![]()

1 Thinking and theorizing about educational systems

In the beginning

This book is where the Morphogenetic Approach was first developed and presented in 1979. Revisiting it gives me the opportunity to repay some debts and also to re-endorse this explanatory framework by replying to some of its critics. Let me briefly revert to the theoretical landscape in which this approach to explaining the emergence of State educational systems was conceived. In the social sciences, those were the days of ‘the two sociologies’,1 when explanations based upon action and chains of interaction increasingly diverged from those that focused upon systems and culminated in the endorsement of systemic autopoiesis without actors. In the philosophy of social science these two sociologies were underwritten by Methodological Individualism and Methodological Holism, in which the ultimate constituents of the social world were respectively held to be ‘other people’ or ‘social facts’.2 Social Origins of Educational Systems should be seen as a howl of protest against this theoretical and philosophical background.

The original Introduction shows the importance I attached to resisting both of these types of approaches, ones I later critiqued as ‘upward conflationism’ and ‘downward conflationism’.3 The following quotation set the terms of the theoretical challenge to which the whole book was the response:

It is important never to lose sight of the fact that the complex theories we develop to account for education and educational change are theories about the educational activities of people … [However] our theories will be about the educational activities of people even though they will not explain educational development strictly in terms of people alone.4

This is a statement about the need to acknowledge, to tackle and to combine agency and structure rather than conflating them. It was made difficult in two ways. On the one hand, there was no existing stratified social ontology that justified different emergent properties and powers pertaining to different strata of social reality, being irreducible to lower strata and having the capacity to exercise causal powers. Instead, notions of ‘emergence’ and of their causal powers5 met with resistance and the charge of reification.

However, the properties and powers of State educational systems are considered here to be both real and different from those pertaining to educational actors – even though deriving from them. The problem was twofold: how to justify the existence of both sets of properties and how to theorize their interplay. The articulation of a stratified social ontology for the social order was the achievement of Roy Bhaskar’s Possibility of Naturalism, also published in 1979.6 Retrospectively, the concurrence of our two books was advantageous because although Bhaskar’s social ontology would have provided a more robust basis than the ‘sheepish’ Methodological Collectivism7 upon which I perforce relied in this study, its absence at the time induced me to develop a thoroughgoing explanatory framework for analysing the interplay of structure and agency. This was the first appearance of the Morphogenetic Approach, which I view as the ‘methodological complement’8 of the Critical Realist ontology that developed simultaneously.

On the other hand, in 1979 the landscape tilted again with the publication of Anthony Giddens’ Central Problems in Social Theory.9 Its key claim that ‘structure is both medium and outcome of the reproduction of practices’10 was the most blatant statement in the English-speaking world that the ‘problem of structure and agency’ should be ‘transcended’ by treating the two components as interdependent and inseparable. In other words, ‘central conflation’ had arrived and purported both to nullify Bhaskar’s stratified social ontology and to render my morphogenetic approach redundant. I will not recapitulate my criticisms of structuration theory, made from 1982 onwards,11 which basically held it guilty of sinking the differences between structure and agency rather than linking them. In turn, Bhaskar adopted this critique of Giddens12 and critical realists generally came to accept that different emergent properties and powers are proper to different levels of social organization, and that those pertaining to structure are distinct and irreducible to those belonging to agents. Thus, it follows that critical realism is necessarily ontologically and methodologically opposed to ‘transcending’ the difference between structure and agency. Instead, the name of the game remains how to conceptualize the interplay between them, which is what the morphogenetic approach set out to do from the beginning.

Philosophical underlabouring and forging an explanatory toolkit

When taken together, two theorists enabled the ‘morphogenetic approach’ to be advanced in 1979. What it aimed to do was to develop a framework for giving an account of the existence of particular structures at particular times and in particular places. The phenomenon to be explained was how State educational systems (SES) came into existence at all and, more specifically, why some were decentralized (as in England) whilst others were centralized (as in France) and what consequences resulted from these differences in relational organization. Thus, the ‘morphogenetic approach’ first set out to explain where such forms of social organization came from – that is, how emergents in fact emerged.

Thanks to David Lockwood’s seminal distinction between ‘system’ and ‘social’ integration,13 it was possible to conceive of the two (taken to refer to ‘structure’ and ‘agency’) as exerting different kinds of causal powers – ones that varied independently from one another and were factually distinguishable over time – despite the lack of a well-articulated social ontology. Thanks to Walter Buckley, my attention was drawn to ‘morphogenesis’: that is, ‘to those processes which tend to elaborate or change a system’s given form, structure or state’,14 in contrast to ‘morphostasis’, which refers to those processes in a complex system that tend to preserve the above unchanged. However, Buckley himself regarded ‘structure’ as ‘an abstract construct, not something distinct from the on-going interactive process but rather a temporary, accommodative representation of it at any one time’,15 thus tending to ‘dodge questions of social ontology’.16

Although the study is ontologically bold in advancing the relational organization of different structures of educational systems as being temporally prior to, relatively autonomous from and exerting irreducible causal powers over relevant agents, there was something less courageous in acceeding with the Methodological Collectivists (Gellner and Mandelbaum) that such claims must be open to ‘potential reduction’ because their justification rested only on ‘explanatory emergence’.17 A more robust social ontology of causal powers and generative mechanisms was needed to underpin this explanatory programme and allow it to shed its apologetic attitude. This is what Bhaskar provided in The Possibility of Naturalism, describing his own role as ‘underlabouring’ for the social sciences.

