![]()

Part I

Housing Outside City Walls: New Forms of Sovereignty in Late Ottoman Palestine

![]()

Chapter 1

Empire Land Commodification and the Backlash of Nationalism

This book is about the history of nationalism in Israel-Palestine, presented as a history of national housing, and like most attempts to study ‘the history of ’ conflicted presents it starts at ‘the beginning’. The beginning in question has been greatly debated, since identifying a starting point is a strong historiographic act, framing research questions and identifying objects of inquiry. Yet my purpose here is not to intervene in the historiography of Israel-Palestine by challenging periodization and starting points (while my project does that). Instead, I am interested in how a focus on housing as object of inquiry shifts our perception of history. What can an architectural history focusing on national housing tell us about Israel-Palestine history?

In this chapter I employ homeland as a lens through which to observe the emergence of nationalism as an idea, political tool, and concrete dwelling space. What I mean by this is that I will be using housing as a tool to slice back layers of history and conceptions of historiography in order to identify moments of pivotal change in the political fabric of Ottoman Palestine in relation to its built environment. Though housing and settlement have been accepted as key tools in Zionist nation building during British Mandate and State periods, I will show that not only was proto-national housing already a major new phenomenon in the Late Ottoman period, but also that Ottoman Imperial rule itself was responsible for inculcating proto-national housing and settlement by Jews and local peasants alike.

New dwelling spaces responded to the Ottoman 1858 land commodification code which completely transformed the relationship between people and land across the Empire (Shafir, 1996b). Reforms permitted individuals to possess large areas of land and develop it as plantations and real-estate ventures, pushing many of the fellaheen or peasants out of their homes and villages. Non-Muslims were given legal access to land for the first time, including Western colonial interests aiming to replace the Ottoman Empire, and Zionists interested in national settlement. In this chapter I identify new dwelling forms in response to these consequences as ‘the beginning’ of proto-nationalism, the fall of Empire, and the opening of national struggle over Israel-Palestine as homeland.

This chapter engages a growing body of literature that works to add complexity to the origin stories of Zionism and Palestinian nationalism by debating its ‘year zero’ (Cohen 2015; Morris, 1987; Khalidi, 1991; Pappé, 1994). My study expands this debate by asking what is the ‘ground zero’ for this process, namely not only when, but primarily where and by what architectural settlement form did this conflict over homeland begin.

Interrogating the basic assumptions underlying the historiography of Israel-Palestine via the architectural history of habitation and occupation of the land, I engage with two theoretical bodies of literature which interrogate each other: postcolonial theory, primarily Frantz Fanon’s work on agrarian reform as central to the postcolonial project of nationalism, understood as restructuring society after dispossession by colonialism and imperialism (Fanon, 1961); and Karl Polanyi’s Marxist political-economic theory of extreme-nationalism as a response to social destruction caused by subjecting the ‘three non-commodifiable goods’ of land, labour and money to the market (Polanyi, 2001).

Ultimately, this chapter argues that nationalism appeared in Late Ottoman Palestine as an attempt to re-embed land, labour and money in society in response to Ottoman commodification. My argument revisits Zionist historiography’s ‘beginning’ as housing ‘stepping outside’ Ottoman city walls, and challenges the myths and assumptions that it was a singular Jewish-national phenomenon.

This chapter takes readers through four realms by which 1858 land reforms produced this new built environment: changes to land ownership and acquisition; transformations to landed labour and the rights it entails to land/homeland/village; introduction of financial institutions mediating the relationship between people and land; and subjection of citizenship and sovereignty to the market. I then analyse the architecture of newly produced built environments as people’s attempts to reverse the destruction of society by commodification of land, labour, money and sovereignty and to restore it using the framework of nationalism.

A Housing 'Big-Bang'

