to recognize this potential and see a vapid, vast, barren wasteland, as observed from their perspective, flying over from Shanghai to Peking (in Wade–Giles), now known as Beijing (in Pinyin). Finally, the opera ends with another view of the Chinese landscape, this time through the eyes of Premier Chou En-lai as he awaits dawn on his balcony on the last day of Nixon’s visit. In this way the opera both begins and ends at dawn, with alternative perspectives on both its colors and its significance.

The Red Dawn

As the opera begins, dawn breaks over China. While pedal tones alternate between A and F in the bass, calm ascending A aeolian (or natural minor) scales depict the rising of the sun, as shown in Example 1.1. The rhythmically overlapping orientation of these scales and their metrically dissonant placement undermine this morning calmness. However, the regularity and smoothness of the scales and the open textural spaces created between the different orchestral layers create a warm, hopeful, open feeling. Each scale appears in evenly spaced notes, but these layers either move at different rates or occur in metrically offset locations. As shown in the right hand of the piano reduction, the violins and violas present even eighth notes, articulating the two–two meter. Meanwhile, as shown in the smaller upper staff, the same A aeolian scale appears in dotted quarter notes in the trumpets (supported by piano 2), while even slower-moving scales appear in the English horn (supported by the left hand of piano 1) and the clarinets. The notes of these longer scales in the woodwinds occur in the equivalent of dotted half notes offset from each other, creating displacement dissonances against the other voices and each other.

Example 1.1 The instrumental opening of the opera (I/i/1–22)

LISTENING EXAMPLE: CD-1, t-1

The different layers present the potential for metrical grouping consonance, based on scale completion, which may be labeled as G48/24/8 (1 = eighth note) or G6/3/1 (1 = a measure). However, grouping and displacement dissonances, and their combination, foil the potential for metrical consonance among the three layers. The fastest layers, strings and trumpets, present a grouping dissonance of G8/3 (1 = eighth note), because the strings complete their scale every eight eighth notes, and each note of the trumpets’ scale lasts for three eighth notes. The two slower moving lines complete the scale every six measures, but misalign metrically with the other layers and with each other. Patterns of D6 + 4 (1 = eighth note) displace these scales against each other, because each note of the scale lasts six eighth notes, and because the English horn enters on the fourth eighth note of the measure while the clarinets enter four eighth notes later on the last eighth note of the measure. Meanwhile, different metrical dissonances, D8 + 3 for the English horn and D8 + 7 for the clarinets (1 = eighth note), displace these woodwind scales against the two faster moving scales. Through these metrical dissonances that occur throughout the opening in various ways, Adams foreshadows the conflict between Western and Chinese thoughts and ideals that will be featured in the opera and in the political talks that took place during the visit.

As a result of these metrical dissonances, rhythmic alignment occurs only between the fastest two layers, or G3/1 (1 = a measure) every three measures based on metrical grouping. However, the woodwinds never fall into alignment with the other voices, because they begin their scales in the middle of the measure (on the fourth eighth note and the last eighth note of every six measures), even though they share a consonant rhythmic grouping structure. Nevertheless, Adams’s use of identical scalar material in each of the four layers lends a familiar diatonic harmonic consonance to this opening section of the opera, despite the more subtle metrical dissonances. However, four-note staccato outbursts in the trombones interrupt the flow and upset the balance of the opening scene by their contrasting style as well as their metrically dissonant placement against the metrical structure of the other layers.

The pedal notes in the basses do little to solidify the metrical structure. At first the lower strings (shown in the left hand of the piano reduction in Example 1.1) alternate between A and F, but these strong moves do not coincide with any of the other scalar patterns in a consistent manner, appearing in the rhythmic pattern 20–13–12–10 (1 = quarter note), before the pattern of pedal notes changes. As the scalar material continues, an additional pedal bass note, C, increases the repertory of bass notes, first entering in a metrically weak position on the last eighth note of the measure (I/i/19) – with measures identified by (act/scene/measure). Meanwhile, higher pitched long notes begin to appear in the saxophones (I/i/15–30), earlier foreshadowed in the right hand of piano 1 of the orchestra, filling out the diatonic palette of longer tones and adding to the diatonic saturation in the scalar figures. Eventually, as shown in Example 1.2, the four-note staccato trombone figures begin to pair the initial note A with C (I/i/26–30), mirroring the basic motivic outline of the bass layer, and the outbursts become more persistent. The emphasis on the note C in pedal bass notes, upper-voice pedal notes, and staccato trombone interruptions set the stage for the first diatonic shift in the opera, through a motion that is locally dissonant but from a broader view becomes one of the most central harmonic relationships in the opera.