Nevertheless, his realist social ontology does not explain why, in Weber’s words, given social matters are ‘so, rather than otherwise’. A social ontology explains nothing and does not attempt to do so; its task is to define and justify the terms and the form in which explanations can properly be cast. Similarly, the Morphogenetic Approach also explains nothing; it is an explanatory framework that has to be filled in by those using it as a toolkit with which to work on a specific issue, who then do purport to explain something. Substantive theories alone give accounts of how particular components of the social order originated and came to stand in given relationships to one another. The explanatory framework is intended to be a very practical toolkit, not a ‘sensitization device’ (as ‘structuration theory’ was eventually admitted to be); one that enables researchers to advance accounts of social change by specifying the ‘when’, ‘how’ and ‘where’ and avoiding the vagaries of assuming ‘anytime’, ‘anyhow’ and ‘anywhere’.18

In this book I am doing two jobs at once: developing the toolkit and also putting it to work to offer an explanation of the social origins of State educational systems and of the difference that their relational organization makes to subsequent processes and patterns of educational change. Part I of the book uses this framework to account for the diachronic development of State educational systems and their differences in structural organization, which can be summarized as centralized or decentralized. Part II moves on to explain the synchronic effects of emergent centralization and decentralization, whilst ever these two forms of relational organization were maintained. The briefest outline of this explanatory framework is needed before turning to some of the debates it has provoked.

The origins of the morphogenetic approach

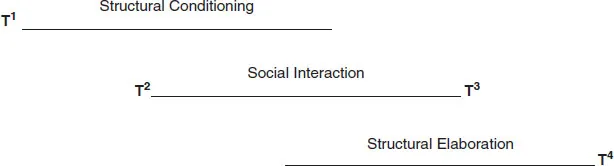

Although all structural properties found in any society are continuously activity-dependent, analytical dualism allows ‘structure’ and ‘agency’19 to be separated and their interplay examined in order to account for the structuring and restructuring of the social order or its component institutions. This is possible for two reasons. Firstly, ‘structure’ and ‘agency’ are different kinds of emergent entities,20 as is shown by the differences in their properties and powers, despite the fact that they are crucial for each other’s formation, continuation and development. Thus, an educational system can be ‘centralized’ whilst a person cannot, and humans are ‘emotional’, which cannot be the case for structures. Secondly, and fundamental to how this explanatory framework works, ‘structure’ and ‘agency’ operate diachronically over different time periods because: (i) structure necessarily pre-dates the action(s) that transform it and (ii) structural elaboration necessarily post-dates those actions, as represented in Figure 1.1.

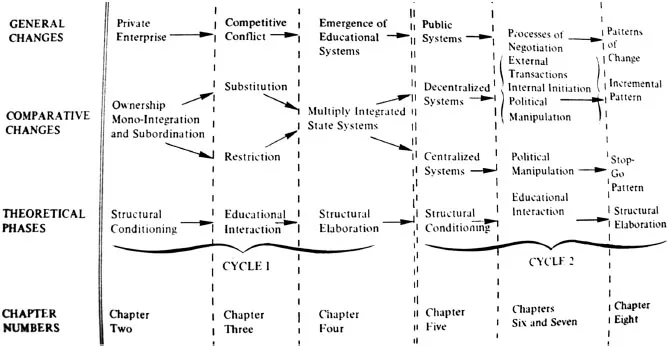

It aims to make structural change tractable to investigation by breaking up the temporal flow – which is anything but ‘liquidity’ – into three sequential phases: <Structural Conditioning → Social Interaction → Structural Elaboration>. This carves out one morphogenetic cycle, but projection of the lines forwards and backwards connects up with anterior and posterior cycles. Two such cycles are analysed in the current study: the one prior to the emergence of State educational systems and the one posterior to them (the book ends with the state of educational affairs in 1975). The delineation of Cycle I and II followed the preliminary judgement that the advent of a State system represented a new emergent entity, whose distinctive relational properties and powers conditioned subsequent educational interaction (processes and patterns of change) in completely different ways compared with the previous cycle, in which educational control derived from private ownership of educational resources. The establishment of such morphogenetic ‘breaks’ – signalling the end of one cycle and constituting the beginning of the next – is always the business of any particular investigator and the problem in hand.

Figure 1.2 illustrates how the explanatory framework is used throughout the book and should disabuse the prevalent mistaken view that the morphogenetic approach dated from 1995.21

Figure 1.1 The basic morphogenetic sequence.

Figure 1.2 Summary use of the Morphogenetic Approach in the book.

Why study State educational systems and how?

This is merely a particular version of the question ‘Why study social institutions at all?’ Some social theorists do not,22 and substitute the investigation of ‘practices’, ‘transactions’, ‘networks’, ‘activities’ and so forth. Those doing so find themselves driven to introduce a ‘qualifier’ whose job is to register that these doings are not free-floating but are anchored temporally and spatially, the most common being the term ‘situated’. However, to talk, for example, about ‘situated practices’ may seem to give due acknowledgement to the historical and geographical contextualization of doings such as ‘transactions’ but only serves to locate them by furnishing the co-ordinates of their when or where. Simply to provide these spatial and temporal co-ordinates is not to recognize the fact that all actions are contextualized in the strong sense that the context shapes the action and therefore is a necessary component in the explanation of any actions whatsoever, since there is no such thing as non-contextualized action (contra Dépelteau).23

Thus, the point is how this context should be conceptualized. Some attempt a minimalist response and basically construe the situated ...