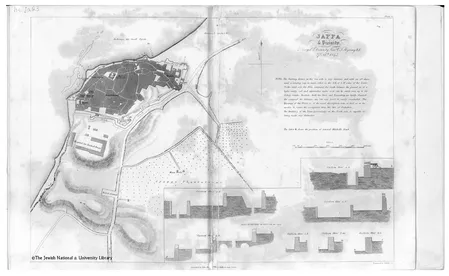

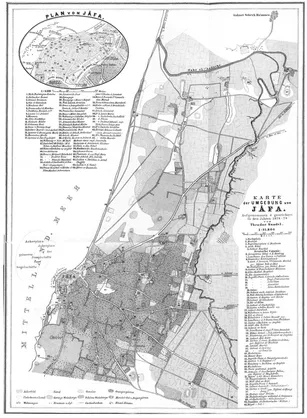

Examining the built environment of Late Ottoman Palestine, one cannot ignore a sudden, dramatic change in the landscape between the 1860s and 1890s.1 In the course of some 35 years this walled-city built environment, stable for some four centuries of Ottoman rule, was irrevocably transformed into a non-fortified landscape of ex-urban neighbourhoods and plantation villages. One clear example is the city of Jaffa and its surroundings. Documented in 1842 as a fortified city set in arid surroundings (figure 1.1), by 1879 its walls had been taken down and the previously barren, dangerous surrounding landscape cultivated by vast agricultural plantations dotted with small mud hut villages and later with urban neighbourhoods (figure 1.2) (Kark, 1990).2

Pre-transformation, city and village alike were ‘built with defense in mind like forts

Figure 1.1. Jaffa and Environs, 1842. (Source: Skyring, Charles Francis, London, 1843; courtesy of the Jewish National & University Library, Jerusalem)

Figure 1.2. Theodor Sandel map of the Jaffa area, 1878– 1879. (Source: By courtesy of Or Alexandrowicz)

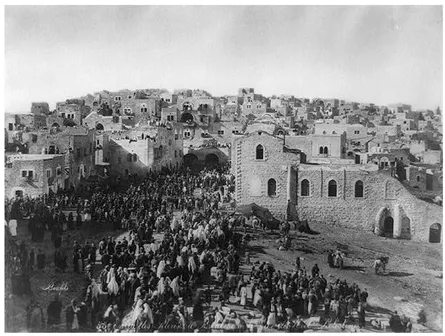

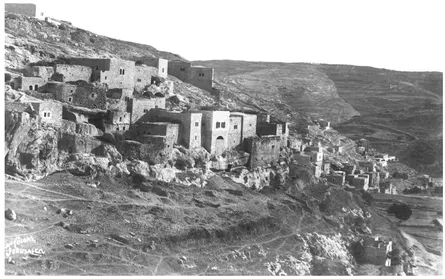

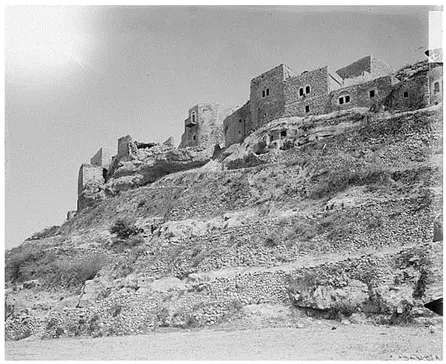

and close together … houses of a small village just as closely packed as the buildings in a city so that a village will look like a fragment knocked off a city’ (Grant, 1921 [1907], pp. 43–44). Photographs of cities and villages from that time, for example the city of Bethlehem and village of Silwan, confirm Grant’s observation of ‘the village as a fragment of a city’ – that is to say, that city and village built environments differed primarily in scale, while embodying the same structural conception, both built on hillside, their houses forming tight, parallel, wall-like façades along the topographic lines (Grant, 1921 [1907]).

The continuous and tightly clustered houses form an environment where no single house is disconnected from the community. While houses in Bethlehem have two to three storeys and houses in Silwan have one to two storeys, both settlements are composed of permanent structures built of stone, with shallow vaulted roofs serving as a continuous rooftop streetscape used for defence. This compactness of hillside stone-built structures ‘became a fashion in times of insecurity, when feuds between villages led to raids and reprisals’ (Grant, ibid.). Insecurity served the Ottomans as a means to govern their vast Empire while employing a minimal governing mechanism. Actively-produced chaos, pitting villages against each other and encouraging nomad raids, prevented the consolidation of any local power able to challenge Ottoman sovereignty (Gerber, 1987, 1986; Lees, 1905; Finn, 1923; Reilly, 1981, Twain, 1959; Kark, 1986) (figures 1.3 and 1.4).