The A aeolian scales over an F major chord, as established by the F pedal bass and its arpeggio through the A and C of the staccato trombones, give way to C# aeolian scales and C# pedal tones (I/i/31). The lack of common tones, as well as the sudden appearance of a new diatonic collection, reflects the harmonic dissonance of this motion. However, taking a larger-scale view of this move reveals a more consonant relationship. PL transforms the A minor orientation of the opening passage to the C# minor orientation of this ensuing passage. As shown at the bottom of Example 1.2, the P part of the transformation occurs immediately, as C# replaces C on the first beat of the measure (I/i/31), whereas the L part of the combination occurs slightly later, as G# replaces A in the ascending scales that follow. This combination transformation maintains one common tone while the other two notes of the triad move parsimoniously (by the smallest possible distance) in opposite directions by a half step, C to C# and A to G#. In this way Adams simultaneously evokes the dissonant relationship between adjacent chords on a local level, moving between F major and C# minor based areas by major third (enharmonically) with no common tones, and a more consonant relationship on a larger scale, moving between two minor-triad based areas (A minor and C# minor) by parsimonious voice-leading. Furthermore, Adams also contrasts the dramatic shift between diatonic collections – with only three common tones between the two collections and no common tones between adjacent triads, but with a virtually identical presentation of rhythmically overlapping aeolian scales in the two diatonic collections. By these combinations of dissonant and consonant elements, the opening of the opera evokes a sense of the divergent views of the red skies of dawn breaking over the Chinese landscape in a purely musical way.

Example 1.2 Interaction of pedal notes and staccato trombones; large-scale motion to C# minor via PL (I/i/26–31)

The White Fields

The opera also portrays the landscape of China from two opposing views through parts of the libretto as well as the music that sets it. In the second section of the opening chorus, the Chinese citizens celebrate the value of the common laborer. They see white fields ready for harvest, symbolizing a country full of potential, and the red dawn shining brightly on the surrounding mountain ranges of their beautiful country. On the other hand, Richard and Pat Nixon see only a colorless, poor, barren landscape. Looking at the same view as the Chinese citizens, the Nixons’ view of China seems tainted by their Western eyes, and they fail to see the beauty and bounty of the land.

Recalling his flight from Shanghai to Peking as an American journalist about to cover Nixon’s historic landing at the airport, Theodore White recorded his impressions of the Chinese landscape and especially how it compared with his earlier memories of what he saw flying over China during World War II:

Below: the unmistakable mark of the revolution – roads. Roads linking village to village, to town and to city; thirty years before, paved roads faded to dirt tracks twenty miles out of most major cities. Furrows: the peasants had worked their fields, years before, in garden patches, some as small as two or three acres – now the furrows of the collective farms stretched longer than the farms of Iowa. Water reservoirs: heart-shaped embankments cupping life-giving water, irrigating villages once permanently parched. And trees – trees in China! – lining roads. (White 1973, vii–viii)

Whereas the Nixons saw only stark and barren fields, White, traveling over the same countryside, but with the wisdom afforded by his previous experiences, saw an active and well organized agrarian civilization.

Musically, Adams brings out contrasting perspectives of the landscape through harmonic and motivic means. With a minimalist surface, repetition depicts both viewpoints. However, whereas the dawn chorus of the Chinese people follows their repetitive passage with a wide-ranging palette of harmonic colors that rises up from the low register of the repetitive passage, Nixon follows the repetitive monolog of his travels with a quick, descending, dismissive cadential gesture.

In the chorus, “The people are the heroes now” – as the Chinese citizens gather on the stage, representing the airport runway, and await the arrival of President Nixon’s airplane – they declare: “When we look up, the fields are white/With harvest in the morning light/And mountain ranges one by one/Rise red beneath the harvest moon” (I/i/166–84). Americans commonly referred to the country as “Red China” (Wicker 1991, 576). This “red” depiction of the dawn provides an obvious political reference in the libretto, and the fields “white with harvest” suggest the fertile ground and symbolize the strong potential of the country.

LISTENING EXAMPLE: CD-1, t-3 (0:00–2:17)

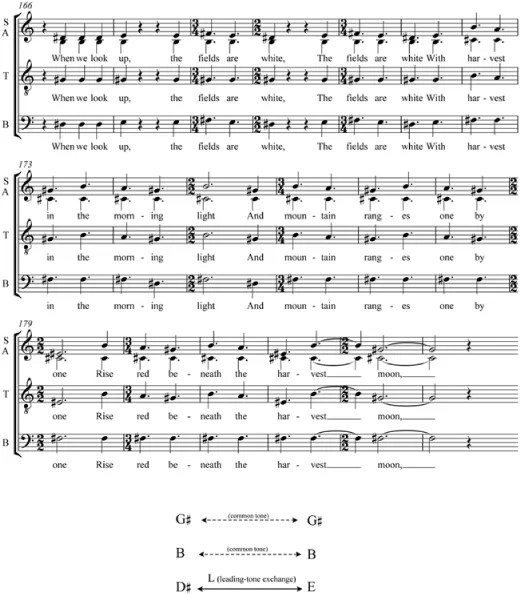

Just prior to this passage, in the refrain of the chorus, L transforms G# minor and E major triads into one another in a repetitive passage and in a parsimonious (or maximally smooth) way (I/i/162–5). As the citizens, in parallel motion in both the bass and soprano lines, begin to look up at the white fields, however, the addition of a nonchord tone, F#, begins to disrupt the harmonic repetition. This note stands in opposition to the D# bass of the G# minor triad as a diatonic inversion around E (I/i/166–71), as shown in the score of Example 1.3. In this way Adams preserves the parsimonious voice-leading of the L transformation, illustrated below the score, even as he begins to move away from his repetitive use of this transformation. As the passage continues, the pitch rises from the opening D#4 to B4 in the soprano line, contrasting sharply from the range of the refrain, where the sopranos span only a half step. Harmonically, Adams also moves away from the repetitive L transformation in the refrain by adding C#, which first appears as a nonchord tone in parallel fifths with the F# below it. However, instead of acting as nonchord tones, these two notes subsequently form a new F# minor triad, as the only remaining note from the initial chord, B, resolves down by step in a suspension figure to A to complete the triad (I/i/172). The motivic motion of a central note surrounded by diatonic steps in both directions continues, as before, but now diatonically inverted around a higher pitch, A4, in the soprano line, joining in the overall rise in tessitura.

Example 1.3 L transformations, nonchord tone activity, motion to F# minor (I/i/166–84)

As the citizens observe the mountain ranges beyond, the F# minor triad begins to dominate harmonically, and the inversional motivic pattern continues around A. Yet at the same time it begins to revolve around F# as well (I/i/177–84). Here, the lower set of notes is a step higher than before, centered around F# rather than E, and the motion around this central note occurs in the soprano and tenor lines, while the bass sustains a pedal point on the central note. In addition, the motivic pattern does not always occur in immediate succession, as before.

Through repetition, Adams links the citizens’ observations of the glorification of the people as the “heroes now” with white fields and mountains rising “red beneath the harvest moon.” The sheer imagery created by the libretto is vivid, but Adams intensifies the impact of the scene by returning to the opening repetitive L transformation, here a step higher enharmonically (I/i/185). The nonchord tone figures recur as before and begin to rise progressively, depicting both the mountains rising up and the citizens looking up through text painted by a substantial ascent in overall register in all of the voices, finally reaching an octave above the initial pitch, enharmonically, in the sopranos, from D#4 to E♭5 – an increase in register that is matched by the basses, an octave below; exceeded in the altos, B3 to D♭5; and nearly reached in the tenors, G#3 to F4 (I/i/162–204). Harmonically, more of the motivic figures described previously dominate the passage, centering mainly around the B♭ minor triad with which it begins. The passage ends on an incomplete Gø7 chord, missing its third, ironically the B♭ around which this passage centers harmonically.

This opening chorus concludes with a reprise of the refrain “The people are the heroes now/Behemoth pulls the peasant’s plow” (I/i/205–22). In addition to the return of the text, the initial L transformation between G# minor and E major returns to round out this second and final section of the opening chorus. In the section as a whole, Adams musically depicts the color and beauty of the landscape through the use of register and the use of the parsimonious L transformation, before the repetitive chord pattern breaks free to explore a richer harmonic palette and rises up in pitch. Finally, the unity created by the use of a single distinctive melodic motive, the L transformation, and a distinctively homorhythmic texture musically depicts the unity of the Chinese citizens in their appreciation of their rich land as red dawn breaks.

Richard and Pat Nixon, on the other hand, characterize the landscape quite differently. President Nixon quickly dismisses the landscape, based on his observations during his flight from Shanghai to the capital city of Peking. As noted in his memoirs:

We stopped briefly in Shanghai to take aboard Chinese Foreign Ministry officials and a Chinese navigator; an hour and a half later we prepared to land in Peking. I looked out the window. It was winter, and the countryside was drab and gray. The small towns and villages looked like pictures I had seen of towns in the Middle Ages. (Nixon [1975] 1990, 559)

The libretto represents this commentary literally in an aside remark to Chou, in which Nixon characterizes the landscape as “drab and grey” (I/i/476–86). Unlike the colorful and harmonically rich music that exemplifies the Chinese citizens’ view of the landscape, the music that sets Nixon’s dismissive attitude toward the landscape, and perhaps its people, stays firmly within its repetitive harmonic pattern. However, like the earlier choral passage, the primary harmonic transformations in the two depictions of the landscape are identical, L, here between an E minor and a C major triad. They are all, in fact, looking at the same landscape. The fact that each of the chords in this harmonic transformation is a major third away from the earlier pair, G# minor and E major, mirrors the major-third related harmonic relationship first presented in the orchestral introduction.

LISTENING EXAMPLE: CD-1, t-6 (1:53–2:09)

Pat Nixon brutally summarizes the Nixons’ view of the landscape in one wor...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Music Examples

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I SETTING THE SCENES

- PART II CHARACTERS AND MUSICAL CHARACTERIZATION

- PART III NATIONALISM AND CULTURAL DISTINCTION

- Bibliography

- Index