Figure 1.3. Bethlehem c. 1875. (Source: Library of Congress; photo: Felix Bonfils)

Figure 1.4a. Silwan village by Jerusalem, 1890. (Source: Princeton University Library; photo: Felix Bonfils)

Figure 1.4b. Unidentified village in Palestine c. 1900. (Source: Library of Congress, LC-DIG-matpc-10543; photo: American Coloby)

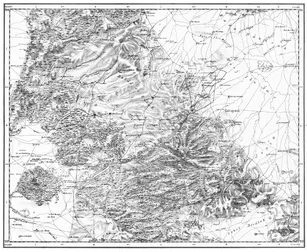

The Survey of Western Palestine, conducted by Conder et al. between 1870 and 1877, documents the built environment of Palestine prior to its dramatic transformation by providing detailed mapping of the location, size and composition of villages and towns. Conder et al. (1888) identify the vast majority of settlements in Ottoman Palestine as fortified hill villages, mapping very few villages in the newly available flatlands. Comparing plates mapping the Carmel coast with the Samaria hills indicates that in 1870 the hills of Judea and Samaria were heavily populated compared with the plains and the coast (figure 1.5a and b). In terms of the built environment, Ottoman Palestine can be understood as one of walled cities, even though the majority of the people were peasants living in villages (Gerber, 1986; Reilly, 1981).

Figure 1.5a, b. Survey of Western Palestine Plates 7,8, Carmel Shore and Upper Samaria hills. (Source: by courtesy of the Jewish National & University Library, Jerusalem)

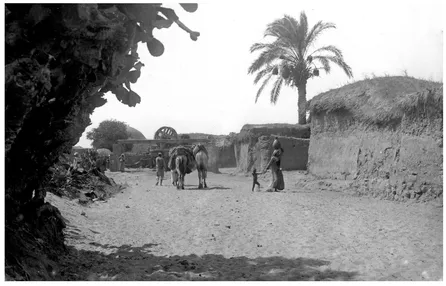

Starting in the 1860s, however, a distinctly new built environment developed in Palestine’s plains, characterized by campus clusters of freestanding structures in agricultural plantations or urban neighbourhoods. The Survey of Western Palestine had identified 261 Arab-Palestinian villages in the same territory that became Israel in 1948 (i.e. excluding the West Bank and Gaza). Khalidi identifies 418 Palestinian villages evacuated by their inhabitants in the 1948 war, based on the British survey of 1944–1945 (Khalidi, 1991, 1992; Kadman, 2009). To these we should add the 137 Arab-Palestinian settlements within Israel, mapped by the Arab Centre for Alternative Planning, none of which were formed after 1948 (Khamaisi, 2004). These give a total of 555 active and populated Palestinian settlements before the 1948 war, namely indicating that 294 new Palestinian villages were formed in these 68 years. These new villages were predominantly plantation villages, the product of the Ottoman land commodification.

Figure 1.6. Typical village north of Jaffa c. 1920. Note Russian Compound (top left) and Mishkenot (bottom left). (Source: Central Zionist Archive; photo: Jacob Ben-Dov)

This distinctly new built environment involved changes to building materials and construction techniques – from cut stone structures built by professional masons to mud-brick and concrete-brick houses built by dwellers themselves (figure 1.6):

An examination of the material used in construction shows that most Palestinian houses are of two types: those of stone and those of clay. The first occur principally in the mountainous parts of the country where stone is abundant. In the Mediterranean plain and the Jordan depression, where stone is relatively scarce and difficult to transport, clay bricks were and are still used. (Canaan, 1933, p. 8)

How was the rigid Ottoman built environment and governing mechanism transformed so radically to form unfortified campus landscapes, and why?

Scholars agree that this transformation resulted from complete reconstruction of the Ottoman land system by the 1858 Land Code, part of a series of Tanzimat (literally ‘reorganization’) reforms over the period 1839–1876 in an attempt to modernize the Empire and reverse its slow decline in comparison to European powers (Kark, 1990; Gerber 1986). The 1858 Land Code regarded land, for the first time in the Ottoman framework, as a commodity to be exchanged monetarily. Coupled with the introduction of a banking system, the first paper banknotes (1856) and a deed system disconnecting land ownership from land cultivation, the new code enabled ownership of vast plots of land by absentee owners for the purpose of for-profit agriculture and real-estate profiteering (Gerber, 1986; Reilly, 1981). Social processes, including corruption and distrust of the Ottoman authorities, led to such results as registration of whole villages under one owner and dismantling Musha collective landownership, causing dispossession of significant numbers of fellaheen from their right to land. This population, as well as landless immigrants, was employed as disposable wage labour in vast new plantations formed by Muslim, Christian, Jewish and Bahai landlords, generating a great sense of injustice and various attempts to restore relationship to place (Issawi, 1966; Kark, 1986; Aaronson, 1990; Kark and Aaronson, 1988; Ben-Arzi, 1988; Katz, 1984b), elaborated in Chapter 3.

Land Reform and the Commodific...